by Sara E. Pratt Thursday, March 29, 2012

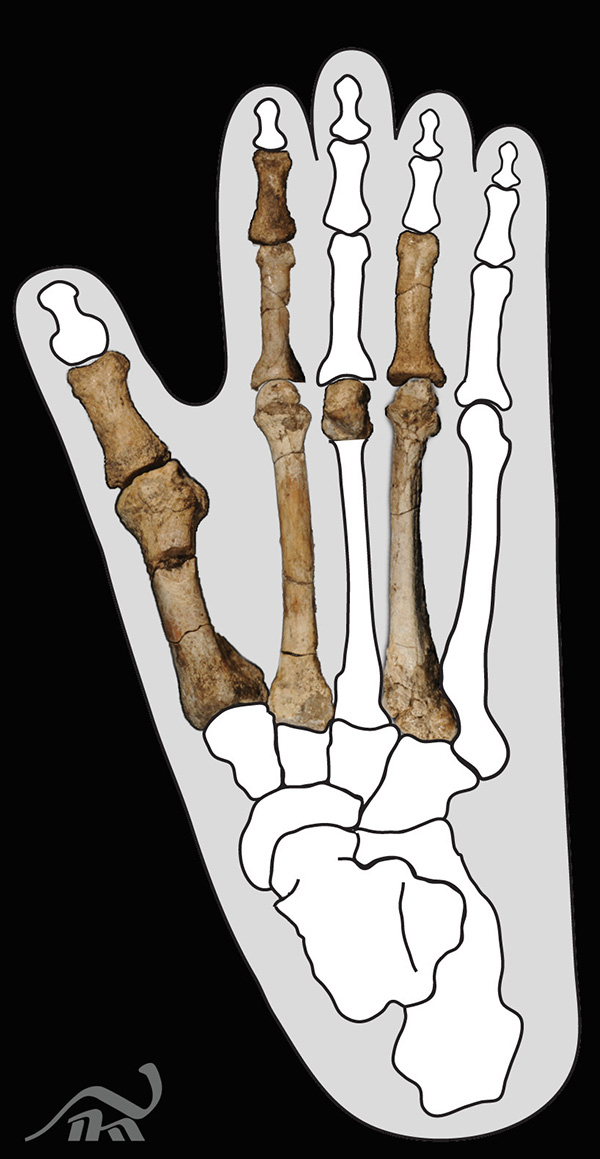

The Burtele partial foot superimposed on an outline of a gorilla foot. © The Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Photo courtesy: Yohannes Haile-Selassie

When Lucy and other Australopithecines were walking around Ethiopia 3.4 million years ago, they may have encountered another hominin species that still climbed trees and also walked, but with a gait more like an ape than their bipedal neighbors. The tantalizing new discovery of a few fossil foot bones shows that at least one species retained an opposable big toe, one million years after the grasping feature was thought to have disappeared. The discovery means that two different types of locomotion co-existed during early human evolution, which sheds new light on the evolution of bipedalism and may warrant the naming of a new hominin species.

Several million years ago, humans stopped climbing trees and started walking on two feet. Today, they are the only mammal that does so, making bipedalism one of the defining characteristic of humans. But the evolution of bipedalism didn’t follow a singular path. Since hominins diverged from chimpanzees 6 million years ago, the foot has gone through a lot of adaptations. Around 4.4 million years ago, Ardipithecus ramidus had feet adapted for both walking and climbing trees with an opposable big toe, like a chimpanzee and, therefore, probably walked more like a chimp than a modern human. More recent hominins including Australopithecus sediba, Australopithecus africanus, Homo habilis and Homo floresiensis, had a more complete arch than Ardipithecus ramidus and their big toes were more in line with the other toes, but their feet were not yet completely modern and retained some adaptations for living in trees. Homo erectus was likely the first hominin to have truly modern foot, with a full arch and all five toes aligned.

The eight foot bones were discovered in Burtele, Ethiopia, in 2009, by Stanford University graduate student Stephanie Melillo, who saw the bones poking out of a rock above a volcanic tuff that has been radiometrically dated. The depositional environment indicates the area was wooded, unlike the Awash Valley in the Afar Depression where Lucy was discovered in 1974.

An Ardithipecus-type species of this age that was capable of both climbing and walking upright, albeit awkwardly like an ape, could be a new species — but more fossils will need to be found, reported Yohannes Haile-Selassie, curator and head of physical anthropology at The Cleveland Museum of Natural History, and colleagues in Nature.

“Now, of course, what we want to know is what does the skull look like? What do the teeth look like?” said co-author Bruce Latimer, Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. The joint features are different enough to suspect they come from a previously unidentified species. “Is it within the range of variation of other fossils?" Latimer said. "I don’t think so. But until we find more evidence we’re being cautious about it.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.