by Bethany Augliere Friday, October 12, 2018

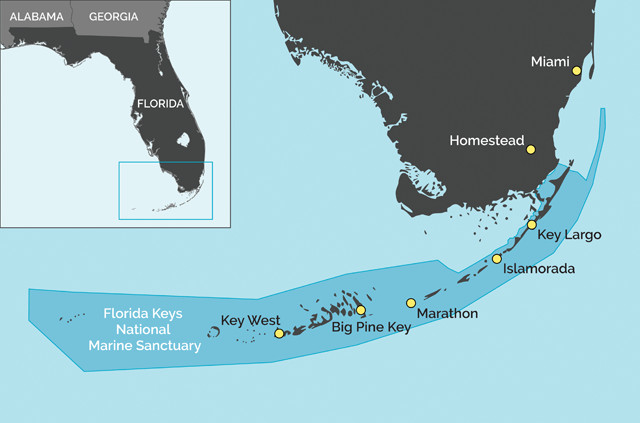

Designated in November 1990, the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary protects nearly 10,000 square kilometers of ocean surrounding the islands, including North America's only barrier reef. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

Off the tip of the Florida Peninsula lies the world’s third-largest living coral reef, the Great Florida Reef. The only barrier reef system in North America, it is composed of a system of individual reefs that together extend 270 kilometers south of Miami through the Florida Keys, a crescent-shaped chain of more than 1,500 islands, about 30 of which are inhabited. This ecological treasure is home to more than 6,000 species of marine life, including colorful fish and endangered sea turtles, as well as extensive seagrass beds, mangrove islands and about 1,000 shipwrecks.

On Nov. 16, 1990, amid mounting human-caused threats to the reef’s well-being, President George H.W. Bush officially recognized the reef’s value to Florida’s marine ecosystem — and to the state’s economy — establishing the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. The marine sanctuary — the country’s second, and one of 15 marine protected areas in the National Marine Sanctuary System — protects nearly 10,000 square kilometers of waters surrounding the Keys, including coral reefs, seagrass meadows, mangroves, sand flats and “hardbottom” seafloor habitats.

The reefs of the Florida Keys face several threats, including pollution and warming water temperatures, which can make corals, like this diseased brain coral, susceptible to bleaching events. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

In 1872, the U.S. established its first national park: roughly 9,000-square-kilometer Yellowstone. The first marine equivalent wasn’t established for more than another century, following a series of environmental protections put in place during the early 1970s, including the Endangered Species Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, and the Coastal Zone Management Act.

The first national marine sanctuary, Monitor National Marine Sanctuary off the coast of North Carolina, was established in 1975, after researchers discovered the wreckage of the USS Monitor, the United States’ first iron-clad warship, built during the Civil War. The Monitor’s discovery prompted North Carolina Gov. James E. Holshouser Jr. to nominate the final resting place of the war vessel for national marine sanctuary status, recognizing its importance in maritime history and the need to protect it from further damage.

The crescent-shaped island chain of the Florida Keys (western end shown here) extends south of Miami to Key West, spanning 240 kilometers. Credit: NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS and U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team.

Since then, the national marine sanctuary system has grown considerably. It now includes 13 marine sanctuaries and two national monuments, totaling 1.5 million square kilometers of marine and Great Lakes waters, ranging from the Florida Keys to American Samoa. In 2015, President Barack Obama added two new marine sanctuaries, one off the coast of Maryland and the other in Lake Michigan, which were the first protected marine areas designated by the federal government in 15 years. Sanctuaries require protective measures that place limits on human activity, including commercial fishing, shipping traffic and recreational use.

In the 1950s, growing threats to the Florida Keys reef’s health, such as overfishing and seagrass die-offs, began alarming scientists and conservationists. This led to legislative action at the state level, including the creation of America’s first underwater park, John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park in Key Largo. Later, in 1975 and 1981, two small national marine sanctuaries were designated, Key Largo National Marine Sanctuary and Looe Key National Marine Sanctuary, respectively.

On Aug. 4, 1984, the M/V Wellwood, a cargo ship carrying chicken feed, ran aground on the reef near Key Largo, damaging 75,000 square meters of reef habitat and 5,800 square meters of living coral. Also visible in this photo is the classic "spur and groove" reef formation, with high ridges of coral separated by sand channels. Credit: NOAA/Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

Despite designating these protected areas, the reef still faced trouble. In 1983, for example, periods of weak winds and high air temperatures caused ocean warming and widespread coral bleaching on the reef along the southernmost islands of the Florida Keys. Bleaching events along with seagrass die-offs continued into the late 1980s. In 1987, amid the ongoing decline in reef health, the Department of the Interior approved oil and gas development off the Florida coast, which began in late 1988.

Also, in the late 1980s, three large merchant vessels ran aground on the reef, damaging the sensitive coral. One ship, the M/V Wellwood, a cargo ship carrying chicken feed, damaged 75,000 square meters of reef habitat and 5,800 square meters of living coral off Key Largo. Restoration of that area continues today.

Eventually, the combined threats prompted Congress to act, passing the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and Protection Act. And, on Nov. 16, 1990, President Bush formally established the sanctuary, which incorporated both the Key Largo and Looe Key sanctuaries.

Within the boundaries of the sanctuary, visitors can fish, snorkel and scuba dive. However, there are rules and regulations to protect the reef and other marine life. For instance, in all areas of the sanctuary, visitors cannot move, remove, injure, break or possess coral or live rock. Boaters are not allowed to anchor on the coral reefs in less than 12 meters of water, and public mooring balls anchored to the seafloor that boaters can tie up to are in place at certain sites to reduce anchor damage. Furthermore, no dredging or drilling is allowed. To regulate fishing, the sanctuary uses a strategy of marine zoning in which no fishing is allowed in parts of the area, while size and catch limits, established by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, are in place in other areas.

The economy of the Keys is driven by tourism and recreational activities, such as boating. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

Fiishing and diving are allowed within the sanctuary with certain restrictions. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

The Florida Keys island chain is geologically young and predominantly made of limestone. About 125,000 years ago, water levels were roughly 30 meters higher. The Upper Keys, from Bahia Honda Key north, are remnants of an ancient reef that existed during this time, while the Lower Keys formed later from old sandbars.

During the last ice age, starting about 100,000 years ago, sea levels dropped, exposing the reef and sandbars, which lithified into the rock that makes up the islands today. The rock underlying the Upper Keys is mainly Pleistocene-aged Key Largo Limestone. This white and light gray limestone is characterized by coral heads in a calcarenitic matrix — limestone composed of more than 50 percent detrital, sand-sized carbonate grains. The formation is very porous and permeable, and as such, is part of the Biscayne Aquifer, a shallow aquifer that provides South Florida with much of its freshwater.

In the Lower Keys, the exposed bedrock is the Miami Limestone, also Pleistocene-aged but younger than the Key Largo Limestone. Additionally, rather than being composed of lithified corals, this limestone is mainly made of ooids — spherical, millimeter-scale grains that form as carbonate minerals precipitate around existing shell fragments or sand grains — along with some quartz and mollusk fossils.

The current living barrier reef is about 5,000 to 7,000 years old and lies about 9.5 kilometers seaward of the Florida Keys in waters ranging from 4 to 9 meters deep. The reef exhibits what’s known as a “spur and groove” formation, with coralline ridges and channels perpendicular to the shoreline, shaped, in part, by wave energy. There are about 50 types of coral that make up the reef — such as sea fans, brain coral, star coral and the critically endangered staghorn coral — which together represent about 80 percent of all coral reef species in the Tropical Western Atlantic.

Scientists have also documented more than 500 species of fish that call the Great Florida Reef home. One common fish family along the reef is parrotfish, which are characterized by bright colors and a bird-like beak that helps the fish scrape algae, their food source, off coral. In doing so, parrotfish also contribute sand to the beaches of the Florida Keys. As the fish scrape algae from the coral, they also ingest bits of the coral’s calcium carbonate skeleton, which they later expel undigested. One large parrotfish can release up to a ton of sand each year.

A Spanish hogfish swims near a reef in Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Credit: NOAA/Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

The turquoise waters and vibrant reefs of the Florida Keys bring in about $2.7 billion a year, from snorkelers, divers, fishermen, boaters and other tourists. And 3.5 million people visit the area each year, supporting 54 percent of all jobs there, according to Monroe County, which includes the Keys. Nearly everything in the Florida Keys is linked to the health of the reef — and the reef is struggling.

Decades of overfishing, disease, pollution and coastal development, as well as introductions of invasive species, have caused a prolonged decline in reef health. In the last 240 years, reef coverage on the seafloor has declined by 54 percent, according to a 2017 study that used historical nautical maps to determine the changes. Nearshore reefs — those at the 4-meter depth contour — experienced the largest decline, with a loss of 87.5 percent of reef coverage.

In 2014 and 2015, the Great Florida Reef experienced back-to-back major bleaching events because of warmer-than-average sea-surface temperatures, triggered by a strong El Niño. Then, in 2015 and 2016, the corals experienced back-to-back disease outbreaks. Additionally, a disease known as “white plague,” first discovered in 2014 off the port of Miami, has spread north and south, including into the Florida Keys. Overall, it has impacted half of the Great Florida Reef, as of a 2017 assessment.

Around the world, from the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of northeastern Australia to the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef off Central and South America, climate change is considered the greatest threat to coral reef health. Increasing temperatures lead to coral bleaching and disease outbreaks. Stronger and more frequent storms destroy reef structure while ocean acidification due to increasing atmospheric and oceanic carbon dioxide levels makes it difficult for young coral polyps, as well as other vital reef organisms that make shells, like snails and crabs, to build their calcium carbonate skeletons.

The dour trends in the health of reefs worldwide, including the Great Florida Reef, bode ill for both marine ecology and local and regional economies. But there is hope. As vulnerable as reef systems are to climate change impacts, they are also dynamic and sometimes resilient ecosystems. In some places around the world, new coral growth has been observed in as little as two years after bleaching events. And scientists, nonprofit organizations like the Coral Restoration Foundation, and others are also working to restore reefs in the Florida Keys and elsewhere by growing coral in captivity and reintroducing it in the wild. Whether these efforts will be enough to reinvigorate the reef system remains to be seen.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.