by Terri Cook Thursday, May 24, 2018

Credit: Mary Caperton Morton

Remember the scene in the beginning of “Mission Impossible 2” where Tom Cruise dangles from a cliff face high above a red rock canyon, hanging on by one hand? That’s Moab. Remember the cliff that Thelma and Louise drove off at the end of their on-screen adventure? That’s Moab. Remember the slot canyon in which James Franco got stuck in “127 Hours”? That’s Moab — or nearby anyway.

The high-desert canyons, cliffs and arches of the town of Moab, in southeastern Utah, are in fact featured in so many movies and commercials that even if you’ve never been there, you can rest assured that you’ve seen it. Nothing can compare to an actual visit though, especially if you’re a geologist, an adventure sports enthusiast, or both.

Rock climbing is one of the most popular activities around Moab. Credit: courtesy of Arbyreed

Nowhere is the quintessential Southwestern scenery — and the adventure sport industry built around it — more evident than in the small, bustling town of Moab, home to roughly 5,000 people and the world-famous Slickrock mountain biking trail. With a dry, sunny climate, frothing rivers, deep canyons, soaring rock towers, and monumental vistas of crimson-colored arches framing snow-capped peaks, Moab is an idyllic destination offering a lifetime’s worth of outdoor adventures. In a single day you can whitewater raft past colorful rock layers tilted by once-flowing salt deposits, bike across petrified sand dunes, hike among the world’s greatest concentration of stone arches, rock climb and BASE jump from sites made famous by the movies and stride in the footprints of dinosaurs. To top it off, you can quench your thirst following each activity with a luscious local wine or handcrafted beer.

Rafting Through an Old Ocean

The region was shaped by erosion by the Colorado River (as viewed here from Dead Horse Point). Credit: Mary Caperton Morto

Southeastern Utah is part of the broad Colorado Plateau, the high-desert region centered on the Four Corners (Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah), that is characterized by a thick layer cake of mostly flat-lying sedimentary rocks overlying a crystalline igneous and metamorphic base. On this plateau, the arid climate and erosion have created an otherworldly landscape of large, smooth sandstone slabs dotted with sparse vegetation colloquially known as “slickrock.”

About 300 million years ago, this part of Utah lay beneath the waves of the Paradox Sea, an inland body of water that — through changes in sea level and topography — was alternately connected to, and isolated from, the ocean 29 times over about 15 million years. When the sea was cut off, vast quantities of seawater evaporated in the near-equatorial climate, leaving behind salt deposits almost two kilometers thick. The area was then compressed during the uplift of an ancient mountain range to the east, causing the salt to flow like glacial ice. This movement thinned the salt layer in some areas, while in others the salt was thickened, pushing overlying rock layers up into northwest-to-southeast trending folds draped over salt cores up to three kilometers thick.

Throughout the Permian period and most of the subsequent Mesozoic era, from about 300 million to 70 million years ago, the salts were slowly buried by layer upon layer of sand and mud. More recently, as the Colorado Plateau was uplifted, the Colorado River and its tributaries began to carve into this layer cake, removing the uppermost layers and allowing rainwater to infiltrate the salt, ultimately dissolving and carrying much of it away. This process left behind cavities that subsequently collapsed, forming a series of several roughly parallel valleys that today slash diagonally across this portion of the plateau.

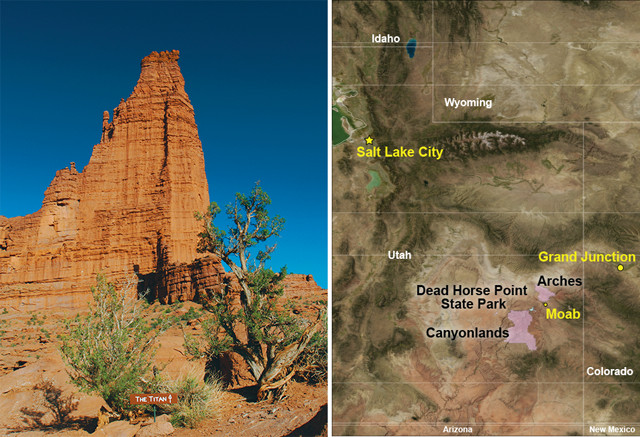

The crimson-colored Fisher Towers dominate the setting in Fisher Valley. This group of towers has appeared in more than two dozen movies and is a well-known destination for rock climbers and photographers.

Rafting is one of the area's highlights and a great way to immerse yourself in the landscape. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott

The region was also shaped by erosion from the mighty Colorado River, which slices through the valley ridges as it meanders to a major confluence with the Green River in Canyonlands National Park. Although most of the valleys in this area were carved by salt dissolution, Professor Valley — known for its whitewater rapids and ease of access via State Route 128, for those who wish to drive or bike it — was carved by the erosional power of the Colorado River. Rafting this beautiful stretch is one of the area’s highlights and a great way to immerse yourself in the landscape.

Many of the morning and full-day commercial rafting trips launch from the Hittle Bottom launch site. The first valley you raft through is Fisher Valley, in which you’ll see the crimson-colored Fisher Towers dominating the setting. This group of towers has appeared in more than two dozen movies and is a well-known destination for rock climbers and photographers. The towers are carved out of two of the colorful rock layers deposited atop the older Paradox salts — the Permian-aged Cutler and the overlying, Triassic-aged Moenkopi formations.

One spot that should not be missed is Delicate Arch, best viewed while hiking at about sunset. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton

From the river, more of the Southwestern sun-dappled scenery unfolds as you splash through Onion Creek, Professor Creek and Cloudburst rapids. From Ida Gulch Rapid, views to the southeast include Castleton Tower, which boasts a famous technical rock climb first ascended in 1961. Castleton is sculpted out of younger rock than the Fisher Towers; its steep sides are carved out of the Jurassic Wingate Sandstone, the preserved remnants of ancient, windblown sand dunes. You’ll also see another famous destination for hiking and photography, the Rectory, which is known for its anthropomorphized towers, The Priest and Nuns. Known as “castles,” these solitary towers are the resistant scraps of retreating cliffs of durable sandstone slowly chipped away via undercutting and landslides.

Many of the rafting trips stop at the Red Cliffs Ranch for a lunchtime barbecue before running Whites Rapid, the biggest whitewater on this stretch. In this vicinity at the mouth of Castle Valley, keep your eyes open for evidence of salt tectonics — crumpled layers of red sedimentary rock shoved aside as the salt flowed beneath. These deformed layers show that the salt continued to migrate well into the Mesozoic.

Slickrock, Slacklining, Soaking Up the Sun

The Moab area is known as a mountain biking mecca. The 18-kilometer Slickrock Trail is a world-famous mountain biking trek. Credit: : ©iStockphoto.com/Ben Blankenburg

If rafting isn’t your thing, try some of Moab’s other adventure sports, such as mountain biking. The Slickrock Trail, a challenging and world-famous 18-kilometer-long mountain biking loop, traverses the beautiful, buff-colored Navajo Sandstone, whose sweeping, high-angle cross-beds are the remnants of enormous dunes from a Saharan-sized desert that stretched from Arizona to Wyoming about 190 million years ago. With views down into Negro Bill Canyon — a wonderful hike accessible from State Route 128 — and the Colorado River, the Slickrock is a tough and unforgettable experience.

Road biking is also gaining popularity in the area (see sidebar), as are other thrilling activities, such as rock climbing and BASE jumping — a treacherous activity where participants jump off fixed objects using parachutes to break their falls; Moab is one of the only places in the world where people can tandem BASE jump. Slacklining, or highlining, is another activity gaining popularity in the area. It is similar to walking on a tightrope, except the rope is not stretched tight; rather, it has some give. Imagine doing that among the arches and canyons of the region!

And then, of course, there’s all the hiking to be done. Visitors to this region should spend at least a day — if not a week — exploring Arches National Park, located a short distance northeast of Moab. From the visitor center, it is a spectacular and steep drive — or bike ride — into the park past several additional Mesozoic-aged strata in the Colorado Plateau. The most important unit in the park is the Jurassic Entrada Sandstone, out of which are carved the park’s more than 2,000 arches and the famous Fiery Furnace fins, which are narrow ridges isolated by erosion of the weaker rock between them.

BASE jumping — jumping off a stationary object such as a cliff, with a parachute — is popular in the region. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Josh Schutz

You can explore the Fiery Furnace on a ranger-led hike or on your own, if you have advanced backcountry navigation skills. If you opt to hike it alone, you must obtain a special permit at the visitor center and should carry a map, compass and plenty of water. Hiking through the narrow, maze-like pathways of the Fiery Furnace, you’ll be treated to an up-close look at the spires and fins etched out of the Entrada, which, in this location, is the legacy of ancient sand dunes. One of the first things you’ll notice in the Fiery Furnace is that the fins are aligned with one another in the same, northwest-to-southeast orientation as the area’s salt anticlines. On the way to the Fiery Furnace is an expansive overlook of Salt Valley — a collapsed salt-cored fold — which has the same orientation.

When the salt valleys collapsed, the brittle overlying rocks cracked, creating fractures called joints, parallel to the valleys. Because joints allow water to percolate more easily into the subsurface, they increase the rate of weathering, ultimately enlarging them. Here, the joints are still closely spaced, whereas farther north at Devils Garden — a section of the park known for its remarkable concentration of arches — they are wider, most likely because they were exposed earlier and have experienced more erosion.

The other spot that should not be missed, even if you just have one day in Arches, is Delicate Arch, best viewed while hiking at about sunset. The first kilometer of the trail to Delicate Arch crosses the soft, pastel-colored muds of the Morrison Formation, a dinosaur-bone-rich unit deposited along vast floodplains in the Early Jurassic. Where the 4.8-kilometer-long trail begins to climb more steeply, the substrate switches to the Entrada’s distinctive pink slickrock surface, dotted with potholes, piñon pine and juniper trees. When you reach the sandstone amphitheater at the end, the sudden view of the La Sal Mountains framed by Delicate Arch is so spectacular that the state of Utah placed this scene on its license plates.

Slacklining, or highlining, is similar to walking a tightrope, except the rope isn't taut; it has a little give in it. It's a growing sport in Moab, where adventure sports enthusiasts like Jerry Miszewski walk across canyons. Credit: ©Jared Alden

Rock arches form out of fins like those in the Fiery Furnace. As the joints around a fin gradually expand, weathering processes can carve into the rock, creating an alcove that, under the right circumstances, can break through to the other side of the fin and leave a freestanding arch.

Delicate Arch sits at the contact between two sub-units in the Entrada, and the differences in composition and cementation between the two units provided enough contrast that dissolution and other weathering processes could slowly carve the rock into this masterpiece. Like all the park’s arches, Delicate Arch is ephemeral and will eventually collapse, as did Wall Arch, located along the Devils Garden Trail, during the night of Aug. 4, 2008.

Although hiking or biking is definitely the most hands-on way to experience Arches, the drive through the park is very scenic, and the visitor center and Park Avenue and Delicate Arch viewpoints are all handicapped-accessible.

Dinosaur Delights

No trip to Moab is complete without viewing at least one of the area’s dinosaur delights. The Copper Ridge Sauropod Tracksite preserves five trackways, including four made by three-toed theropods that sauntered on two legs. The fifth trackway, which looks like a series of large, bowl-shaped depressions heading northeast, was created by a 20-meter-tall sauropod — possibly a Diplodocus or Apatosaurus — that lumbered on all four legs.

The size and spacing of the larger theropod tracks are consistent with Allosaurus, the most commonly found carnivore fossils in the muddy Morrison Formation. Interestingly, the sauropod tracks show a pronounced turn to the right, an unusual feature in fossil trackways and one that is fun to ponder. Did it see a tasty snack and veer off course for dinner? Another interesting puzzle is the uneven spacing apparent in the easternmost theropod trackway. Paleontologists have suggested this irregular stride may have been due to a limp, or perhaps caused by the dinosaur carrying something heavy, like a chunk of fresh flesh gripped tightly in its gigantic jaws.

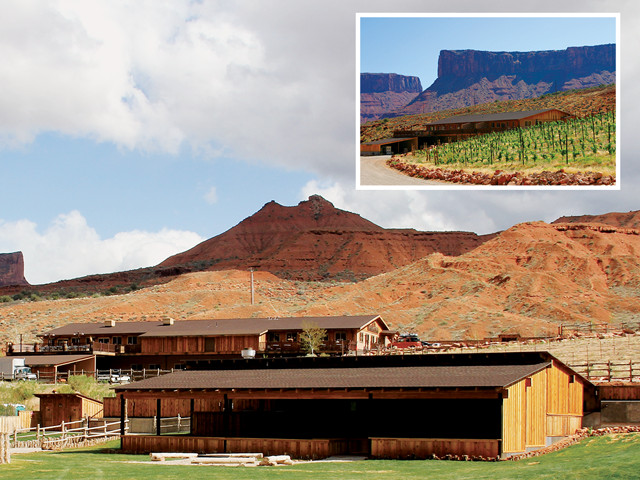

Utah's largest winery, Castle Creek Winery, is built on a historic working ranch. Also on the ranch is the Red Cliffs Lodge, which offers a restaurant, swanky accommodations and a large deck where you can drink in both the gorgeous views and the award-winning wine. Credit: Both: courtesy of Leo Boudreau

Along the Mill Canyon Dinosaur Trail, a self-guided stroll showcases more tracks as well as petrified wood and dinosaur bones still encased in the Morrison Formation. The short trail follows an ancient gravelly river channel, the resting site of a number of dinosaur bones thought to have been caught in the river current. Finds here include bones from a 9-meter-long Allosaurus, as well as several herbivores, including Stegosaurus, Camarasaurus and Camptosaurus.

This kid-friendly trail is located near the remnants of an old copper mill, perched on the south side of the canyon. The mill processed both malachite and azurite, copper ores that had been exposed along the nearby Moab Fault. The remains of an old railroad station are also located east of the trail.

Finding Time to Relax

If all the adventuring in and around Moab has you ready to relax, one of the best places to check out is Castle Creek Winery, built on the site of an historic working ranch just above Whites Rapid at milepost 14 on State Route 128. Utah’s largest winery offers self-guided tours and complimentary afternoon tastings of its internationally renowned wines. The vineyard capitalizes on the region’s dry, hot summer days and cooler nights to grow chardonnay and chenin blanc varietals, as well as pinot noir, merlot and cabernet sauvignon. Next door, the Red Cliffs Lodge offers a restaurant, swanky accommodations, and a large deck where you can drink in both the gorgeous views and the award-winning wine.

Ten kilometers south of Moab, the Spanish Valley Vineyards also has a tasting room where you can sample their wines, including cabernet sauvignon, chardonnay, gewürztraminer, and their sweet dessert wine, the Late Harvest Riesling.

Alternatively, like any good geologist, you can knock back a brew or two at the Moab Brewery, known for its fresh food, creamy gelato, and refreshing beer with creative names like Dead Horse Amber (named after the famed Dead Horse Point, the site featured in “Mission Impossible 2”) and Derailleur Ale (named for the part of a gearshift on a bike that derails the chain and moves it to another sprocket, in honor of the area’s prominence as a mountain-biking destination).

While you may have impressions of Moab after seeing a movie or two set there, when you’re there in person and kicking back with a beer or glass of wine after a long hike or bike ride, you’ll undoubtedly appreciate how much better it is to immerse yourself in the real thing.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.