by Randall Miller Thursday, January 5, 2012

The Bay of Fundy's high tides have eroded these Triassic rocks into 'flower pots.' New Brunswick Museum

The high tides of the Bay of Fundy have carved sea caves into the Triassic cliffs in St. Martins. New Brunswick Museum

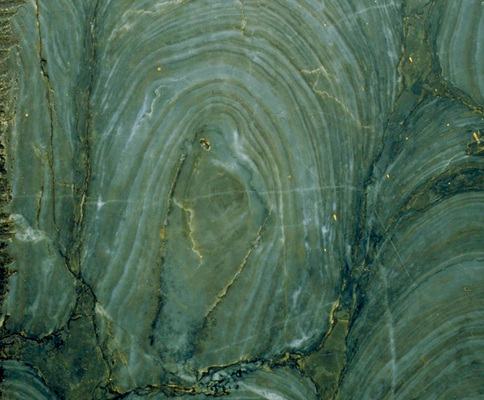

The Precambrian stromatolite _Archaeozoon acadiense_. New Brunswick Museum

Stonehammer Geopark lies along the rugged Bay of Fundy on Canada’s southeast coast. Centered on Canada’s oldest incorporated city, Saint John, New Brunswick, it is the first North American member of the Global Geoparks Network, 77 parks established over the past decade with the assistance of UNESCO. Geoparks strive to connect people with the landscape, highlighting the intersection of society and geology. They also encourage sustainable economic development, usually through geotourism. The result is a fun travel destination where geology is experienced in many ways.

Stonehammer was chosen as a geopark because of its extensive geological history and the region’s long tradition of inspiring geoscience research. Some of the first geological investigations in Canada occurred here. In fact, the park’s name honors this legacy. In 1857, a group of pioneering geologists formed the Steinhammer Club — steinhammer is German for stone hammer — to explore Saint John’s natural history. The complex geology of the city meant long-distance travel was not necessary for exploration. Within a short walk of their homes, these explorers could see Precambrian, Cambrian, Ordovician, Devonian, Mississippian, Pennsylvanian and Triassic outcrops overlain by late glacial marine and glacial sediments.

Just outside the city, sites with Silurian, Permian and Jurassic geology could be added to the list. Together these outcrops record more than 1 billion years of geologic activity — the opening and closing of oceans, the collision of landmasses, the emergence of complex life on Earth, and the advance and retreat of ice sheets. Today, visitors to the 2,500-square-kilometer Stonehammer Geopark can discover what drew — and continues to draw — so many amateur and professional geologists to the area.

The park’s key tourist attraction is also one of its youngest, geologically speaking. The Reversing Rapids (once known as the Reversing Falls) is named for the phenomenon that causes the Saint John River to reverse its course when the rising tides of the Bay of Fundy — the highest tides in the world, reaching 8 meters in Saint John — flood the estuary, pushing the river backward over a ridge of Precambrian marble.

The origin of these rapids dates to the last glacial maximum 20,000 years ago, when glaciers covered the area. Before the last glaciation, the Saint John River flowed to the sea through what is now Irving Nature Park, about five kilometers southwest of the rapids. As the glaciers retreated, moraines dammed the outlet of the pre-glacial river, causing the river to change course. By 15,000 years ago, the river found a new exit to the sea, flowing over the rock ridges at Reversing Rapids and carving out a gorge. The phenomenon of the Reversing Rapids began 3,000 years ago when the tides grew larger due to post-glacial sea-level rise and subsidence, allowing the river to overtop the Precambrian ridge.

The Reversing Rapids’ most famous geotourist was Charles Lyell. He visited the site in September 1852, after he discovered some of the world’s earliest reptile fossils in tree trunks at Joggins, Nova Scotia. In a letter to his father-in-law, Lyell described the rush of the tidal current in and out of the narrow gorge, formed from metamorphic rocks and vertical beds of shale. Today you can stand in Lyell’s footsteps and see the same view at the lookout on the 4.5-kilometer Harbour Passage Trail. Alternatively, you can sail on a tour boat through the gorge. Those who are more adventurous can ride on the Reversing Falls Jet Boat and pound over the impressive standing waves created by the tidal rush. For an even closer view, a zip line offers the chance to dangle over the rocks at Fallsview Park located on the north side of the Reversing Rapids Bridge that spans the Saint John River.

The Reversing Rapids is the most famous phenomenon left by the Pleistocene glaciers, but visitors to Stonehammer can also see other ways in which the ice sheets left their mark. In Irving Nature Park, the remains of a tidewater glacier complex can be seen where the glacier met the sea. You can also walk on the remains of a moraine — now the beach that connects the mainland to Taylors Island. Along the way, you can see fossils of clams, sea urchins and brittlestars eroding out of the coastal red clay cliffs that rise 9 to 15 meters. These cliffs were once the sea bottom when relative sea level was higher 14,000 to 12,000 years ago.

A much older story of the rapids is also gaining attention. The gorge that constricts the outlet of the Saint John River tells a tale of colliding ancient continents. Here two continental fragments, or terranes, came together as the Iapetus Ocean closed during the final assembly of Pangaea more than 300 million years ago. The Cambrian shales and sandstones south of the Reversing Rapids Bridge are remnants of the 542-million- to 490-million-year-old Avalonia (also known as the Caledonia Terrane). North of the bridge is the 1.2-billion- to 750-million-year-old Ashburn Formation marble — Precambrian light gray rocks of Ganderia (the Brookville Terrane). At Reversing Rapids, the Caledonia Fault, a shear zone, marks where the two terranes collided.

In 1890, the Ashburn Formation gave up a fossil secret that had eluded paleontologists for half a century. The search for the missing record of Precambrian life, often known as “Darwin’s Dilemma,” ended Oct. 7, when George Matthew, a member of the Steinhammer Club, described a find from a fossil locality on the west side of Saint John. At a lecture before the Natural History Society of New Brunswick, he presented a stromatolite, or sedimentary structure formed by alternating layers of cyanobacteria and mud, that he found along the shore of the Saint John River.

Named Archaeozoon acadiense, it was the first Precambrian fossil, and the first Precambrian stromatolite, described in the scientific literature (although the term stromatolite wasn’t coined until 1908). Visitors can still see examples of these stromatolites today. The best way to view them is by boat; from Dominion Park, you can book a 4.5-kilometer-long kayak adventure that paddles past the stromatolites and on to the remains of a 19th century lime quarry and kilns at the Precambrian-aged Green Head Group. The geology may compete for your attention with views of bald eagles resting in the trees overhead.

Across town you can trace the Caledonia Fault to Rockwood Park, where Avalonia lies to the south and Ganderia to the north. The park was designed by Calvert Vaux, co-designer of New York’s Central Park, and is the second-largest municipal park in Canada. If you arrive at lunchtime, Lily’s Café at the Lily Lake Pavilion serves a Stonehammer lunch with trilobite chowder and a Continental Collide dessert that will please your stomach as you enjoy the view across the lake. After lunch, make a stop at Daytripping Adventures across the hall from the café, which bills itself as “Not just another walk in the park.” The company offers rock climbing trips on a Precambrian volcanic outcrop or mountain bike rentals for some of the best trail riding in eastern Canada.

Stonehammer Geopark also offers many opportunities to explore geology outside of Saint John. Almost 60 kilometers northeast of the city, the small village of Norton hosts the fossil remains of almost 700 standing trees, making it the oldest “forest” in Canada. The 355-million-year-old rocks containing the trees are steeply tilted, exposing the trees end-on; nevertheless, they have provided data about forest structure in the Mississippian. Extinct Palaeoniscid fish and trace fossils have also been discovered here. These outcrops are not accessible to visitors, but a short trail out of Norton leads to a covered bridge crossing Moosehorn Creek, where the first fossils were discovered in the early 1900s. Exploring covered bridges is a highlight of this region; there are 10 in Stonehammer, most built in the early 20th century.

Back along the Bay of Fundy, 50 kilometers east of Saint John, the picturesque village of St. Martins offers views quite the opposite of Reversing Rapids. Whereas the rapids mark the location of an ocean closure, the coast along St. Martins offers a glimpse at the opening of the Atlantic Ocean. The Bay of Fundy is essentially a long valley that formed as an aulacogen, the failed arm of the triple junction rift system that created the Atlantic Ocean 250 million years ago and split apart Avalonia. River deposits and wind-blown dunes during the Permian and Triassic created the region’s spectacular red coastline.

East of St. Martins, a 10-kilometer drive or hike down the spectacular Fundy Trail Parkway will take you to Big Salmon River. Hiking trails at places like Melvin Beach provide access to the top of a plateau overlooking the red coastal rocks. The perfect way to end a Stonehammer adventure is a trip to the beach at St. Martins, where you can sit in the sand, ponder the area’s epic geology and enjoy the world’s best seafood chowder.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.