by Saam Shams Friday, June 13, 2014

Credit: Ondrej Kozel

The author (center) and his Czech hiking companions (Vaclav Herda, left, and Vaclav Mulac, right) at the entrance to Tajik National Park. Credit: Ondrej Kozel.

There are moments in life when you need to catch some fresh air. For me, finishing my master’s degree and figuring out what to do next was such a moment. So, I set out to explore a land half a world away that I’d recently become familiar with, courtesy of a geotechnical engineering report about the world’s largest natural dam. Luckily, I speak Persian and am accustomed to backpacking in remote, high-altitude locations, so I was as prepared as I could be to travel to the backcountry of Tajikistan.

Tajikistan, a former Soviet republic, is nestled in the politically and geographically complex region of Central Asia along the ancient Silk Road; for centuries it served as a gateway between Western and Eastern Asia. The country has a long and proud history, but has never been well known to western civilizations and is not exactly a hotbed of tourism. Nonetheless, for adventurous geo-travelers, especially those with an interest in dynamic landscapes, Tajikistan offers amazing mountain and glacier climbing, endless backpacking possibilities, and the experience of feeling like you have traveled back in time. The country also has a reputation for its hospitality: In fact, strangers will often invite tourists back to their homes for a meal or lodging and ask nothing in return. Tajikistan is truly one of the world’s best-kept secrets.

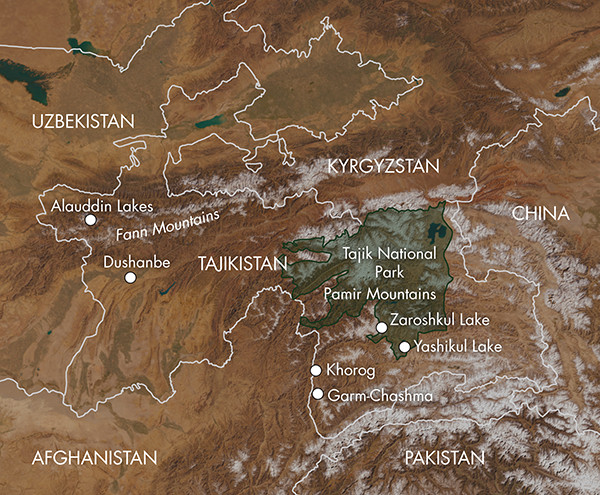

Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI.

I started planning my trip about four months before I set out for Tajikistan. I knew I wanted to backpack the Pamir Mountains and see as much of the country as I could during my three weeks there. I planned for about 10 days of backpacking and 10 days of sightseeing by car.

In mid-August 2013, I hopped a flight from LAX via Istanbul, Turkey, to Tajikistan’s capital, Dushanbe. Twenty-four hours later, I was in Dushanbe trying to hail a taxi to Khorog, the largest city in the Pamir Mountains. After another 16 hours and a harrowing shared van ride over dirt roads crossing incredibly unstable terrain, I arrived in Khorog at two in the morning. I woke up a hotel clerk — who was surprisingly pleasant given the time of night. Luckily, I had a room to spend the night.

The next day, I stopped by the Pamir Eco-Cultural Tourism Association (PECTA) office, a small wood cabin in the central park of Khorog right by the Panj River, to arrange my travel. Within an hour I had reserved a place to sleep in the Pamir Lodge homestay and a five-day backpacking trip with some tourists from the Czech Republic to explore the southern stretches of Tajik National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the Pamir Mountains.

One of many small lakes created by recent debris flows in Tajik National Park. Many of these lakes don't appear on Soviet-era maps of the region, as the lakes formed in the last 30 years. Credit: Saam Shams.

The Pamir Mountain Range is lodged between the Himalayan and Tien Shan ranges. It not only contains some of the highest peaks in the world but also boasts the longest nonpolar glacier, as well as the tallest natural dam on the planet. The Pamir Range is the creation of the continuing collision between the Indian and Eurasian plates — the same event that created Mount Everest. The region is underlain by very thick continental crust (about 70 kilometers) that is being pushed up as a result of this collision.

My travels took me mostly through the southwestern portion of the Pamirs, a region dominated by metamorphic rocks such as gneiss, quartzite and marble. The geology varies greatly across the Pamirs, as the northern regions are primarily composed of metamorphosed marine sandstones and limestones from the Carboniferous period (roughly 360 million to 300 million years ago). The region also appears to be rich in minerals, as evident from the many Soviet-era quarries. In fact, in many villages I encountered children trying to sell rubies and other precious gems. (In his writings, Marco Polo mentioned the abundance of precious rubies in the area.) Possessing and selling unlicensed precious stones is apparently illegal, but I didn’t see much enforcement.

The terrain throughout the Pamirs is incredibly unstable. The only way through the valleys is to hike over countless recent debris flows, composed of boulders and talus that often shift under the weight of one's foot — an unsettling feeling. Credit: Saam Shams.

We headed straight for Tajik National Park. The park covers 2.5 million hectares and is centered around the so-called Pamir Knot, a meeting point of the highest mountain ranges on the Eurasian continent, according to UNESCO. Our journey began with a taxi trip to the small village of Bachor, just west of a 20-kilometer-long lake called Yashikul. Along the way, our taxi driver invited us to his home for some food and tea. We accepted — it is expected in Tajikistan to accept such offers of hospitality from strangers — and found it was a great way to experience the life and hospitality of a typical Pamir villager. After arriving in Bachor, my new friends and I set out to explore the valleys of the Rushan Range as well as the high-alpine glaciers and lakes that cover the area.

The terrain throughout the Pamirs is incredibly unstable; it’s a very different setting than the granite domes of the Sierra Nevada to which I am accustomed. The rate of erosion is extraordinary. Rock slides and earthquakes are a common occurrence, and many villages have been destroyed in the past. The only way through the valleys is to hike over countless recent debris flows, composed of large, car-sized boulders that often shift under the weight of one’s foot — an unsettling feeling. The frequent sound of rock falls echoing in the background reminded us of the potential danger of another large rock slide. In fact, the whole area is so dynamic that the late Soviet-era maps we used to navigate did not even show one of the larger lakes we encountered on our path, indicating the lake had been impounded by a rock slide within the past 30 years or so.

Glaciers dominate the terrain of the high Pamirs. Credit: Ondrej Kozel.

We hiked 10 kilometers a day for five days, camping at night. The weather varied as much as the terrain. Once we reached 4,600 meters in elevation, we started encountering snow as we passed several large glaciers. We ended at Zaroshkul Lake, a breathtakingly large, high-elevation lake surrounded by snowy peaks.

We were largely isolated on the trip, encountering only a few other people. One night, we came upon a father and son who were herding cattle and had quite a distance yet to travel. (The son asked for my headlamp and, after first declining as I had only one, I soon realized he needed it more.) Although most of the land within the borders of Tajik National Park is protected from agricultural activity, the valleys of the southern areas of the park are accessible for locals to use for cattle grazing. It was common to see cattle at elevations up to 3,700 meters, where grass is still plentiful in the valley floors.

The author standing on the ruins of the Yamchun Fortress, built between the third and first centuries B.C., overlooking the Afghan Wakhan Range and the Hindu Kush. Credit: Saam Shams.

After days on my feet, I needed some time to recover before setting out on another backpacking adventure. At Pamir Lodge in Khorog, I met an array of interesting people, including a fascinating Swiss couple who had decided to ride bicycles from Thailand back home to Switzerland. They had just passed through Afghanistan and were making their way through Tajikistan to Uzbekistan.

Taxis, albeit mostly unofficial, are an easy and cheap way to get around Tajikistan, and it’s pretty easy to find people willing to share rides. Some French tourists and I hired a taxi to take us to a hot spring about 30 kilometers away in the city of Garm-Chasma. Another day, I joined a group of Israelis, a Frenchman and a Russian on a five-day expedition of the Ishkashim, Wakhan and Shakhdara regions in the southern Pamirs.

Although some segments of the roads in Tajikistan are paved, many are just gravel. Getting around is best done by taxi. Credit: Vaclav Mulac.

We explored numerous villages and ancient ruins from past Persian and other empires. In some spots, it was hard to distinguish which structures were old and which were new. Some of the fortresses, more than 2,000 years old, are completely surrounded by occupied homes built with exactly the same mud-and-rock construction style.

We had planned to visit a popular bazaar in Afghanistan right on the border, but Tajik officials closed the border due to a cholera outbreak. The Ishkashim and Wakhan regions of Tajikistan are a river-crossing away from Afghanistan. Instead, we made our way to the very small village of Bulunkul, situated on the east side of Yashikul Lake.

In this village, we stayed in the home of the principal of the local school. With only a handful of families living in the village, little to no infrastructure and seemingly no good areas for agriculture, I began to wonder why people would live here. Our hosts told us that, in reality, many villages in the Pamirs will only fully develop an economy beyond basic agriculture with outside assistance.

Crossing a bridge in the village of Bachor in the Pamirs. Credit: Ondrej Kozel.

After returning to Pamir Lodge, my new friends from the Czech Republic and I embarked on another backpacking trip, this one to the Fann Mountains in the north of the country. We spent three days hiking around the famous Alauddin Lakes. This region boasts some of the country’s largest pine forests and most picturesque scenery. Unlike the unstable Pamirs, the lower-elevation Fann Mountains are geologically more stable, and thus have allowed the growth of these old forests.

After nearly three weeks exploring Tajikistan, I felt like I had a good sense of the country, although there was still plenty left to explore. I was routinely humbled by the kindness of the locals. I trusted countless strangers with my belongings, traveled with strangers and stayed in the homes of strangers — all of whom quickly became friends.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.