by Callan Bentley Friday, March 23, 2018

The village of Saint-Cirq-Lapopie is built on a hill above the Lot River Valley. Credit: Callan Bentley.

The Causses du Quercy Natural Regional Park, usually just called “the Causses” (pronounced like “coast” without the “t”), in south-central France is a classic Gallic landscape of gently rolling hills divided millennia ago into farm plots, livestock grazing pastures, low, dense forests and small stone-carved towns. It’s a place where the roads curve and wiggle, the butterflies dance in the sun, and people take long lunches at outdoor patios adjacent to the local “auberge” (inn). Strolling along the tree-lined roads, you hear the buzz of insects and glimpse backyard vegetable gardens, and after a tiny car passes you with a wave, you discover a Neolithic tomb, or dolmen, surrounded by vines. The dolmen speaks profoundly of how humans have inhabited the Causses for a very long time.

In short, it’s utterly charming. The vibe of pastoral France is exuded by the Causses. It’s been designated a UNESCO World Heritage “agro-pastoral cultural landscape” since 2011. And in 2017, the Causses region was named a UNESCO Geopark.

The region wasn’t named a geopark because of its limestones, which are unremarkable, but because it’s been transformed into a karstic wonderland by the slow dissolution of those limestones by groundwater. The caves that resulted are fascinating in their own right, but also because they served as shelters for some of the oldest members of our species. The term “Cro-Magnon” has come to be applied to these oldest Homo sapiens sapiens, named for a site here in the Causses. The Cro-Magnons, their descendants, and their neighbors, the Neanderthals, all occupied caves in this region, and they left their bones, tools and art behind as a record for us to ponder.

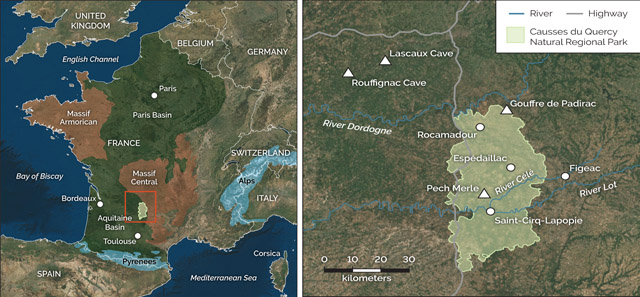

The easiest way to get to the Causses du Quercy is to fly to Toulouse and then drive north. Hundreds of caves underlie the region, and dozens are emblazoned with the art of ancient humans. Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI.

The geological map of France is divided into six main zones: two broad domes of metamorphic “basement” rocks that bulge up — the Armorican Massif and the Massif Central — and two broad downwarped regions, the Paris Basin and the Aquitaine Basin. This quartet is flanked by two mountain belts: the Pyrenees that run across the country’s southern border with Spain, and the Alps, poking into France’s eastern margin, on the border with Italy and Switzerland. Last summer, I traveled to a limestone plateau region in the smaller of the two basins, the Aquitaine, which is about half the size of the Paris Basin. The plateau’s limestone layers are Middle and Late Jurassic in age and dip ever so slightly to the west. I didn’t see any beautiful reef complexes or exquisite troves of fossils, but it was a delight all the same and very much worth visiting, as it hosts a stunning series of rural landscapes, caves and historical sites.

The limestone walls of the Célé River Valley host caves such as the famed Pech Merle, home to some 800 cave paintings. Credit: Callan Bentley.

Flying into Toulouse, the nearest large city, my family drove about an hour north into the “county” of Lot, about a third of which is designated as the Causses. The Causses lies south of the River Dordogne, and is incised by the River Lot and the River Célé, which divide the region’s limestone into four plateaus: the Causse du Martel, the Causse de Gramat, the Causse de Limogne and the Causse Corrézien.

Neolithic tombs, known as dolmens, can be found throughout the Causses, speaking to how long humans have inhabited the region. Credit: Callan Bentley.

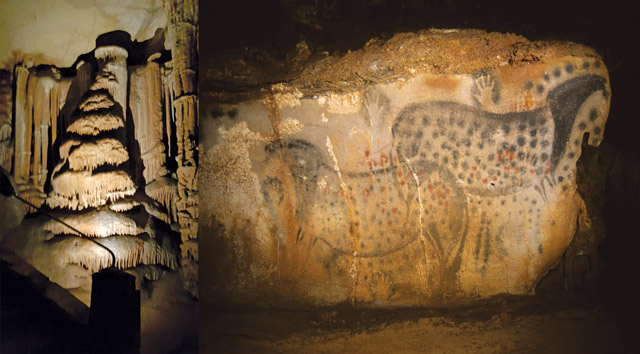

We stayed in the quiet village of Espédaillac, in the heart of the Causses. We began our exploration by driving through the stunning Célé River Valley to a cave called Pech Merle. The cave is a great place to observe large disc-shaped speleothems called shields, as well as cave pearls. There are, of course, many stalactites and stalagmites to admire as well, but the real reason to go to Pech Merle is to view some 800 cave paintings. Extraordinary images created using ochre and charcoal, they feature bison, aurochs (ancestral wild cattle), mammoths and a single big fish. An illustration of spotted horses is particularly renowned. And there are depictions that are less intuitively representative as well, such as a “wounded man” and patterns of handprints on the walls. Current thinking suggests that the oldest of these images were created 29,000 years ago by humans like us. In many places, visitors can see scratches in the soft limestone walls made by cave bears. These animal traces and the human art sometimes coexist on the same wall, a Paleolithic palimpsest.

Though the stalactites and stalagmites are plentiful in Pech Merle, the 29,000-year-old cave paintings are what draw visitors to the cave. Most famous is a spotted horse (shown here), though the site also has images of bison, aurochs (ancestral wild cattle), mammoths and a big fish, as well as handprints. Credit: left: Ben Sale, CC BY 2.0; above: Pech Merle Prehistory Center.

Jean-François Champollion, a philologist who deciphered the Rosetta Stone, was from the town of Figeac. A giant reproduction of the Rosetta Stone can be found in a small plaza between buildings, adjacent to Champollion's house. Credit: Callan Bentley.

A small museum above the cave entrance to Pech Merle displays human and Neanderthal remains, stone tools, cave bear skulls, and hyena coprolites. Credit: all: Callan Bentley.

A tidy museum above the cave entrance to Pech Merle displays human and Neanderthal remains, stone tools, cave bear skulls, and hyena coprolites. There’s also a short movie (in French, with English subtitles) about the cave’s discovery, significance and preservation. Access to the cave is allowed only with a guide on an official tour. Tours in English are offered several times a day; no photography is allowed.

After a visit to Pech Merle, I recommend kayaking the Célé River, as the waterline offers a lovely vantage point from which to see the Célé Valley. From the water, you can gaze up through leafy trees at the sheer limestone cliffs. Rapids are few and mild: This is a relaxing paddle, not a high-adrenaline experience. You can contract with a local outfitter for a boat and gear as well as a shuttle to the put-in spot, and the whole trip takes a couple of hours.

We drove back to Espédaillac via the Lot River Valley, mainly to visit the village of Saint-Cirq-Lapopie, which is built on a sloping cliff above the valley. Many people have described it as one of France’s most stunning villages because of this setting. It’s worth driving the steep and narrow roads to access this ancient town. There are numerous places to eat in Saint-Cirq-Lapopie, before or after navigating its labyrinthine streets and taking in the view of the Lot Valley from the top of a prominent natural limestone tower. Menus feature lamb, rabbit and plenty of hearty country fare.

“The town of Figeac along the Célé, where Jean-François Champollion lived in the early 19th century, is also worth a stop. Champollion was an accomplished philologist, known mainly for deciphering the Egyptian hieroglyphics on the Rosetta Stone found by Napoleon Bonaparte’s 1799 Egyptian expedition. A giant reproduction of the Rosetta Stone can be found in a small plaza between buildings, adjacent Champollion’s house. A nearby museum details Champollion’s life and work. The town of almost 10,000 is big enough to have a bustling market scene, and it can be quite lively on Saturday mornings.

Steep, narrow, winding roads lead to Saint-Cirq-Lapopie. Credit: Callan Bentley.

Next up is the Gouffre de Padirac, a truly awesome cave in the northern Causses. “Gouffre” translates as “chasm,” but Padirac is so much more than a mere chasm. You enter the cave complex through a massive sinkhole, so large it has an elevator to reach the bottom. (Alternatively, visitors can walk 10 flights of stairs.) From there, ramps and stairs lead deeper into the earth, where you walk underground for perhaps half a kilometer to a boat launch. A guide poles your boat along through a deep, dark declivity. Commentary is provided (but only in French). When you dock on the far side, you exit and meet with a new guide, who leads you on a half-kilometer walking circuit, up and down, past some amazing scenes — subterranean pools, ladders coated in a fur of calcite, and crazy speleothems that resemble stacks of plates or giant mushrooms. Then it’s back across the waterway on the boat, back to the sinkhole and up the elevator to the surface. Exit through the gift shop, of course.

Each year, more than 400,000 people visit the Gouffre de Padirac, where they can take in views of the vertiginous open-air entrance created when the cave's roof collapsed. Credit: Callan Bentley.

“Padirac lacks any human artifacts or remains. It is enticing purely on speleological grounds. I was impressed by the huge dimension, exhibited not just in the vertiginous open-air entrance but also in the cave’s enclosed underground areas too. Drops of water falling perhaps 100 meters from the cave roof explode on impact on the floor, generating those distinctive “stack of plates” speleothems. There’s also a lot of flowing water, clear as glass and moving right along as it continues its work making caves and speleothems.

A "stack of plates" speleothem forms in Padirac Cave as droplets from the cave ceiling, 100 meters above, splatter on impact. The cave hosts a series of shallow pools separated by rimstone dams. Credit: Callan Bentley.

Several ancillary attractions can be found nearby to the Gouffre de Padirac. Because we’re an entophilic family, we opted to spend an hour at Insectopia — within walking distance of the entrance to the chasm — where a small insect zoo aims to educate and impress its visitors with lovely, large specimens. We had the whole place to ourselves, and the adults enjoyed it as much as our 5-year-old son.

One of the "Stations of the Cross" along the path to the top at Rocamadour. The series of dioramas depicts the sentencing, execution and burial of Jesus. Credit: Callan Bentley.

From there, we headed to Rocamadour, one of the most popular tourist sites in southern France with a million visitors each year. Like Saint-Cirq-Lapopie, Rocamadour is a cliffside town that is improbably steep. However, it has an additional attraction: a religious site where Christians make a pilgrimage among 14 “Stations of the Cross” along a switchback path up the cliff. Each station is a diorama the size of a phone booth, with statues inside depicting the sentencing, execution and burial of Jesus. It’s been a pilgrimage site for many years, and is on one of the strands of the pilgrimage path to Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain. The shrine draws in many tourists, and as such, Rocamadour hosts all of the usual accompanying add-ons, including sweet shops and stores full of bric-a-brac. The ice cream is plentiful and welcome on a hot day.

An unexpected surprise occurs on the steps of the Grand Escalier, the 216 stairs that wind from the main street of Rocamadour up to the start of the zigzag route past the Stations of the Cross. In the steps are fossils of scallops and, more impressively, of belemnites, extinct cephalopods related to squid that lived only during the Mesozoic Era. These appear as dark cigar-shaped (and cigar-sized) features in the otherwise light gray rock. Despite being trampled by millions of feet every year, these stair-bound belemnite specimens look great and are among the best exposures I’ve seen.

The steps that lead from the main street of Rocamadour up to the start of the route past the Stations of the Cross host impressive belemnite fossils. Credit: both: Callan Bentley.

Rocamadour is one of the most popular tourist sites in southern France. Credit: Callan Bentley.

On another day, we visited yet more impressive caves about two hours northwest of Causses du Quercy Park. Grotte de Rouffignac is fascinating on several levels. The limestone there has oodles of chert nodules; in some places this silica makes up 40 percent of the rock volume. Chert like this was a useful source of sharp tools for early humans. The cave is partly filled with clay, and cave bears (now extinct) carved out fantastically large hibernation pits in the mud. These appear today as a nearly continuous array of deep holes the size of hot tubs in the cave floor. You can also see bear claw scratch marks on the walls, as at Pech Merle. Interestingly, no bear bones have been found there.

Grotte de Rouffignac (entrance shown here) hosts features like chert nodules and cave bear hibernation pits, as well as 14,000-year-old cave art. The drawings, all thought to have been completed in a week, were done as engravings and as manganese oxide drawings; some images combine both techniques. Credit: Callan Bentley.

“The cave art at Rouffignac was incredible. It’s estimated to be 14,000 years old, carved by Cro-Magnons, and all thought to have been done in the course of a week or so by between one and five artists. The drawings were done as engravings and as manganese oxide drawings; some images combine both techniques. Depicted are bison, horses, ibex, woolly rhinos and the ubiquitous mammoths, which are frequently depicted facing each other. One impressive mammoth frieze shows many individuals, but the lower half of the scene has been coated in calcite since the drawing. While this obscures the art, the coating authenticates the work as prehistoric. Additional features like fetlocks, manes, hair, hooves and eyebrows are all sketched out in detail, in a style called “Magdalenian,” which dates to the Upper Paleolithic between about 17,000 and 12,000 years ago.

“Touring Rouffignac offers a fun bonus for kids: a ride on an electric train that takes visitors quickly through the 1-kilometer length of publicly accessible cave — a small portion of the total 8 kilometers of passageways. Tours are only in French, and no photos are allowed. A major disappointment at Rouffignac was seeing the huge amount of graffiti on the walls, in some cases right on top of the ancient drawings.

Near Rouffignac is the famous Lascaux Cave. Lascaux has more than 6,000 figures drawn on its walls, most probably made between 17,190 and 15,500 years ago, which places them in the Magdalenian culture. The earliest carbon-14 dates here were done by none other than Willard Libby, who invented the technique. To protect this amazing trove of ancient art, the cave has been closed to the public since 1963. Fortunately, the public demand can be somewhat satiated by a popular full-scale replica of the cave and its art, dubbed Lascaux II. It’s encased in a glitzy modern building with lots of windows and light, and feels a bit like Disneyland, with prices to match. That said, as such facsimiles go, it’s a high-quality replica, and the artisans who produced it should be proud. Although Lascaux II does give you a sense of the actual cave, knowing it was fake nagged at my mind; I yearned to be able to visit the real thing.

Nearby, travelers can visit the L’Abri Cro-Magnon (the name means, essentially, “the hole on Mr. Magnon’s land”), the rock shelter where the first anatomically modern human remains were found. During the 1868 construction of a railroad, three human skeletons were unearthed at the site, along with partial remains of two other individuals. Anatomical study of the specimens showed that they were identical to modern humans, yet they lived 27,500 years ago. The term Cro-Magnon has since been applied to other finds of Homo sapiens sapiens, in other places and from other times, including as far back as 200,000 years ago. Though the original site suffered from decades of neglect, the rock shelter was recently restored, and a museum and nature walk were added that serve to attract travelers.

“Hundreds of other caves underlie the region in and around the Causses, and dozens are emblazoned with the art of ancient humans, but it’s hard to manage more than a few stops per day. As we commuted between the sites I’ve described here, we saw others, enticing and exotic, high up on the white cliffs around us. But we kept driving: There’s only so much time, and it’s good to know we’ll have plenty more to explore when we return.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.