by Mary Caperton Morton Thursday, May 24, 2018

Eastern Wyoming is known for its wide open spaces. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton

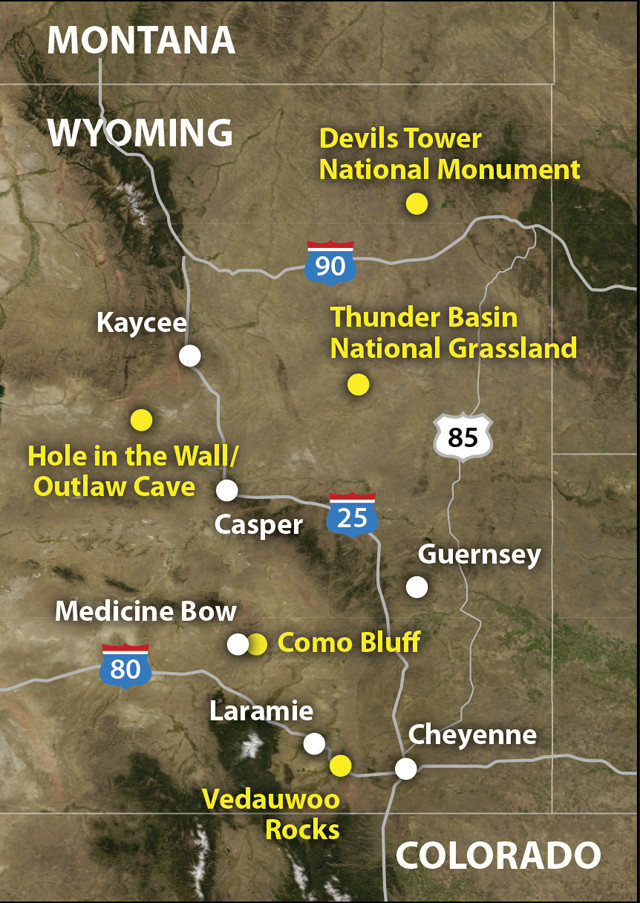

When vacationers plan trips to Wyoming, the western half of the state, with its grizzly bears, Grand Tetons and Yellowstone National Park, tends to be the biggest draw. But Eastern Wyoming — home to bone wars, outlaw hideouts and the nation’s first national monument — also boasts a captivating mix of Wild West history and geologic marvels.

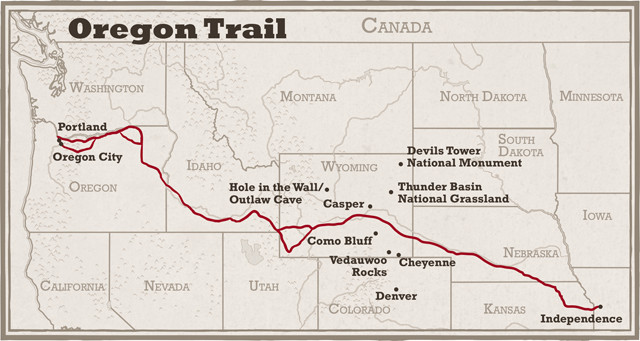

Hundreds of thousands of emigrants made their way from Independence, Mo., to Oregon City, Ore., just outside of Portland, along the Oregon Trail, which ran through southeastern Wyoming. In many parts of Eastern Wyoming, the landscape is largely unchanged since those days. A driving loop around this part of the state, from Cheyenne through Casper, up to Devils Tower and then back south through Thunder Basin National Grassland makes a nice road trip. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton

Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI

Many of the highlights can be found along a scenic 1,200-kilometer driving loop that starts in the southeast corner of the state, rolls through rugged mountains and wide-open basins up to Devils Tower in the northeast corner, and then returns south through Thunder Basin National Grassland where modern-day road trippers cross the well-rutted paths of the pioneers.

Crack Climbing at Vedauwoo Rocks

Between Cheyenne and Laramie in the southeast corner of Wyoming juts a jumbled mountain of granite boulders known as Vedauwoo Rocks. Reminiscent of Southern California’s Joshua Tree boulders, Vedauwoo (pronounced ve-DA-voo) — from the Arapaho word meaning “born from the earth” — is a fitting description for these ancient intrusive rocks.

Vedauwoo’s boulders are made of 1.4-billion-year-old Sherman granite, which intruded during the Precambrian and was brought to the surface about 70 million years ago during the uplift of the nearby Laramie Mountains. Over time, the hard granite, glittering with large crystals of quartz, orthoclase, plagioclase and mica, has been sculpted into big, rounded boulders and free-standing hoodoos, often split by parallel cracks that have made Vedauwoo a world-class rock climbing destination.

Looking south from Vedauwoo Rocks on a clear day, you can see the snowy white peaks of Colorado's Front Range. Vedauwoo is located just off I-80, near Curt Gowdy State Park, which offers boating, mountain biking and camping. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton

Vedauwoo, which boasts more than 900 mapped climbing routes, is known for its array of off-width cracks: gaps wider than a hand but narrower than a body, which are notoriously difficult and dangerous to climb, requiring climbers to painfully jam their fingers, hands, feet and sometimes their entire bodies into the cracks. Ascending off-width routes often requires a rare combination of skill, high pain tolerance, the flexibility of a contortionist and sheer strength, with “crack masters” routinely contorting themselves into awkward and uncomfortable positions in their quest to ascend the rock.

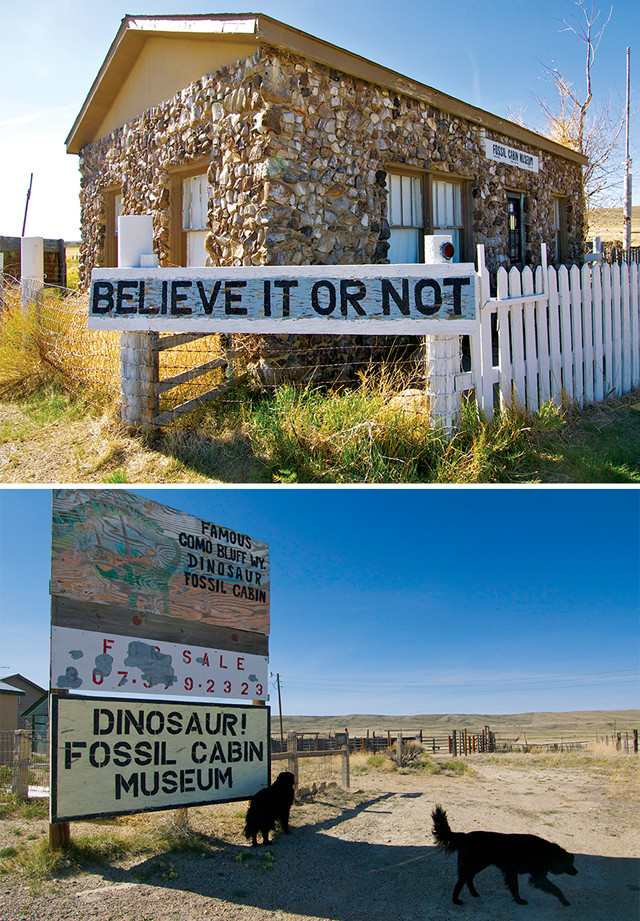

The Fossil Cabin at Como Bluff, built from more than 26,000 Jurassic fossils, has been closed and for sale since the mid-1990s. Como Bluff can be seen in the background. Credit: Mary Caperton Morto

Even if you’re not a crack climber, Vedauwoo has plenty to offer. Hiking trails thread through the rocks and wildlife abounds along aspen-lined, beaver-dammed creeks. The five-kilometer Turtle Rock trail, which departs from the Vedauwoo campground, is a great place to start exploring. Vedauwoo also attracts mountain bikers and anglers in the summer and cross-country skiers in the winter. The campground is a fee site, but the rest of the park is open to free dispersed camping, provided users practice “Leave No Trace” ethics. Curt Gowdy State Park, just east of Vedauwoo, also offers boating, fishing and swimming as well as a larger, more developed campground.

Como Bluff Bone Wars

Heading north from Laramie toward Medicine Bow, U.S. Highway 30/287 soon passes a must-see site for every dinosaur lover: a cabin built from more than 26,000 Jurassic fossils. Built in 1933, the Fossil Cabin at Como Bluff was dubbed “the Oldest Cabin in the World” by Ripley’s Believe It Or Not. The former museum is now shuttered and a large billboard advertises it for sale. Still, you can park and admire the outside of the cabin and catch a glimpse of Como Bluff, the fossil-rich ridge that was once a battleground in one of paleontology’s fiercest rivalries.

In 1877, when the Transcontinental Railroad was being built across Wyoming, two Union Pacific Railroad workers wrote a letter to Othniel Charles Marsh, a paleontologist at the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale, detailing their discovery of a trove of massive bones along Como Bluff. Marsh dispatched one of his students to the site to confirm the finds and the student reported both good and bad news: The fossils were spectacular and plentiful, but Marsh’s rival, Edward Drinker Cope of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, was already on the scene.

As two of the most preeminent paleontologists of their day, Marsh and Cope had already developed an abiding enmity, with each accusing the other of unprofessionalism and underhanded tactics in their quest to uncover and identify dinosaur fossils across the country. At the remote fossil-rich Como Bluff, relations between the two men came to a head, with their respective teams destroying fossils, dynamiting excavation pits, and seeding each other’s digs with odd, unrelated bones to delay and discredit the other’s work.

Top: The geography of the Hole in the Wall area is ideal for a hideout. Impenetrable red cliffs leave only a few passages from the east, and the west is guarded by the steep and deep Powder River canyons. Bottom: Around the turn of the last century, the steep and rugged Powder River canyons served as outlaw hideouts for notorious characters such as Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid and the Wild Bunch Gang. To find Outlaw Cave, visitors have to trek down into the canyon and follow the river downstream on the narrow trail pictured here. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton

Despite the squabbling, Como Bluff was a tremendously productive site, producing more than 100 tons of dinosaur, reptile, mammal, fish and amphibian fossils, most of which were shipped east by rail. Many of the most familiar dinosaur species have been uncovered here, including Allosaurus, Stegosaurus, Camarasaurus and Apatosaurus.

Today, the site is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and has been designated a National Natural Landmark. It is closed to the public, but a few active digs are still ongoing.

Hole in the Wall and Outlaw Cave

Continuing north from Medicine Bow on U.S. Route 487 will head you toward the aptly named area of Hole in the Wall, Wyo., which is about as rural as this country gets. Long dirt roads lead on forever, with few signs to guide the way. Back in Wyoming’s Wild West days, this place was even wilder: Around the turn of the last century, the steep and rugged Powder River canyons served as outlaw hideouts for the likes of Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid and the Wild Bunch Gang.

The geography of the Hole in the Wall area, just west of Kaycee, Wyo., and north of Casper, is ideal for a hideout: Impenetrable red cliffs leave only a few passages from the east, and the west is guarded by the steep and deep Powder River canyons. Outlaws could graze stolen horses and cattle in the verdant valley and retreat into the canyons if lawmen appeared on the horizon.

Outlaw Cave is on BLM lands, so travelers are free to visit. But like a good outlaw hideout, it remains tricky to find and hard to reach. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton

Much of the Hole in the Wall area is now privately owned by the Willow Creek Ranch, which offers trail rides and cowboy vacations, but a few pockets are still held by the Bureau of Land Management, including Outlaw Cave. Outlaw Cave is one of the only hideouts still standing — most of the cabins and corrals are long gone — but like a good outlaw hideout, it remains tricky to find and hard to reach (see sidebar, page <OV>).

Devilish Geology at Bear Lodge

Looming over Wyoming’s relatively flat northeastern plains, Devils Tower has served as a navigational and spiritual landmark for Native American tribes and travelers for thousands of years.

Long before it was dubbed Devils Tower National Monument in 1906, the nearly 1,600-meter-tall sentinel was known by various tribes as the Bear’s Lodge, the Bear’s Tipi, Tree Rock and Grizzly Bear Lodge (see sidebar). The name Devils Tower is considered an affront by many of the Native American tribes who revere the tower, including the Lakota, Crow, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Kiowa and Shoshone, among others, but the most recent proposal to rename the tower Bear Lodge National Historic Landmark was shot down in 2005.

The geologic story of Devils Tower is also a matter of contention. Geologists generally agree that about 40 million years ago, magma was forced up through the softer surrounding layers of Mesozoic sandstone and gypsum, which have since eroded away, exposing the tower seen today. But the nature of the intrusion and whether the magma breached the surface before it cooled have long been debated.

Depending on whom you ask, Devils Tower could be a stock, a laccolith, or a volcanic plug. A stock is a small intrusive magma body that cools underground, without erupting to the surface. A laccolith is a term reserved for a mass of igneous rock that intrudes between layers of other rocks, pushing them up to create a dome at the surface. And volcanic plugs form in the necks of volcanoes; as the outer layers of the mount erode away, the vertical plug is exposed.

Unfortunately, the evidence needed to distinguish among the three scenarios has been lost to erosion in the 40 million years since the intrusion took place, leaving the origin of Devils Tower a geologic mystery. Little volcanic material is found in the area of the tower, though pyroclastic flows from the same time period as the intrusion have been found farther afield in Wyoming, Montana and South Dakota.

Native Americans have long called Devils Tower by other names, including the Bear's Lodge, the Bear's Tipi, Tree Rock and Grizzly Bear Lodge. It is still considered sacred and offerings are frequently left there. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton

Erosion is still at work on the plains around the Tower and on the Tower itself. The powerful Belle Fourche River flows nearby, and freeze and thaw cycles continuously work on the cracks between the tower’s vertical columns, occasionally breaking off chunks, which litter the base of the tower.

Devils Tower’s dramatic and distinctive hexagonal columns are made up of phonolite porphyry, a hard gray rock with visible feldspar crystals that makes for excellent rock climbing. The Tower was first climbed in 1893 by two Wyoming ranchers who built a ladder up to the summit by driving wooden pegs into a crack between the columns. Less than 1 percent of the National Monument’s half-million annual visitors come to climb the Tower, but most of those who do ascend it by the classic Durrance Route, which attacks the tower up a distinctively leaning dihedral column and is considered only moderately difficult by climbers.

Permits (free) are required in order to climb Devils Tower. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton

Climbing of the Tower is considered a desecration by many Native Americans, who still regularly visit the Tower to conduct ceremonies and leave offerings. Starting in 1995, the park service attempted a compromise by asking climbers to adhere to a voluntary climbing ban in the month of June, when traditional summer solstice ceremonies are held at the Tower. Climbing permits issued show that about 85 percent of climbers honor the moratorium.

Following in Pioneer Footsteps

Thousands of wagon wheels cut ruts in the soft rock in Eastern Wyoming as pioneers made their way across the country on the Oregon Trail. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton

Running south from Devils Tower, U.S. Highway 85 skirts the edge of the Thunder Basin National Grassland. The rolling prairie looks like classic Oregon Trail country, and sure enough, the banks of the North Platte River were once a superhighway for pioneers traveling west on the Oregon Trail.

Near Guernsey, the meter-deep ruts cut into the soft white sandstone by passing wagon wheels give some sense of the sheer number of wagon parties that passed through this area on their way west between 1841 and 1869. Some pioneers also carved their names into the nearby Register Cliff, where a Pony Express Station later stood. Today the ruts, cliffs and Pony Express site are all preserved as a state historic site managed by Guernsey State Park.

Eastern Wyoming is often overshadowed by the more famous attractions in the west, but it’s certainly worthy of vacation time, especially for history and geology buffs. Driving 1,200 kilometers may seem like a task, but take at least a week to savor the scenic loop and by the time you cross paths with the pioneers, you’ll have a whole new appreciation for Wyoming’s Wild East.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.