by Terri Cook and Lon Abbott Wednesday, June 6, 2018

Few visitors to Colorado Springs, Colo., realize that the spectacular scenery on display at famous sites like Pikes Peak, Garden of the Gods, and the campus of the U.S. Air Force Academy is largely the result of varied geologic processes spanning more than a billion years. Pioneering 19th-century geologist Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden summed it up best when he said: “I do not know of any portion of the West where there is so much variety displayed in the geology as within a space of 10 miles square around Colorado [Springs].” In fact, the city holds the rare distinction of hosting rocks from every geologic time period save one. The presence of this unusually complete rock history means that while enjoying Colorado Springs’ premier attractions, you can also take a tour of the geologic timescale.

Atop a Precambrian Batholith

The best place to start your tour is on the 4,300-meter summit of Pikes Peak, which you can access by car, cog railway or a very challenging hike. The view from the jagged peaks to the vast plains below may inspire you like it did Katharine Lee Bates, who penned the stirring words of “America the Beautiful” from these lofty heights.

The entire mountain consists of pink granite that was intruded more than a billion years ago during the Precambrian eon. Known as the Pikes Peak Batholith, it is a prime example of “anorogenic” granite, meaning it was not emplaced during a typical mountain-building episode. Its unusual chemistry instead suggests it either formed at a hot spot, like modern-day Yellowstone National Park, or where Earth’s crust is actively stretching, like the East African Rift Zone.

A Day at the Paleozoic Beach

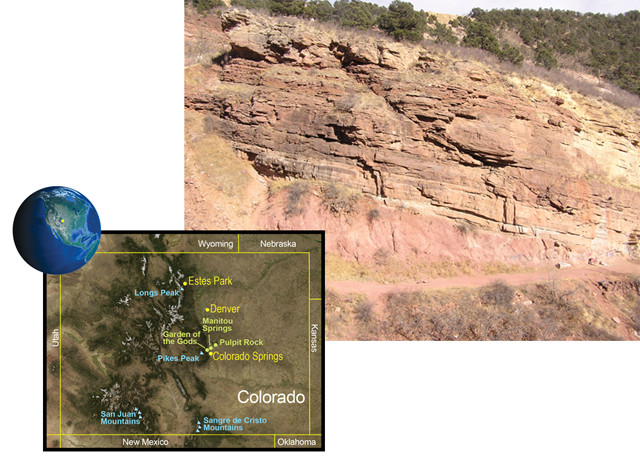

The next chapter of Colorado Springs’ storied past is told by the rocks exposed along the banks of Fountain Creek on the west side of Manitou Springs. Where Serpentine Road crosses the creek, an outcrop on the north side of a dirt road behind a historic sign consists of brown sandstone with layers tilted down to the east. This is the Sawatch Sandstone, deposited about 510 million years ago during the Cambrian, the oldest period of the Paleozoic era. About 50 meters up the road, more Pikes Peak granite peeks out below the sandstone. The boundary between these contrasting rocks marks an unconformity, a gap in the rock record that, here, spans about 500 million years.

Geologists can glean part of the story of the gap by considering the rocks on each side. Granite forms as magma solidifies far below Earth’s surface, in this case about 5 kilometers down. Yet sandstone is deposited on the Earth’s surface. Geologists therefore deduce that the 5 kilometers of material that once covered the granite had been completely eroded by the time the Sawatch Sandstone accumulated. It is tough to erode such a great thickness of rock unless it is elevated above sea level by tectonic processes, exposing the rock to enhanced weathering and erosion. This modest-looking unconformity therefore suggests that an entire mountain range rose in the Colorado Springs area during the late Precambrian. But during the Cambrian period, sea level was on the rise, and the ancestral Pacific Ocean flooded into Colorado from the west. The characteristics and fossils of the Sawatch Sandstone reveal that it accumulated in a beach setting, telling us that, by 510 million years ago, the mountain range had eroded back down to sea level.

The next rock in Colorado Springs’ layer-cake stack is the Manitou Limestone, deposited during the subsequent Ordovician period. You can examine it belowground during a spelunking tour through Cave of the Winds. Limestone is the predominant host for caves because it slowly dissolves in groundwater. But when the groundwater becomes supersaturated with ions of calcium and carbonate — the constituents of limestone — the dissolution process can reverse direction and remineralization can occur. Over millennia, the newly crystallized limestone grows into stalactites, stalagmites and other enchanting cave decorations.

The gap between the underlying pink Pikes Peak Batholith and the overlying Sawatch Sandstone spans half a billion years, during which a mountain range rose and eroded back to sea level in the Colorado Springs area. Credit: Maps: AGI/NASA; top: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook

The Manitou Limestone formed during an Ordovician sea-level rise similar to the earlier Cambrian one — except the Ordovician sea was deeper, so instead of being coastal real estate, Colorado Springs was completely submerged. Throughout the Ordovician and the three periods that followed — the Silurian, Devonian and Mississippian — Colorado was very close to sea level, allowing marine mudstone and limestone to accumulate during each episode of sea-level rise. Owing to a sea-level drop during the Devonian, the Silurian limestone was all but wiped out, and it is for this reason that the Silurian is the only geologic period for which Colorado Springs has no record. (Blocks of Silurian limestone were fortuitously preserved in the necks of small volcanoes in northern Colorado, so we do know of its existence.)

Later in the Devonian, sea levels rose again, leading to the deposition of the Williams Canyon Limestone. During the subsequent Mississippian period, yet another incursion of the sea deposited the 350-million-year-old Leadville Limestone. Impressive views of these layers are visible in the walls of Williams Canyon along the short, steep drive up to Cave of the Winds.

The lengthy stretch of tectonic peace and quiet Colorado enjoyed between the Cambrian and Mississippian periods ended 315 million years ago, during the Pennsylvanian period, when the supercontinent Pangaea assembled — with Gondwanaland colliding with North America in the vicinity of what is now Texas. Although Colorado was peripheral to the massive collision, the resulting stress raised a chain of mountainous islands, referred to as the Ancestral Rockies, across Colorado in roughly the same location as the modern Rockies. One of Colorado Springs’ thickest and most colorful rock units, the Fountain Formation, was deposited as alluvial fans that accumulated along the coasts of those rugged islands. You can examine the Fountain Formation’s brick-red layers of conglomerate, sandstone and mudstone at the Garden of the Gods and immediately south of the lower parking lot in the adjoining Red Rock Canyon Open Space.

Strolling into the Mesozoic

Red Rock Canyon offers delightful hiking through layers deposited during the next several geologic periods. Because the entire rock stack has been tilted steeply by faulting, it is possible to stroll from the Pennsylvanian through the Cretaceous — a span of 225 million years — in just a little more than a kilometer along the gentle Lower Hogback Trail, which departs from the upper parking lot of the Red Rock Canyon Open Space park.

The path first passes through a ridge of pink Lyons Sandstone. This is the remnant of a sea of Permian sand dunes that covered Colorado after the Ancestral Rockies had eroded to rolling hills and the climate in Pangaea’s interior became exceptionally dry. Exposures of the next two layers — the Permian-Triassic-aged Lykins Formation and the Jurassic Morrison Formation — are unfortunately both obscured beneath the fill of a former gravel pit, although both are beautifully exposed in the Highway 24 road cut about 0.2 kilometers north of the trail. Most of the Lykins Formation is brick red, like the Fountain Formation, but the rock is much finer grained. The Lykins also includes a limestone bed whose thin, wavy layers are stromatolites, the remains of bacterial mats that once grew on an arid tidal flat.

The Morrison Formation also consists of mudstone, fine sandstone and limestone, but it is easily distinguished by its gray, green and purple colors. The Morrison is one of the most famous rock formations in America thanks to its treasure trove of dinosaur bones. Dinosaurs, including Allosaurus, Stegosaurus and Apatosaurus, roamed the river floodplains and drank from the many lakes that dotted Colorado’s Jurassic landscape. Only a few bones have been recovered in Colorado Springs, but Garden Park, just 72 kilometers to the southwest, is one of the most productive fossil areas in the entire formation.

The rest of the Lower Hogback Trail crosses four additional layers deposited during the Cretaceous. It first climbs over the famous Dakota Sandstone, whose prominent ridge, or “hogback,” marks the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains. This sandstone accumulated on a beach about 100 million years ago when Colorado Springs was perched on the edge of a shallow interior seaway that covered the midcontinent. Tracks, logs and conifer cones found in this open space reveal that dinosaurs once wandered through here along a forested coastline. But as sea levels rose, the beach shifted westward, and crumbly gray Benton Shale, visible in the gentle valley between the Dakota and a smaller hogback to the east, accumulated in the seaway instead. As the water deepened, the shale also shifted westward, and the Niobrara Limestone, which forms the smaller hogback, was deposited. Where the trail ends at the 31st Street parking area, another gray shale, deposited on top of the Niobrara, is exposed. This is the Pierre Shale, which underlies much of the city of Colorado Springs and troubles engineering geologists with its expanding and contracting clay, which can crack foundations and heave roads.

Two additional Cretaceous layers are on display along Popes Bluffs in Ute Valley Park. The Fox Hills Sandstone consists of beach sand resembling the Dakota Sandstone, and together, the Dakota and the Fox Hills sandstones bookend the rise and fall of the interior seaway. As the sea finally drained away for good, the overlying Laramie Formation, with its abundant fossil leaves, was deposited on a humid coastal plain reminiscent of today’s Louisiana bayous.

Hiking Through the Cenozoic

During the Cretaceous-Paleogene transition, the Rocky Mountains were being built in the Colorado Springs region at the same time that two big faults — the Rampart Range and the Ute Pass — rumbled to life. One stretch of the Rampart Range Fault is visible in Garden of the Gods Park. The Tower of Babel consists of Lyons Sandstone that was shoved westward over the Fountain Formation along one strand of the fault.

As the new mountain range grew, powerful streams rushed down its flanks, depositing gravel in alluvial fans similar to those that formed the earlier Fountain Formation. Palmer, Austin Bluffs and Pulpit Rock city parks all offer scenic hiking through the Dawson Arkose, the sediment deposited on those fans. Its lowermost layers contain abundant volcanic rock fragments, revealing that, at their birth, the Rockies were crowned by volcanoes. The upper Dawson layers consist exclusively of quartz and feldspar derived from the erosion of granite. This sequence records the death and erosion of the volcanoes, which re-exposed the Pikes Peak Batholith.

The last 2 million years of the geologic timescale belong to the Quaternary, the period dominated by the Pleistocene ice ages. Glaciers crowned the Rockies during the Quaternary’s coldest snaps, then melted during warmer intervals. These fluctuations triggered alternating episodes of river deposition and erosion that have left a legacy of flat-topped mesas throughout the Colorado Springs area. The U.S. Air Force Academy’s famous chapel is built on one such mesa.

Mesa Overlook, perched on another Quaternary-aged mesa, is a great place to end your journey through the geologic timescale and soak up the amazing scenery created over the last billion years.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.