by Callan Bentley Wednesday, June 6, 2018

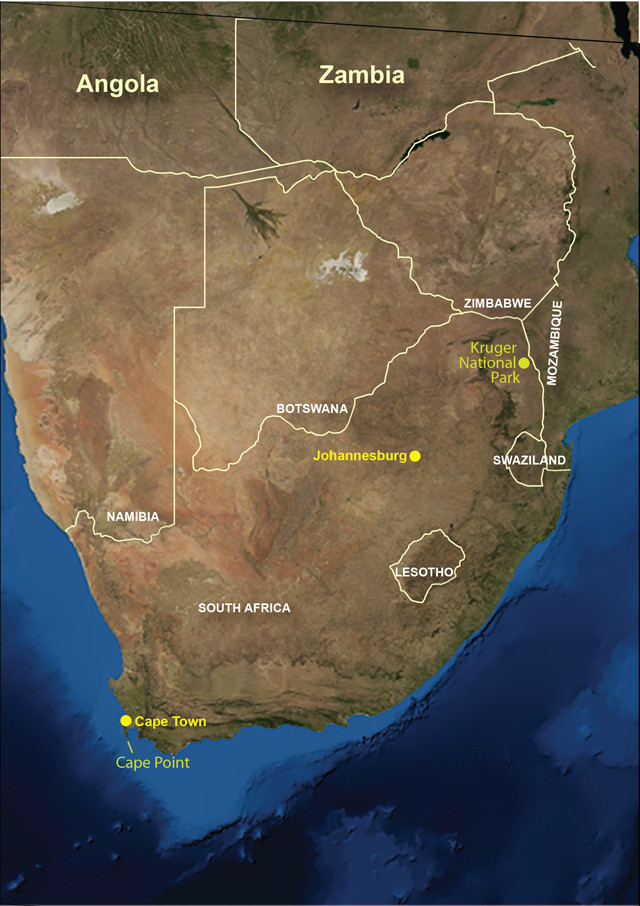

Credit: AGI/NASA

South Africa is hard to beat when it comes to diversity of nature. Whether we are talking about the country’s charismatic megafauna, its marine ecosystem, the unique fynbos plant community, or the extraordinary rock record, South Africa has something for everyone.

South Africa boasts the largest economy on the continent, thanks mainly to its geologic heritage, including the world’s largest gold and platinum deposits. The country has also produced most of the world’s gem-quality diamonds. Electricity to power the extraction of these mineral resources comes from vast tracts of coal — the compressed remains of Permian seed ferns called Glossopteris.

If the name Glossopteris rings a bell, it is probably because the species is a celebrated example of a fossil marking the connection of continents. Along with the freshwater reptile Mesosaurus, Alfred Wegener spotlighted the lowly seed fern a century ago when he proposed the breakup of Pangaea via continental drift.

Wegener used another line of evidence that linked South Africa to far-flung former neighbors: glacial deposits. These Permian glacial sediments are present in India, South America, Australia and Antarctica. Travelers to South Africa do not have to try too hard to find the distinctive, poorly sorted sedimentary rock diamictite of the Dwyka Group, a signature of the ice sheets that flowed here 250 million years ago.

The weather in South Africa today is, thankfully, distinctly nonglacial. My wife and I traveled there last winter with the goal of trading a cold, dark Mid-Atlantic winter for a summer solstice in the Southern Hemisphere and South Africa’s famous “Mediterranean” climate.

On Safari

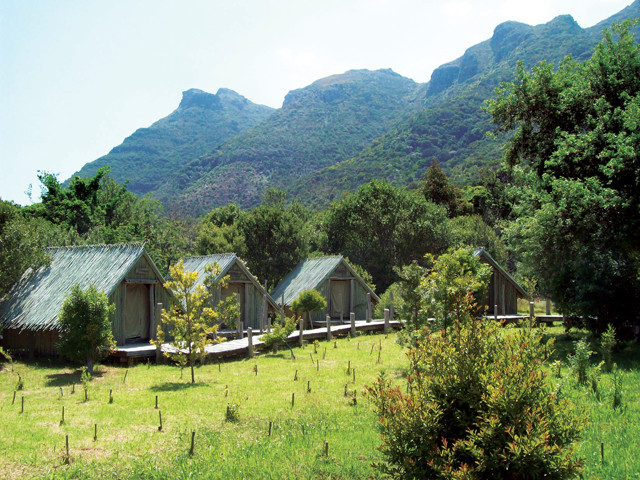

Orangekloof tented camp in Kruger National Park. Credit: Callan Bentley

Our first goal was to go on a safari, in search of the large beasts that still roam wild in the country’s legendary Kruger National Park. For five days, we explored Kruger with a guide in a Volkswagen Kombi. Tourists are encouraged to see the “big five” species: lion, leopard, elephant, rhinoceros and the African buffalo. We saw them all, but many of our most satisfying wildlife experiences were with smaller and less-famous species. I loved spotting the crested barbet, a beefy bird with a blend of crimson and golden feathers, and the fleshy geckos that hung out on the walls of our hut-like bungalows in the park. Best of all, we saw a genuine dung beetle, rolling his own little bolus of poop across the dirt road.

It is amazing to see these animals — familiar to Westerners through zoos and nature documentaries — in their actual habitat. The harsh, dry scrubland full of large animals also brings to mind the biodiversity of North America during the Pleistocene.

Animals seen on safari in South Africa. Credit: Alison Bentley

A visit to South Africa can also be a geological safari, in which the “big five” are the greenstone belts of the Kaapvaal Craton, the Vredefort impact structure and the Witwatersrand Supergroup near Johannesburg, and the Dwyka Group glacial sediments and the Cape Fold Belt, including Table Mountain, near Cape Town.

Kaapvaal Craton

Underlying Kruger Park is the Kaapvaal Craton, an Archean-aged protocontinent that mashed together with other protocontinents to form the African continent.

In Kimberley, South Africa, you can see the "big hole" left by the mining of diamond-bearing kimberlites. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Daleen Loest

The Dwyka diamictite is a Permian glacial deposit cited by Alfred Wegener as evidence of continental drift. Credit: Brian Romans

Within the Kaapvaal are several greenstone belts, celebrated examples of the suture zones between protocontinental nubbins. A fine example is the Barberton Greenstone Belt, south of Kruger and near the borders with Mozambique and Swaziland. This suite of metamorphosed volcanic and sedimentary rock is testament to the very different conditions on early Earth. For example, it is the type locality for komatiite, a rare ultramafic volcanic rock. Such a thing is effectively an oxymoron in the modern world, but back in the Archean, radioactive decay was much more intense than now. As a result, there was a lot more heat available to melt rock, including minerals with very high melting points. Olivine is the prime constituent of a komatiite, and appears in long needle-like crystals that piled up at the base of these ancient lava flows like a tangle of fiddlesticks. This “spinifex structure” is something that only happens if lava with a composition like Earth’s mantle erupts at a temperature of about 1,600 degrees Celsius. (Compare that to the relatively tepid 1,160 degrees Celsius of Kilauea’s lava in modern-day Hawaii.)

Exploring Johannesburg

In Johannesburg, you can visit the Vredefort dome, a massive extraterrestrial impact structure. With a diameter close to 300 kilometers, Vredefort is thought to have been produced about 2 billion years ago by a meteorite 5 to 10 kilometers across. The area is warped into a massive, multiringed crater. Even though the topography has been subdued by erosion, the concentric pattern is visible in Google Earth. See if you can find a chuck of suevite — glass produced in the tremendous heat of the impact and then rapidly chilled before it could recrystallize.

This spinifex structure of needle-like olivine crystals formed at the base of an ancient lava flow much hotter than modern lavas. Credit: Chris Rowan

Another geologic site can be found in downtown Johannesburg. As you fly into the city, you will see massive tailings piles, pale orange in color with distinctly anthropogenic geometry. This is processed gold ore, and it comes from the Witwatersrand Supergroup, a fascinating package of sedimentary rocks. Its upper portion, the Central Rand Group, bears five major layers of conglomerate that are highly auriferous, or gold bearing. These are Archean-aged placer deposits. Sometime between 3.1 billion and 2.7 billion years ago, primordial rivers sorted dense gold nuggets and sand into pockets of high concentration. The quartz-rich strata form ridges that poke up above the land. These are the source of the supergroup’s name: Witwatersrand means “ridge of white waters,” so named for the waterfalls that once poured off these ridges. (And in case you didn’t know, “W” is pronounced as a “V” in Afrikaans.) The association of these ridges with the gold deposits is memorialized in the contemporary use of the word “rand” for the currency of South Africa.

The ancient placer “reefs” of the Wits were first mined in 1887, and have since produced more than 50,000 tons of gold — about half the gold ever mined on Earth. Production has declined in recent years to about 400 tons per year, but it is still about 15 percent of the world’s annual total.

Directly across the street from the University of Witwatersrand is an extraordinary outcrop from the lower Witwatersrand Supergroup. “The Contorted Bed” is a folded banded iron formation unit that is beautiful to behold. Its red, black and white layers are folded into a variety of swirls and bends. It’s as visually captivating as the best abstract art, but also full of geologic meaning. The banded iron formation (BIF) is distinct on several levels: It is chemical rather than clastic sediment (though it has a much higher shale component than the BIFs I’ve seen in Wisconsin, Michigan and Minnesota); it is intensely folded in a way that the overlying and underlying quartzites are not; and it is basin-wide in extent. Because of its magnetism, the contorted bed is easy for geophysicists to trace in the subsurface. This makes it a superb marker-bed for figuring out one’s stratigraphic position within the Wits.

The Cape Peninsula

On your way south from Johannesburg to Cape Town, stop and check out the horizontal strata of the Karoo, which span the Permian-Triassic extinction event, or the glacial sediments of the Dwyka Group. Or perhaps swing into Kimberley, to see the “big hole” left when the diamond-bearing kimberlites there were all scooped away.

Architecturally, Cape Town is a rather ordinary looking city, but it is set in the most stunning landscape. The city proper is nestled into a bowl on the north side of Table Mountain; satellite suburbs are tucked into pockets between the mountains and the sea. Each is separated by cliffs and ridges, but connected by a ribbon of road. Unlike Johannesburg’s monotonous sprawl, Cape Town is charmingly balkanized. One hamlet you’ll want to visit is Sea Point, where there are coastal exposures of the Sea Point Migmatite, an injection of granitic magma into Late Proterozoic metasedimentary rocks. When the HMS Beagle docked in Cape Town in 1836, Charles Darwin stopped off at this outcrop and made one of his first geologic maps to document the contact between the granite and the host rock it intruded.

Nearby Table Mountain is an imposing presence that is frequently wreathed in a cloud layer known as the “tablecloth.” This UNESCO World Heritage Site is conserved as a national park. One good way to experience Table Mountain National Park in all its many guises is by hiking the Hoerikwaggo Trail. (The Khoisan tribe’s name for Table Mountain is pronounced Ho-Wreck-A-Va-Ko.) This new backpacking route has been blazed along the Cape Peninsula, connecting a series of comfortable tented camps with a path that traverses diverse landscapes.

Coastal exposure of the Sea Point Migmatite, an injection of granitic magma into Late Proterozoic metasedimentary rocks that was mapped by Charles Darwin in 1836. Credit: Callan Bentley

My wife and I hired a driver to take us 75 kilometers south to Cape Point, where we were dropped off at the lighthouse. Over the next five days, we walked north, back toward Cape Town. Most of the time, we were totally alone on the trail. During our first day of hiking, for instance, we saw only two other people over a distance of 20 kilometers. The route mainly traverses the Ordovician quartzites of the Table Mountain Group, which are mostly undeformed despite its location in the Cape Fold Belt, a Late Paleozoic mountain belt that formed as South America crunched in from the south to merge with Africa and form the supercontinent Gondwana. Though there are a few small folds along the Hoerikwaggo Trail that are interesting, most geotourists will have to make do with the lovely patterns produced by jointing and Liesegang banding of the quartzite. These rusty, chemically precipitated swirls enliven the scene, as do the white-naped ravens, the agama lizards, and the endless variety of odd plants in the fynbos — a scrubland biome native to South Africa.

Literally translated from Afrikaans, fynbos means “fine bush,” a reference to the fact that very few of these thin-stemmed species are suitable sources of lumber. What they lack in utility, however, they make up for in beauty and otherworldliness. Situated within the Cape Floral Kingdom — the world’s smallest floral kingdom (an area with relatively uniform botany) — the fynbos bears 9,000 plant species, about 70 percent of which are unique to South Africa. The giant woody flower called the protea, for instance, is a national symbol and the mascot for the country’s cricket team.

Our hike concluded one foggy day on top of Table Mountain overlooking Cape Town, which we descended to via the remarkable cable car system. In a seeming instant, we swooped down out of the clouds and into the sunshine. Moments later, we were back in the city at the base of the mountain.

All in all, South Africa offers visitors a wealth of zoological, botanical and geological experiences that cannot be duplicated anywhere else on the planet. It is a unique country with a distinct and diverse natural heritage, and it exerts a pull that no geologist can resist.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.