by Joshua Zaffos Monday, June 11, 2018

Arenal in Costa Rica is actively erupting. Night is a great time to see the volcano in action. Credit: right: ©iStockphoto.com/Rob Knight Inc; left: ©Scott Robinson, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic

Costa Rica is the happiest place on Earth, according to a 2009 survey by a London economic think tank. Credit the strong coffee and refreshing batidos — milkshakes with fresh banana, papaya, mango or some other tropical treat — and the country’s pura vida attitude that celebrates living life to the fullest.

Costa Rica’s calm and contentment are infectious, courtesy of the welcoming citizens, who call themselves Ticos, and the jaw-droppingly beautiful landscapes. There is no algorithm that determines how the beaches, rainforests and volcanoes add up to give Ticos the world’s highest “life satisfaction” and place them near the top of the global list for longest average life expectancy. However, a journey across Costa Rica provides ample proof that the remnants and reminders of its rowdy geophysical history are a major cause of bliss.

Credit: AGI/NASA

What makes Costa Rica a geo-traveler’s hot spot is actually located off the country’s western shore, where two tectonic plates meet deep beneath the surf. This active tectonic boundary has shaped the country’s landscape for millions of years.

Costa Rica sits on the edge of the Pacific Ring of Fire, the most active seismic area on the planet. The landmass perches over the boundary where the Cocos Plate and the Caribbean Plate crash into each other at the geologically rapid speed of 9 centimeters per year. The collision forms part of an active subduction zone, called the Middle America Trench, which extends from Mexico to Costa Rica along Central America’s Pacific coast and reaches depths of more than 6,000 meters.

One segment of this subduction zone, known as the Nicoya Seismic Gap, has proven to be a historically volatile quake area. The gap sits at a megathrust earthquake zone: As the Cocos Plate dives under the Caribbean Plate, the plates get stuck, allowing large amounts of stress to build up. Megathrust zones produce some of the planet’s most devastating earthquakes, such as the magnitude-9.0-plus quake that unleashed the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Costa Rica’s megathrust zone seems to work on a timer. Monstrous temblors have occurred with eerie regularity every 50 years; the last event, a magnitude-7.7 quake, happened in 1950, killing dozens of people. That means the Nicoya Seismic Gap is “mature” and due for its next release, according to seismologists at the National University of Costa Rica.

To see the active tectonics on full display, check out the Costa Rican highlands, where volcanic mountain ranges stretch like a spine through the interior part of the country. Just as the collision of the Cocos and Caribbean plates causes earthquakes, it also triggers volcanic activity. Such volcanism is responsible for creating the thin strip of land that connects North and South America. About 50 million years ago, the isthmus of Central America was part of the seafloor. Geologists think the configuration we know today started as an archipelago, a chain of islands that arose due to the active volcanoes.

Last January, Turrialba erupted for the first time in more than a century. Credit: ©Fbolanos, Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 3.0 Unported

Costa Rica is home to more than 60 dormant or extinct volcanoes and seven active ones. The most-visited volcanoes are in the northern half of the country, and many are located in national parks. Several of the sites are an easy car or bus ride from Costa Rica’s capital, San José, making them ideal day trips. Tour companies also offer guided group trips to volcanoes and parks, throwing in tours of coffee farms or zipline adventures along the way. Other parks are better suited to overnight visits, and travelers can stay at hotels in the surrounding small towns.

A good place to start a tour of Costa Rica’s volcanoes is a trip to the country’s liveliest. Arenal is located near the town of La Fortuna, about four hours north of San José. It’s a steep-sloped volcano with layers of hardened lava and ash, known as a stratovolcano. In 1968, after four centuries of quiescence, Arenal awoke with a bang: Lava and volcanic “bombs” of molten rock blew out of the volcano’s western flank. The episode killed 78 people, and marked the beginning of “strombolian” — frequent yet moderate — lava flows. These days, Arenal smokes and releases hot, glowing red avalanches of lava, which mesmerize visitors at night.

Costa Rica’s other active volcanoes don’t spew any lava today, but most researchers agree another major eruption isn’t a matter of if, but when. Nonetheless, the parks encompassing these sites allow travelers to get up close and personal with volcanic features.

Surrounded by coffee plantations, Poás Volcano National Park is Costa Rica’s busiest national park, partly due to its proximity to San José (only about 50 kilometers away) and the views it offers of the active crater that coughs up gas and ash, depending on the day. A short, wheelchair-accessible walk leads visitors to an overlook of the crater where they can stare down on Poás and its fumaroles and steam vents. Slightly longer hikes lead to panoramas of lakes that have filled in former craters. Only minor eruptions have occurred at Poás since 1954, but a January 2009 earthquake near the volcano was felt throughout all of Costa Rica and killed more than 30 people.

The crater of Poás. The volcano has not had a major eruption since 1954, but it continues to emit gas and steam. Credit: ©Peter Andersen, Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 3.0; inset: ©Edward Weston, Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 2.0 Generic

Turrialba, a two-hour drive east from San José, has rumbled even more recently. Spanish explorers noted that the volcano was smoking when they first arrived in Costa Rica in the 1500s, yet Turrialba has been tame since the 19th century — and until recently, some rustic trails even allowed hikers to walk along the edge of the volcano crater. But last January, Turrialba erupted, spitting ash and steam for the first time in more than a century. The activity has since abated, but scientists continue to closely monitor the volcano. Travelers should inquire with hotel managers, tour operators or locals to ensure that the park, its trails and its overlooks are open to visitors.

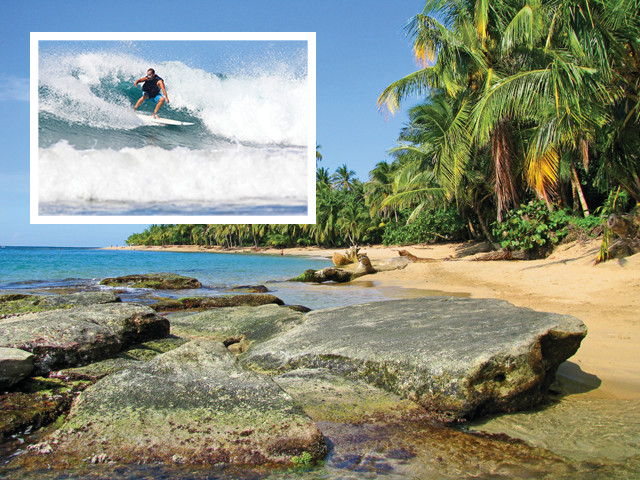

Costa Rica has other scenery to offer: If you’re a fan of surfing and sunning, some of the most popular beaches are found to the north along the Pacific Ocean in Guanacaste province and along the Nicoya Peninsula. Tourists can rent cars from San José (the drive takes five hours and may require navigating some very rough roads), ride buses or fly into the northern city of Liberia to get to the peninsula. As with much of Costa Rica, access and accommodations — from high-end hotels to simple bungalows — vary greatly from town to town.

The coast also varies its appearance. Beaches take on different colors, composition and size based on their orientation to the ocean and their proximity to rivers flowing from the inland mountains. The great surf spots — like Tamarindo and Santa Teresa, where big Pacific waves get the blood flowing — attract novices and experts alike, but just about every beach offers chances to get a tan and spot wildlife, from sea turtles to monkeys.

Costa Rica's beaches attract both sunbathers and surfers. Surfing is popular at the beaches along Guanacaste province and the Nicoya Peninsula in northwestern Costa Rica. Credit: ©baxterclaus, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic; inset: ©iStockphoto.com/Ian McDonnell

If you find Costa Rica’s rainforests more enticing than its beaches or volcanoes, head south: The Inter-American Highway leads away from San José before climbing along the Cerro de la Muerte, or Mountain of Death, an epithet referring to the foreboding elevation and weather the mountain once posed to foot travelers. As drivers climb more than 1,500 meters up the mountain along the highway, they must contend with mist, fog and adventurous Tico drivers who aren’t shy about passing.

Left A view of Cerro de la Muerte ("Mountain of Death") from the city of San Isidro de El General. Right: Colorful birds, such as scarlet macaws, soar through Costa Rica's skies. Credit: left: ©Michael Myers; ©Lsobrado, Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 3.0 Unported; right: ©Kelsey Pullar

Chirripó National Park is home to Costa Rica's tallest mountain. Visitors who hike up the mountain will see the high-elevation shrub and grassland habitat called páramo. Credit: both: ©Michael R. McLaughlin

Left: Visitors need to be careful where they swim in Costa Rica. Crocodiles lurk in many of the country's waterways. Right: Costa Rica is home to an abundance of wildlife, including this capuchin monkey. Credit: left: ©Adam Baker, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic; right: ©Joe P. Regan

The Cerro de la Muerte marks the northern reaches of the páramo, a high-elevation shrub and grassland habitat that ranges south into the northern Andes and attracts a diversity of wildlife. The fluctuating elevation accounts for a wide range of vegetation and climate, which has made Costa Rica a bridge for flora and fauna dispersing between North and South America for several million years. Most travelers take in the landscape from vehicle windows, but lodges and private tour operators in the region can arrange bird-watching, wildlife-viewing and adventure excursions.

The small city of San Isidro de El General is the largest population center in the south, and the town provides access to Chirripó National Park, where backpackers can undertake the strenuous climb up Costa Rica’s highest mountain, 3,819-meter Chirripó. The hike isn’t technical, but it does require a permit and an overnight stay at a high-country hut inside the park. Guide services in San Isidro can lead and coordinate backpacking trips and offer advice to those looking to explore the mountain on their own.

inset: ©iStockphoto.com/Focus-on-nature; bottom: ©Mike Baird, Creative Commons Attribution Generic 2.0

If you travel all the way to the southern Pacific coast, you can skip the Inter-American and opt for the coastal highway, which is now almost entirely paved. The road goes past the resort town of Jacó, the popular national park Manuel Antonio, and seemingly endless ceviche stands and rows of palm plantations. Although it’s Costa Rica’s smallest national park, Manuel Antonio encompasses shorelines and rainforests, where visitors are likely to see several species of monkeys and other creatures.

If you have a lot of time and a hankering for the wild, make your way to the Osa Peninsula at the southern tip of Costa Rica. The peninsula is covered by dense forest vegetation, and the environment is bustling with wildlife, including tropical and shore birds. In general, the peninsula is less developed than other parts of the country, although it isn’t unknown to tourists. The scattered towns offer a range of services, including campgrounds, eco-resorts and standard hotels.

Visitors to Corcovado National Park can stay at the park's research station, Sirena — but getting there requires either a boat ride or an arduous hike through the park's interior. Credit: ©Suzi Pratt

The jewel of the peninsula is Corcovado National Park, which covers almost 42,500 hectares of protected rainforest that stretches to the coastline where vine-covered trees come right up to the beach. In the past, the peninsula attracted gold miners, and some locals say major deposits remain untouched — and are now off-limits — inside park boundaries. Amateur prospectors can try panning in rivers, and guides will rent supplies and offer advice.

Getting into Corcovado requires long drives on rough roads and either boat transport or a very arduous hike to explore the park’s interior and stay at its research station, Sirena. Tours can be arranged through local hotels or private guide services. The payoff is an opportunity to wander around one of the most biologically diverse places on the planet.

Four species of monkeys spring through the trees. Scarlet macaws and toucans soar the skies. Peccaries, three-toed sloths, anteaters and several species of wild cats, including jaguars, can all be spotted in Corcovado and around the peninsula. At Sirena, park visitors can see Baird’s tapirs (think of slow-moving, hornless rhinos), and watch crocodiles and sharks cruise around river mouths emptying into the ocean as the tides change.

Between the flowing lava, the impulsive drivers, the lurking crocodiles and jaguars, and the looming Big One, it sounds easy to get caught up in Costa Rica’s thrilling landscapes. But visitors are also charmed by the unparalleled beauty of the country and the sweet disposition of Tico culture.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.