by Terri Cook and Lon Abbott Thursday, May 24, 2018

Western Nebraska's rock monuments, rising above the Great Plains, have significant historical, cultural and scientific value. Credit: Kahvc7s

Western Nebraska does not usually appear on lists of travel destinations, yet this region has a historical and cultural significance as vast as its landscape. For more than 500,000 westbound pioneers who tenaciously crossed the continent along the Oregon, California and Mormon trails, this region — where the flat plains give way to a rugged terrain of sculpted badlands and rocky bluffs — heralded their arrival in the West.

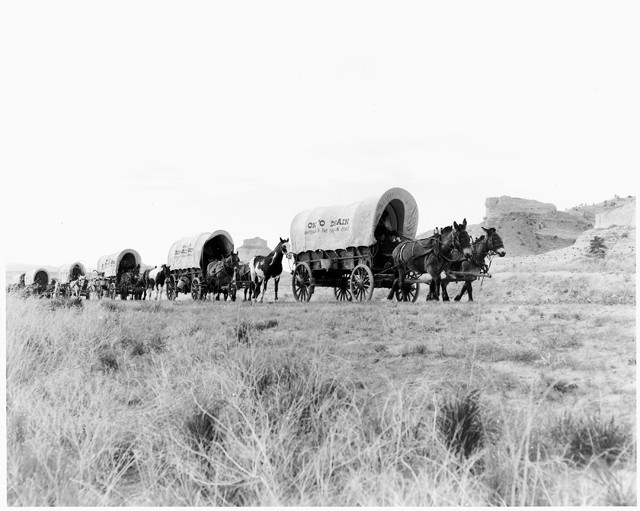

When the pioneers reached what is now the Nebraskan panhandle, they had already toiled for eight hard weeks from Independence, Mo., the preferred jumping-off point in the 1840s, traversing the vast Great Plains. They hungered for a tangible indication that they had made progress on their journey: In the panhandle, they glimpsed the first stone monuments rising above the grasslands — Courthouse Rock, then Chimney Rock, and finally, Scotts Bluff signaled that one-third of the trek to Oregon now lay behind them.

For more than 500,000 westbound pioneers who crossed the continent along the Oregon Trail, as well as the California and Mormon trails, Western Nebraska — where the flat plains give way to a rugged terrain of sculpted badlands and rocky bluffs — heralded their arrival in the West. Credit: National Archives and Records Administration

All three are now geoheritage sites, geological features with significant scientific, cultural, educational or historical value. Western Nebraska’s rock monuments were milestones on the trail west, but they also have significant scientific value. From the 1830s to the turn of the century, the attention of geologists and paleontologists, like that of the rest of the nation, was riveted on the West; the fossil discoveries in western Nebraska are some of the most significant mammal sites ever found in the U.S. The Nebraska skeletons displayed in premier natural history museums around the country paint a picture of an American Serengeti teeming with vast animal herds that roamed Nebraska between 33 million and 19 million years ago.

Like travelers of old, modern visitors still seek out western Nebraska’s geoheritage sites — and the panhandle’s natural beauty and solitude — for the insights they provide into our nation’s westward migrations, the construction of our continent’s interior, and the evolution of mammals.

The High Plains

Western Nebraska occupies the eastern flank of the huge, flat plateau known as the High Plains, the westernmost and highest part of the Great Plains, which stretch from South Dakota to the Texas panhandle. The High Plains consist of a thick pile of sedimentary rock overlying a deeply buried igneous and metamorphic base. Inundation by a series of shallow seas between 540 million and 70 million years ago deposited 2.4 kilometers of limestone, shale and sandstone before the last sea drained away in the Early Paleogene.

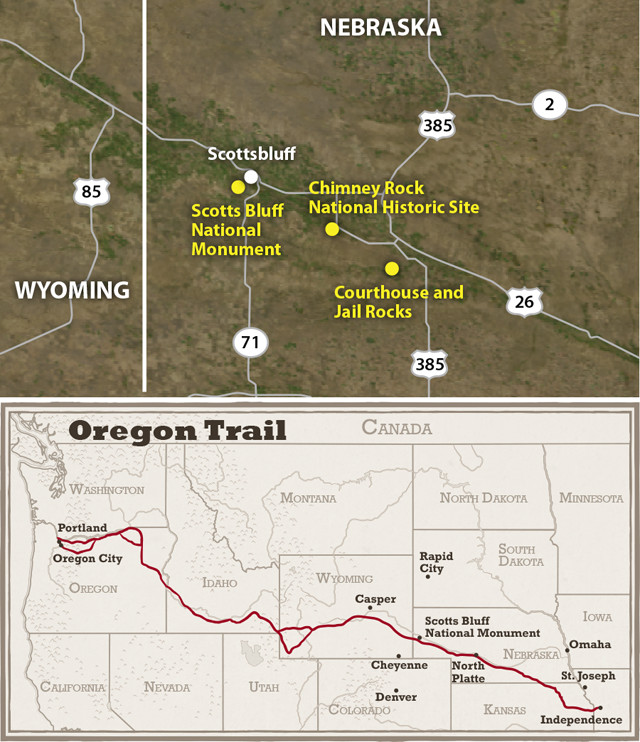

The Oregon Trail started in Independence, Mo., and wound its way 3,200 kilometers across parts of Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho and Oregon, where it ended in the verdant Willamette Valley. Courthouse Rock, then Chimney Rock, and finally, Scotts Bluff signaled to the emigrants that one-third of the trek to Oregon lay behind them. Today, these geoheritage sites are all within a day's drive. Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI

Roughly 70 million years ago, the Laramide orogeny — a major episode of mountain building to the west — began to uplift the Rocky Mountains. By 33 million years ago, the faults that raised the mountains had gone quiet, but massive volcanoes had sprung up across the West from Nevada to Colorado, belching ash that westerly winds hustled to Nebraska. For the next 27 million years, a steady rain of volcanic ash mixed with silt, sand and gravel eroded from the Rocky Mountains accumulated on the Great Plains. This 300-meter-thick pile of sediment became the White River and Arikaree groups and the younger Ogallala Formation. The gently east-sloping surface of this sediment pile became the surface of the High Plains.

The uppermost layers of the White River Group are composed of 33-million-year-old sediments from the Brule Formation. Following a gap in the rock record, late in the Oligocene, a mixture of windblown silt, known as loess, and mud that had eroded from the Rocky Mountains began to accumulate again, forming the 22-million-year-old Arikaree Group.

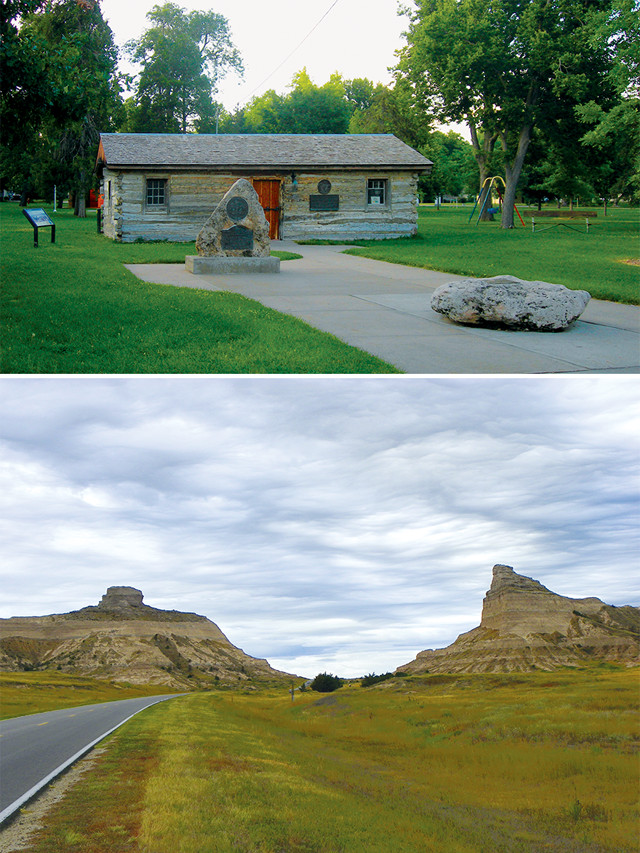

Top: An old Pony Express station in Gothenburg, Neb. Bottom: Nebraska State Highway 92 cuts through Scotts Bluff National Monument, a path the pioneers had to figure out on their own. One Native American name for Scotts Bluff is Me-a-pa-te, "hill-that-is-hard-to-go-around," and emigrants learned why the hard way: The topography here formed a barrier that blocked them from continuing to follow the banks of the North Platte River. Credit: Bottom: ©J. Stephen Conn; top: ©Jimmy S. Emerson, DVM

After deposition of the Ogallala Formation about 5 million years ago, Nebraska saw a switch from its long depositional history to an erosional regime. Geologists continue to debate whether this switch was caused by renewed uplift of the Rockies and the Great Plains or was, instead, the result of changes in global climate that invigorated the region’s rivers. This accelerated erosion began to cut deeply into the sedimentary stack, lowering the landscape and leaving the White River and Arikaree groups as the primary units exposed in the panhandle today. Where the rocks were unusually resistant, like at Scotts Bluff, they better withstood the erosional onslaught, leaving behind a series of towers. Farther west, in southeastern Wyoming, where the High Plains surface is nearly intact, the topography is more subdued. There it forms the Gangplank, the gradually inclined plain that Interstate 80 exploits to climb over the Rocky Mountains.

Scraps of History

Western Nebraska’s rock monuments are scraps of history, remnants of the once-continuous ancient High Plains that over time have been isolated by erosion.

The first monuments encountered by the fur traders, gold miners and pioneers along their 3,200-kilometer-long trek west were Courthouse and Jail Rocks, also called “Castle” or “Solitary Tower” in their journals. These imposing monuments served as a signpost of the crossroads between branches of the California and Oregon trails as well as the site of a Pony Express station during its brief existence. Courthouse and Jail Rocks’ lower cliffs are composed of 33-million-year-old sediments from the Brule Formation, whereas the rocks’ upper cliffs are composed of the Arikaree Group.

About 20 kilometers farther west, pioneers next encountered Chimney Rock, a slender, 36-meter-tall spire with similar makeup as the previous two. Chimney Rock was the most-noted landmark in diaries from the westward trails and is such a well-known symbol of the migrations that it is featured on the Nebraska state quarter. Today this monument is the centerpiece of a National Historic Site where visitors can pack their own wagon and examine original maps from Captain John Fremont’s 1842-1843 surveying expedition; his report guided thousands of emigrants along the Oregon Trail.

Credit: Bottom to top: ©Shutterstock.com/Zack Frank; ©Shutterstock.com/spiritofamerica; ©Jimmy S. Emerson, DVM

About 30 kilometers west of Chimney Rock, the westbound pioneers finally reached the imposing Scotts Bluff, a mesa-like erosional remnant, capped by the younger Arikaree Group but composed mainly of the Brule Formation’s Orella Member. This unit is loaded with well-preserved vertebrate fossils, including those of tortoise ancestors, oreodonts — a group of sheep-like mammals — and small ungulates known as “mouse deer.” Collectors and souvenir hunters frequently carted off fossils until 1910, when designation of the National Monument conferred protection to this geoheritage gem.

Scotts Bluff was named for Hiram Scott, a clerk from the Rocky Mountain Fur Company who, according to legend, was abandoned there in 1828 by his companions after he became ill. Prior to U.S. westward expansion, Native Americans had long roamed the area following vast buffalo herds, and Scotts Bluff was a major hunting ground of the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho. One Native American name for the bluff is Me-a-pa-te, “hill-that-is-hard-to-go-around,” and the emigrants soon learned why: The topography here formed a barrier that blocked them from continuing to follow the banks of the North Platte. To traverse the bluffs, two paths — which lie 13 kilometers apart — were forged through the so-called “Wildcat Hills” to the south.

Exploring the Region on Foot

Rock outcrops aren’t abundant in western Nebraska, but Scotts Bluff’s tall north flank is a stunning exception; there, geologists can examine a 230-meter-thick stack of sedimentary rocks, revealing the geologic history better than anywhere else in the state.

A good way to explore Scotts Bluff is to get out and hike the 2.6-kilometer-long Saddle Rock Trail, which begins east of the national monument visitor center and climbs to the top of the bluff. Located 800 meters up the trail in the Brule Formation is Scotts Spring — a trickle whose presence is now betrayed only by a pocket of lush vegetation — which once served as an important source of clean water for the pioneers and is purportedly where Hiram Scott’s skeleton was found.

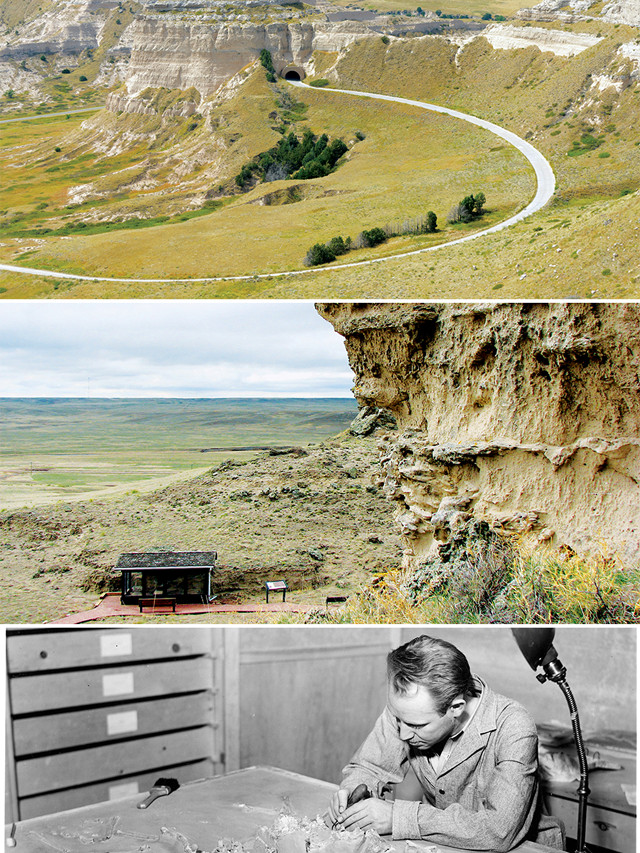

Credit: Bottom to top: National Archives and Records Administration; Terri Cook and Lon Abbott; ©Shutterstock.com/Zack Frank

Beyond the spring, the trail climbs gradually to a foot tunnel. Here, above the tunnel’s entrance, visitors can see a thin, gray layer of ash, transported here from a volcano to the west, as well as pronounced fossil footprints. Some of these were probably made by entelodonts, an extinct group of pig-like mammals with long muzzles and short legs that are sometimes nicknamed “hell pigs.” Other prints were likely made by oreodonts, rhinos, tapirs, small horses and camels.

The last third of the Saddle Rock Trail climbs from the foot tunnel to the summit through several active rockfall areas. Along this section, look for pipe-like concretions formed by groundwater-deposited lime. These hard rocks helped armor Scotts Bluff as the ancient plains surface eroded away around it.

Fossil Beds

A must-see in this region for any geo-traveler is one of the most important Miocene mammal sites in the world: Agate Fossil Beds National Monument.

Discovered in 1904, Agate Fossil Beds is remarkable for both the density of its bonebeds and its preservation of entire skeletons. Thousands of individuals died during what scientists think was an extended drought that occurred here about 19 million or 20 million years ago. As the vegetation disappeared, larger animals perished at the few remaining water holes, littering the area with their remains. The bones were then buried and eventually petrified by groundwater enriched in silica dissolved from volcanic ash.

The best way to see the site is to hike along the 4.3-kilometer-long Fossil Hills Trail, which begins at the visitor center. The most common mammal found in the bonebed is a three-toed, meter-high rhino, Menoceras. Other remains found here include Parahippus, the ancestor of the horse, and the fearsome-looking Daedon, which had bone-crushing teeth it used for scavenging.

Another quarry yielded numerous fossils of the small gazelle camel, Stenomylus, which scientists believe grazed in herds for protection. One mammal found less frequently is the carnivore Daphoenodon, a predator from the so-called “bear dog” family. Be sure to save enough time to walk the 1.6-kilometer-long Daemonelix Trail, where you can see the Devil’s Corkscrews — petrified burrows carved by Palaeocastor, land-burrowing beavers with clawed forelimbs that lived in colonies much like modern prairie dogs.

From Devil’s Corkscrews to Chimney Rock’s proud edifice, western Nebraska’s fascinating geoheritage sites — with their cultural significance and quintessentially Western and ever-evolving landscape — deserve a top spot on everyone’s list of travel destinations. At the very least, on your next cross-country drive, make it a point to stay a day or two in this region and explore these and some of the area’s other fascinating sites.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.