by Terri Cook Thursday, May 24, 2018

Provence, a region in southern France, is picturesquely nestled between the soaring Alps, the shining Mediterranean Sea, and the historic Rhône River. Credit: top: ©Shutterstock.com/Gordon Bell; bottom: Kathleen Cantner, AGI; globe: AGI/NASA

Nestled among the soaring Alps, the shining Mediterranean Sea, and the historic Rhône River, Provence, France — one of the world’s foremost tourist destinations — offers visitors scenic, gourmet, and geologic delights. The region’s rugged mountains, extensive plateaus and vineyard-lined slopes result from the Alpine orogeny, the mountain-building episode that uplifted the Pyrenees and the Alps in southwestern and southeastern France. The land in between was more modestly deformed, then gradually eroded over millions of years, to create the chefs-d’oeuvre — the masterpiece — that we now call Provence.

Like the dappled Provençal canvasses painted by Vincent van Gogh, the region itself is a swirling mosaic of sights, scents, sounds and tastes. Visitors can stroll through lively outdoor markets, sniff fragrant lavender fields, explore Roman ruins and quaint stone villages, and savor the world-renowned flavors and wines of the region. One taste of Provence will not be enough.

The story of Provence begins during the breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea about 200 million years ago, when a rift formed between the ancient landmasses of Laurasia to the north and Gondwana to the south. This rift gradually grew into the ancient Tethys Sea, the floor of which was blanketed with thick piles of predominantly shallow marine carbonates during the Mesozoic.

As Pangaea continued to split apart, Earth’s plates slowly reorganized. Africa moved north, creating a series of subduction zones along the Tethys Sea’s northern edge in which the oceanic crust under the Tethys was gradually subsumed.

The Provençal town of Orange is internationally renowned for its impressive Roman monuments, including the ancient theater, designed to seat 10,000 spectators (upper left), and an arch commemorating the Pax Romana, both built during the reign of Emperor Augustus Caesar. The Provençal town of Orange is internationally renowned for its impressive Roman monuments, including the ancient theater, designed to seat 10,000 spectators (upper left), and an arch commemorating the Pax Romana, both built during the reign of Emperor Augustus Caesar. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott

The resulting orogeny when Africa eventually crashed into Europe during the Cenozoic was not a single fender-bender, but rather a messy series of collisions that episodically raised mountain ranges across Europe. The Pyrenees were uplifted when the Iberian microplate slammed into the Eurasian Plate beginning in the Late Cretaceous. And the western Alps resulted from a similar but younger collision between the Eurasian Plate and another African fragment, the Adriatic Plate, hundreds of kilometers to the east.

Between these ranges, the southern edge of the Eurasian Plate was concurrently deformed, although to a much lesser extent. Instead of creating towering, Mont Blanc-like peaks, the sedimentary layers in this intervening area were more gently folded and faulted into Provence’s modest ranges, including the east-west trending Luberon Mountains, as well as a series of limestone highlands including the Vaucluse Plateau. West of these uplands, the Rhône River meets Provence just north of the town of Orange. And from there the river flows — through a valley carved into limestone and clay layers deposited after the uplift of the Alps — past steep, vineyard-covered hillsides, Roman ruins, and the cities of Avignon and Arles before lazing its way through the low-lying Camargue Delta en route to the sea.

Provence was settled by various groups, including the Ligurians, Greeks and Gauls, before the Romans conquered the area, establishing the province of Gallia Transalpina in the second century B.C. Because the area constituted the first sizeable Roman territory beyond the Italian peninsula, the Romans simply referred to the region as Provincia, the basis for its modern name. While in Provence, the Romans introduced Christianity, planted vineyards, and built scores of stone monuments so large and robust that thousands of years later they are still standing.

In northwestern Provence, the ancient theater of Orange is one of the best-preserved Roman theaters in the world and one of only three with a stage wall still standing, preserving the original acoustics. Designed to seat 10,000 spectators, the theater was built during Augustus Caesar’s reign (which lasted from 27 B.C. to 14 A.D.), and it is still used as a musical venue on summer nights. Orange also hosts an impressive arch also built by Augustus to commemorate the Pax Romana, established following Roman victories over the Gauls in 49 B.C.

On the Rhône’s opposite bank, located just outside Provence’s border, France’s best-known Roman monument, the three-story Pont du Gard, spans the Gardon River, a tributary of the Rhône. Built to support a section of the 50-kilometer-long Nîmes aqueduct, the 360-meter-long bridge is a technical and artistic masterpiece that is featured on the 5-euro bill. Assembled from 45,000 metric tons of soft limestone blocks excavated from a nearby riverside quarry, the bridge carried an estimated 200,000 cubic meters of water to the city of Nîmes each day.

Northeast of Orange, the town of Vaison-la-Romaine hosts the largest archaeological site in France: the remains of the Roman city Vasio Vocontiorum, built on the site of a Celtic tribal settlement following Rome’s conquest in 125–118 B.C. Today you can still see the theater, another beautiful stone bridge, noblemen’s homes, the foundations of the public baths, and even an old Roman sewer pipe, as well as a medieval 12th-century château.

In 1309, Pope Clement V, who was originally from Bordeaux, moved the papal seat of power from Rome to Avignon. He and the eight succeeding popes who reigned from there invested huge sums of money building and decorating the Papal Palace, the world’s largest Gothic palace and a UNESCO World Heritage Site well worth the visit. Although Provence became part of France in 1486, Avignon remained under papal control until the French Revolution.

Another famous attraction in this bustling university town is the remnants of the Pont Saint-Bénezet, the famous bridge of Avignon memorialized in a popular children’s rhyme. Completed over the Rhône in 1185, the bridge was washed out and rebuilt multiple times before its final demise in the mid-17th century. If the local mistral wind isn’t howling, Rocher des Doms Park offers a great vantage point from which to see the remains of the bridge and enjoy a picnic with panoramic views.

Rising 1,911 meters above the lowlands of central Provence, Mont Ventoux is the largest mountain in the area. Because it stands alone and has gained notoriety as one of the most grueling climbs in the Tour de France, it is frequently called the Giant of Provence.

Its summit of bare limestone gives the peak a snow-capped appearance year-round and hosts a harsh environment, with cold temperatures and recorded wind gusts up to 320 kilometers per hour. Thanks to its height and central location between the Alps and the Mediterranean, Mont Ventoux hosts a wide range of microclimates with an unusually diverse flora and fauna, including more than 1,000 species of plants, dozens of kinds of raptors and nesting birds, plus wild boars, deer and chamois. This biological uniqueness was internationally recognized in 1990 when UNESCO declared it a Biosphere Reserve.

Uplifted along the Nîmes Fault, Mont Ventoux towers above the surrounding vineyard-studded countryside. Its white limestone summit marks the end of a very challenging — and rewarding — bike ride. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott

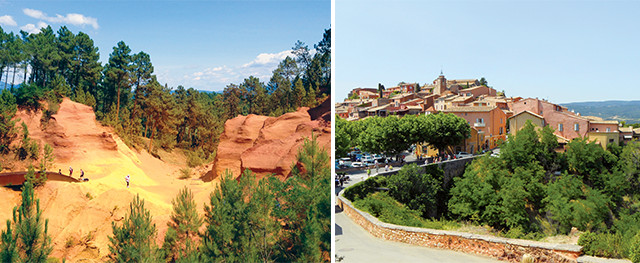

The village of Roussillon is very colorful, thanks to the local abundance of red, yellow and orange ochre, a powdery, natural oxide often used as a pigment, including by the Romans. Today visitors can stroll through one of the Roman quarries along the Ochre Trail. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott

Much of the uplift of Mont Ventoux has occurred along the Nîmes Fault, one of southeastern France’s major structures. The asymmetric mountain is steeper on its northern side, along the fault’s trace, but regardless of which side you approach it from, both the hiking and the biking are quite challenging. The classic bike route — featured about every two years in the Tour de France — ascends 22 kilometers up the southern slopes (with an average gradient of 7.1 percent) from the town of Bédoin to the summit. From spring through fall, hundreds of bikers ascend daily.

If you aren’t up for the ride, hiking in the Dentelles de Montmirail near the wine-growing center of Gigondas is another option. Here, the continuation of the Nîmes Fault is thought to disrupt Quaternary-age river terraces in the famous wine-growing area of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, indicating that it has been active within the last 2.5 million years. Paleoseismic evidence indicates earthquakes up to magnitude 6.5 have occurred on subsidiary faults in the last 10,000 to 50,000 years, including a magnitude-6 earthquake in 1909, raising the prospect of future seismic activity in the region. Convergence between Africa and Europe is still continuing in this area at a rate of about 0.8 centimeters a year.

Seventy-five kilometers south of Mont Ventoux, the Luberon mountain range is sliced in half by a narrow river valley, dividing it into the Petit and Grand Luberon. The Luberon is best known for its Lavender Route, among other scenic driving routes, which follows winding roads through breathtaking countryside and, in summer, vast fields carpeted with fragrant purple lavender blossoms. One of the best-known sites in southern France is the stone Abbaye Notre-Dame de Sénanque, which offers a picturesque background to the lavender plants plus a well-stocked gift shop where you can buy everything lavender, from bath items to cookies to cheese.

From the abbey you can walk or drive to the popular medieval village of Gordes, perched on the edge of the Vaucluse Plateau, another limestone highland raised by the Alpine orogeny. The area’s most interesting attraction is the nearby Bories Village, an open-air museum showcasing the remains of an ancient village of beehive-shaped, Bronze Age huts built out of local limestone slabs. It is not known exactly when these particular bories were built, but over the years, they have been modified and used for many purposes, including as wine cellars, homes and workshops.

Left: Gordes is a popular medieval village perched on the edge of the Vaucluse Plateau. Right: The Bories Village is an open-air museum showcasing the remains of an ancient village of beehive-shaped huts built out of local limestone slabs. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott

The Luberon is home to the international Luberon Geopark, which includes the Saignon Tracksite, one of Europe’s best-studied Paleogene fossil localities. During the Oligocene, the Saignon site was a pond or lake in a seasonal savanna-like setting. The largest tracks were made by the Oligocene rhinoceros Ronzotherium, and tracks by artiodactyls (a mammal similar to a deer in size), hyenas, goats and shorebirds are also common. The geopark also protects many Oligocene fossils — of fish, frogs, leaves and insects — so well preserved that exquisite details remain intact, right down to the individual lenses in an insect’s eye.

Also in the geopark, the colorful village of Roussillon shows off the local abundance of red, yellow and orange ochre, a powdery, natural oxide often used as a pigment. When the Romans controlled this area, they used the ochre for pottery glazes. Today, visitors can stroll through one of the former quarries along the Ochre Trail, a short path that winds among vibrant cliffs and sand-castle-like sculptures carved out of colorful sandstones deposited about 100 million years ago.

Continuing south, visitors encounter the flat wetlands around the Rhône River Delta, which differ starkly from the rest of Provence’s terrain. Known as the Camargue, this area south of Arles hosts one of the only sandy beaches in the region.

The vast wetlands are protected by the extensive Parc Naturel Régional de Camargue and are home to more than 500 species of birds, including flashy pink flamingos. The best place to see the flamingos, plus dozens of other species, is the Ornithological Park of the Bridge of Gau. You can also explore the wetlands on the back of a white Camargue horse.

After a fun-filled day near the coast, visit the town of Arles near sunset to get a sense of what Vincent van Gogh experienced and painted in the late 1880s. None of van Gogh’s 200-some paintings of this area are currently displayed in Arles, but the city has developed the Van Gogh Trail, an insightful walking route that visits locations where the artist once set up his easel. Sidewalk plaques, English-language brochures, and interpretive signs with reproductions of the paintings help you to see Arles from van Gogh’s perspective. After your walk, be sure to stop for dinner at the ancient Roman Place du Forum, home of Café la Nuit, thought to be the locale where van Gogh painted Le Café, Le Soir.

For centuries Provence has drawn invaders, pilgrims and artists from afar. Its idyllic location between the Pyrenees and the Alps has created a beautiful and hospitable landscape that, along with its agreeable climate and wealth of attractions, draws visitors over and over again.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.