by Mary Caperton Morton Wednesday, October 18, 2017

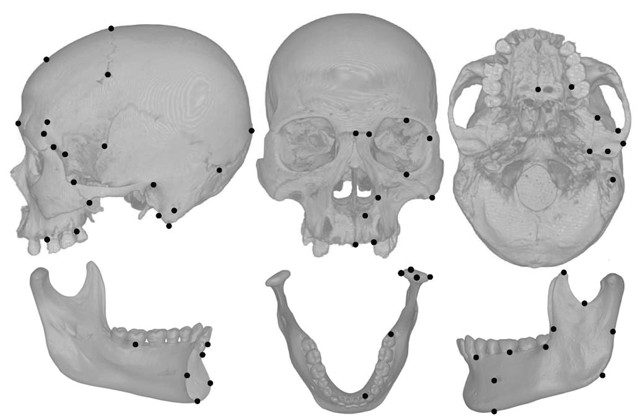

Researchers used points, or landmarks, on numerous crania and mandibles from a variety of preindustrial farming and foraging populations to compare features of post-agricultural skulls. Credit: David Katz and Tim Weaver, UC Davis.

The dawn of agriculture left an indelible mark on early human societies, and a new study finds that eating softer, cultivated foods subtly changed the shape of human skulls. Scientists have long suspected that the transition from hunting and foraging to farming and raising livestock would have affected our skulls, specifically the mandible and other anatomy involved in chewing, but quantifying such changes has proven difficult.

David Katz of the University of California, Davis, and colleagues, analyzed the shapes of 559 crania and 534 mandibles from more than two dozen preindustrial farming and foraging communities from around the world. These communities included, for example, soybean farmers from Japan’s 17th-century Edo period, 4,000-year-old Neolithic dairy farmers in Europe, and Paleolithic hunter-gatherers in Africa from roughly 12,000 B.C. Comparing the skulls of farmers to those of foragers, and drawing upon previously published skull studies as well, the team found statistically significant differences in the skulls from the distinct populations. They also found that the effect of agriculture on skull shape was more pronounced in the dairy-focused populations, which consumed the softest foods, compared to the cereals-based groups.

The finding supports the “masticatory-functional hypothesis,” which was first proposed in 1977 to explain differences in the shapes of skulls from Mesolithic hunter-gatherer populations and later agriculturalists. Available evidence suggests “the idea that softer agricultural foods reduce [chewing] demands, resulting in less robust craniofacial skeletons and reduced and repositioned chewing muscles,” the team wrote in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.