by Mary Caperton Morton Thursday, May 24, 2018

Bahia Honda Key in Florida. Credit: ©Shutterstock.com/fotomak

The Florida Keys are one of the most ephemeral places on Earth. The majority of the planet’s landmasses are millions of years old, but these islands have only been around for a few thousand years. Already, rising sea levels are threatening to submerge the young archipelago, possibly within the next century.

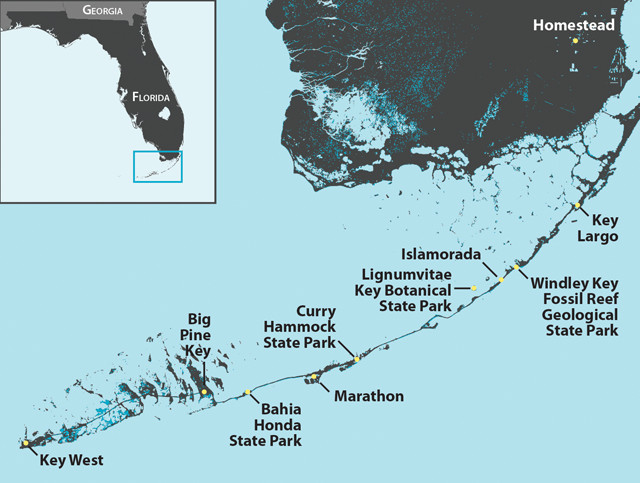

Today there are 882 charted Key islands, 30 of which are inhabited. The 204-kilometer-long Overseas Highway, a concrete marvel of civil engineering built in the 1930s, connects the island arc from Key Largo in the northeast to Key West in the southwest. A drive down this aptly named wave-top-skimming road is a great way to tour the Keys’ unique coral geology, tropical ecology and island-life culture.

The Keys Are Born

During the Pleistocene, the barrier islands and ancient reefs now known as the Florida Keys lay beneath the warm, nutrient-poor waters off North America’s southern coast. Over thousands of years, a 60-meter-thick layer of sand and limestone accumulated on the seafloor. Once this undersea carbonate mountain grew high enough to reach sunlight, corals began colonizing the peaks.

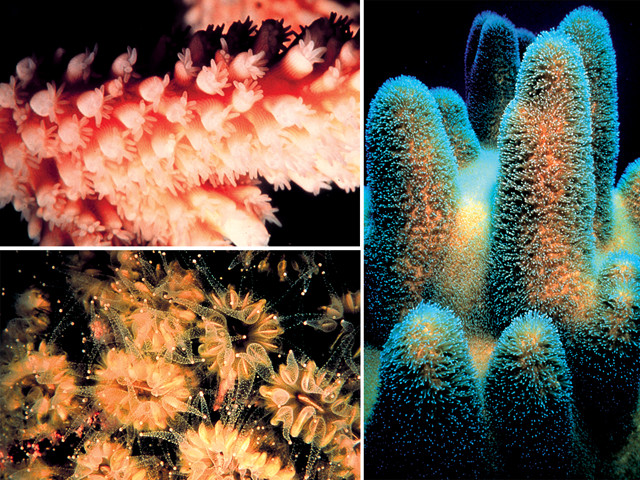

As colonial corals grow, they secrete calcium carbonate skeletons to encase their soft living polyps. The polyps share their limestone home with single-celled algae called zooxanthellae, which produce food for the polyps through photosynthesis, supplying up to 90 percent of a coral’s nutrients. This symbiotic relationship enables the coral to thrive in warm, nutrient-poor waters and, over time, build immense reefs that support oases of biodiversity in otherwise barren oceans.

The Keys' ancient coral reefs were built mainly by elkhorn, staghorn, brain and star corals. They flourished for millions of years until about 100,000 years ago, when Earth's climate cooled and the polar ice caps began to expand, lowering sea levels and exposing the corals. Credit: NOAA, Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

The Keys’ ancient coral reefs, built mainly by elkhorn, staghorn, brain and star corals, flourished for millions of years until about 100,000 years ago, when Earth’s climate entered a period of cooling and the polar ice caps began to expand. As the ice sheets grew, they locked up water from the oceans, lowering sea levels by as much as 100 meters and exposing much of southern Florida and the Keys.

The island chain is thought to have been inhabited as early as 10,000 years ago, based on North American migration studies, but the earliest evidence of habitation — old trash heaps called middens found on Key Largo — dates to just 1,300 years ago. A huge man-made mound of coral rock, known as the Key Largo Temple Mound, thought to have been abandoned about A.D. 1200, and a similarly dated burial mound on Lignumvitae Key are two of a handful of archaeological sites left by early inhabitants. By the time the islands were first charted by Juan Ponce de Leon in 1513, originally dubbed “Los Martires,” or “the Martyrs,” they were inhabited by the Calusa and Tequesta tribes.

The Keys didn’t attract much attention from the mainland until 1821, when Florida was ceded by Spain to the United States, whereupon Key West became an important military outpost guarding the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico. Situated between the Gulf and the Atlantic, Key West grew into a center of trade. Some islanders also made a fortune “shipwrecking” — gathering goods and valuables from the many ships that wrecked on the reefs. Completion of the Overseas Railway in 1912, and the Overseas Highway in 1938, made for easy access to and from the mainland.

Driving the Overseas Highway

Traditionally, the Keys are divided into the Upper Keys, from Bahia Honda northward, and the Lower Keys, from Big Pine to Key West. Starting from the Florida mainland, the northernmost island considered a “Key” — an island built on an ancient coral reef formation as opposed to sand — is Elliott Key in Biscayne National Park.

Regardless of technicalities, Key Largo bills itself as the Gateway to the Keys. The town itself is home to some unique diversions like the Caribbean Shipwreck Museum and dolphin encounters at Dolphins Plus, Inc., and the Theater of the Sea.

Key Largo’s most famous entertainment, however, is offshore: Some of the world’s best scuba diving and snorkeling can be found on the reefs a few kilometers east of the island, along the Great Florida Reef, the only living coral barrier reef in the continental U.S. and the third-largest barrier reef in the world. The densest and most spectacular sections of the 270-kilometer-long Great Florida Reef are east of Key Largo.

Molasses Reef, French Reef and the Grecian Rocks are three popular dive sites, and Spiegel Grove features a 155-meter-long U.S. Navy ship — intentionally sunk in 2002 to form an artificial reef — that now hosts a spectacular diversity of organisms. Dozens of diving guides can be found in Key Largo: Horizon Divers, Ocean Divers and It’s a Dive are three reputable companies. If diving all day isn’t enough for you, check out the Key Largo Undersea Park, where you can stay underwater all night in a submarine hotel room.

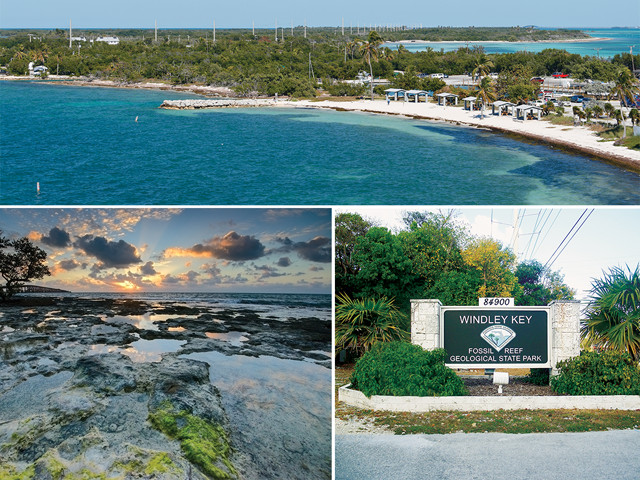

Heading south from Key Largo on the Overseas Highway, you cross numerous bridges and pass by a handful of uninhabited mangrove islands. Mangroves are the great colonizers and protectors of the Keys as the salt-tolerant plants greatly reduce storm surges from tropical storms and hurricanes. Storm surges are especially destructive in the low-lying Keys, where the highest point in the chain, on Windley Key — home of the Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park — is a mere 5.5 meters above sea level. Most of the islands lie less than 2 meters above the waves.

Credit: Clockwise from top: ©iStockphoto.com/ideeone; Mary Caperton Morton; ©iStockphoto.com/Jeremy Sterk

Top and bottom left: From Bahia Honda north is considered the Upper Keys, which sit atop an ancient exposed coral reef, called Key Largo Limestone. Right: Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park is the highest point on the keys, but is just 5.5 meters above sea level.

The Keys mark the northernmost extent of many tropical species not found anywhere else in the United States, including the American crocodile (not to be confused with the American alligator found on mainland Florida), the Key Largo woodrat and the miniature Key deer, which stands about 75 centimeters tall. The Key lime tree is another native, and Key lime pie was originally concocted in these islands.

Heading farther south, you soon come to Islamorada, which bills itself as the “Village of Islands.” Stop at Robbie’s for lunch, and after you eat, buy a bucket of baitfish and head down to the docks to feed the resident tarpon. As many as a hundred of these massive 3-meter-long sport fish gather at Robbie’s docks everyday looking for handouts. Toss a baitfish into the water or, if you’re really brave, dangle a fish out over the water to see the tarpon jump.

The Islamorada area is home to six state parks, two of which — Long Key State Park and Curry Hammock State Park — allow camping. If you’re looking for a spot to swim, keep driving south to Bahia Honda State Park, home to one of the world’s most beautiful tropical beaches. Bahia Honda also allows camping, but reservations are often booked months in advance.

About 50 kilometers on from Islamorada, in Marathon, you’ll pass one of the Keys’ two airports. If you need to stop for food, gas or a restroom break, do it here because once you leave Marathon, you’ll be suspended over the ocean on concrete pylons for a little while, as you traverse the famed Seven Mile Bridge.

When it was built in 1936, the Seven Mile Bridge connecting Knights Key (home of Marathon) to Little Duck Key was one of the longest bridges in the world. The scenery from the bridge is some of the best in the Keys: With the Atlantic Ocean on one side and the Gulf of Mexico on the other, the expanse of sea and sky is broken only by the narrow highway, tiny wild-mangrove islands and the occasional boat.

The bridge marks the boundary between the Upper Keys and the Lower Keys, a boundary also defined by a distinctive change in geology. While the Upper Keys sit atop the ancient exposed coral reef, called Key Largo Limestone, the Lower Keys are composed of oolitic Miami Limestone. Over time, as the Upper Keys’ limestone and coral slowly eroded back into the shallow sea, calcium carbonate slowly precipitated from the seawater onto shell fragments to form pebble-sized spheres called ooids. The ooids were then deposited onto the deeper, coral-free limestone bedrock and lithified over time into the oolites that make up the Lower Keys.

Key West: Where Eccentricity Is an Art Form

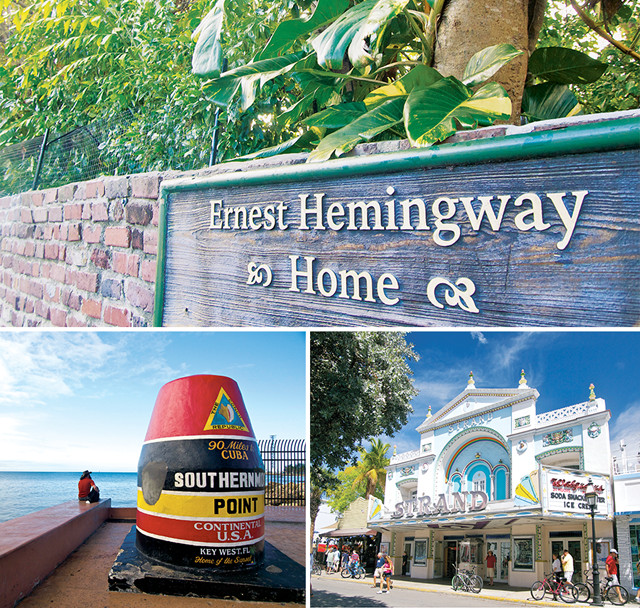

Key West is the southernmost city in the contiguous United States and, aside from uninhabited Marquesas Keys and Dry Tortugas, it is the last Key. Home to more than 30 percent of the Keys’ 80,000 residents, it’s also the most populous. The island’s most famous denizen was probably Ernest Hemingway, who owned a home there for 30 years. Every summer Key West hosts a Hemingway festival for three days, ending on the author’s birthday, July 21. The Papa Hemingway Look-Alike Contest is the biggest event, drawing more than 150 white-bearded contestants. Hemingway’s house on Duval Street is now a museum overrun with dozens of descendants of the writer’s favorite polydactyl, or six-toed, cat, Snowball.

Other attractions on Key West include: the “Southernmost Point in the Continental U.S.A.” (the southernmost point in the whole U.S. is on the Big Island of Hawaii); the ethereal Key West Butterfly and Nature Conservatory; the educational Florida Keys Eco-Discovery Center; as well as a lighthouse museum, an aquarium, a shipwreck museum and a thriving waterfront.

One of the most popular activities on Islamorada is feeding the resident tarpon at Robbie's. As many as a hundred of these massive 3-meter-long sportfish gather at Robbie's docks looking for handouts. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton

Hosting hundreds of thousands of visitors each year on just 15 square kilometers of land, Key West can be a crowded place, but you don’t visit the Keys to stay on the islands. You visit the Keys to get out on the water: rent a kayak, charter a fishing boat, ride a jet ski, go sailing, board a yacht or embark on a cruise ship. Or get in the water: The Keys are a prime destination for swimming, snorkeling and scuba diving. Ferries also run daily, weather permitting, to Dry Tortugas National Park, home of the 19th-century coastal fortress, Fort Jefferson, and known for bird watching, snorkeling and scuba diving. Considered one of the most remote and pristine parks in the United States, the uninhabited island lies 113 kilometers offshore and is accessible only by boat.

Sea Changes

Key West is the most tourist-oriented part of the Keys. Popular spots include the former home of Ernest Hemingway (now a museum), the shops on Duval Street and the Southernmost Point marker. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton

Top left: ©DanielSchwen, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported; rest: Mary Caperton Morton

Sea levels have been rising for thousands of years, since the end of the last glacial maximum, by an average of about 60 centimeters every thousand years. But the rate has sped up in the last 100 years, rising 15 centimeters since 1913, according to tide gauges in Key West monitored by scientists and the U.S. Navy.

In 2007, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projected that sea levels would rise 18 to 59 centimeters by 2100. Other studies have suggested even more dramatic rise, but according to the nonprofit Nature Conservancy, even a conservative sea-level rise estimate of 18 centimeters would mean the loss of about 24,000 of the Keys’ 62,000 hectares of land.

The Florida Keys are composed of 882 islands, all below 5.5 meters elevation. A 1-meter rise in sea levels would submerge all the areas shown in teal. Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI

Given the ephemeral nature of the Florida Keys, a visit to the islands should be at the top of every island-lover’s wish list.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.