by Mary Caperton Morton Friday, May 13, 2016

Team member Neil Puckett of Texas A&M University surfaces from the dive excavation in Florida with a 14,550-year-old limb bone from a juvenile mastodon. Credit: Brendan Fenerty.

Following the discovery of stone tool artifacts uncovered near Clovis, N.M., in 1932, archaeologists have thought that the people who made the tools — named the Clovis people — were the first to populate the Americas, about 13,500 years ago. But evidence has been mounting for cultures even older than the Clovis, with archaeological sites and artifacts older than 14,000 years found as far south as Chile and genetic evidence dating the first incursions into North America to about 15,000 years ago. Now, a new study reporting on an underwater archaeological excavation at a site in Florida that dates to 14,550 years ago is adding more evidence of pre-Clovis people, and shedding light on how they may have spread across the Americas.

Co-principal investigator Jessi Halligan examines a mastodon bone brought up by Puckett. Credit: Brendan Fenerty, courtesy of CSFA.

In the early 1980s, buried at the bottom of the Aucilla River in northern Florida, researchers found a mastodon that had been butchered next to a small pond. Dating efforts at the time revealed the mastodon to be at least 14,400 years old. That was “an impossible age for the scientific community to accept at the time,” said Jessi Halligan, an archaeologist at Florida State University and lead author of the new study, published today in Science Advances, in a press conference. Because of the initial skepticism and the difficulties of underwater excavations, the Aucilla River site, dubbed the Page-Ladson site, was all but forgotten.

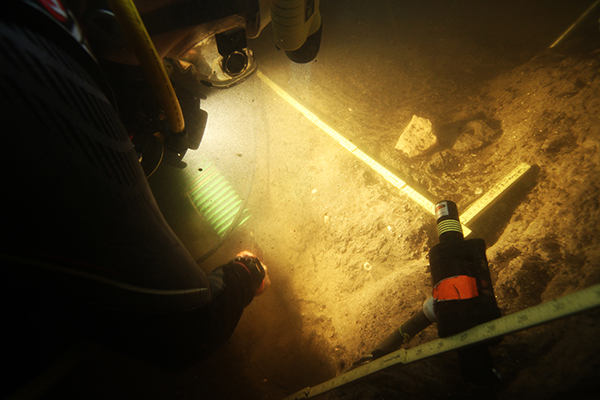

In 2012, a team led by Halligan and Mike Waters of Texas A&M University began re-excavating the site using state-of-the-art underwater excavation methods. Sealed within undisturbed geological deposits, they found stone tools, a knife and stone tool flakes associated with mastodon remains, including a tusk with knife marks that were consistent with butchering. Whether the mastodon was killed or scavenged is unknown, said co-investigator Daniel Fisher of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor at the press conference.

Researchers working on the 14,550-year-old site at the bottom of the Aucilla River. Credit: S. Joy, courtesy of CSFA.

The discovery helps paint a picture of a small band of nomadic people hunting or scavenging for large game along a series of sinkholes in the area of what is now the Aucilla River. A jawbone and teeth from a canine may also indicate that the band coexisted with dogs, though further work will be needed to confirm that find, the researchers said.

This biface stone tool was found alongside the mastodon remains at the bottom of the Aucilla River. Credit: Jessi Halligan.

The knife found at the site is bifacial and does not bear any resemblance to the famously fluted Clovis points thought to have tipped spears or other projectiles, Waters said at the press conference. “One of the biggest questions to address,” Waters noted, is: “When did this technology eventually morph into Clovis and why? How was the technology developed?”

Co-principal investigator Michael Waters (right) and team member Morgan Smith examine the biface after it is excavated. Credit: A. Burke, courtesy of CSFA.

New radiocarbon dating of the stone tools and particles of mastodon dung indicate that the Page-Ladson site, at 14,550 years old, is the oldest radiocarbon-dated site in the Southeast and one of the oldest sites in North America. “The evidence from this site is a major leap forward in shaping a new view of the peopling of the Americas at the end of the last ice age,” Waters said. The site “provides unequivocal evidence of human occupation that predates Clovis by [more than] 1,500 years and contributes significantly to the debate over the timing and complexity of the peopling of the Americas.”

This mastodon tusk was recovered from the site. Credit: Daniel Fisher, University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology.

The dating of the Page-Ladson site is contemporaneous with other archaeological sites found in Oregon, Texas and Wisconsin, as well as sites in South America, suggesting that pre-Clovis people were widespread throughout the Americas by 14,500 years ago, Waters said. “In the archaeological community, there is still a terrific amount of resistance to the idea that people were here before the Clovis,” he said. “The beauty of the Page-Ladson site is that it provides everything that people would want to see: excellent dating and clear artifacts in a solid geological context.”

Even with the site, pre-Clovis evidence remains rare, the researchers said. “The rarity of these early sites is due to low population densities resulting in few archaeological sites, and low site visibility due to deep burial; and in some cases such as this, the evidence is submerged.”

The excavation at Page-Ladson highlights the importance of underwater archaeological techniques in finding pre-Clovis sites, many of which may have been submerged by rising sea levels and changing river courses, the researchers said. However, finding people and funding to do the work is challenging, Halligan said. “There are probably fewer than 10 people in the U.S. who are specialists in prehistoric archaeology [and] who have the ability to work underwater,” Halligan said.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.