by Terri Cook Friday, November 20, 2015

Credit: Tim Watson, CC BY-NC 2.0.

Built upon crimson slopes studded with junipers and towering pines, surrounded by soaring rock spires, and encircled by 800,000 hectares of pristine national forest, the central Arizona town of Sedona is widely recognized for its natural beauty. Sedona is also well known for its diverse recreational opportunities, flourishing art scene and its role as a hub of New Age healing.

Regardless of whether you come to visit Sedona’s large network of hiking, biking and off-road trails, its “energy vortices,” its up-and-coming wineries or its pampering spas, you are sure to draw inspiration from the area’s stunning red rocks, which owe their origin to a series of subtle geologic events that transpired more than a quarter of a billion years ago, when northern Arizona was perched at the very edge of a supercontinent.

Sedona, Ariz., is less than an hour's drive from Flagstaff and about two hours from Phoenix. Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI.

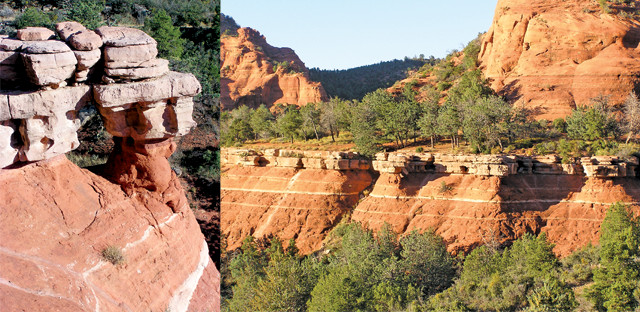

The Schnebly Hill Formation, which makes up the bulk of Sedona's stunning red rocks, lies between the Coconino Sandstone and the older Hermit Formation. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

The colorful sedimentary rocks of the Schnebly Formation were laid down as river sediments near the edge of Pangea. The Devil's Bridge, a natural sandstone arch north of Sedona, is a popular hiking destination. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

The story of Sedona’s iconic landscape begins near the end of the Paleozoic, a relatively tranquil time in northern Arizona’s geologic history. For hundreds of millions of years, a succession of shallow seas encroached upon the region and then waned, but tectonically, little else occurred. Meanwhile, in other, more tumultuous parts of the planet, a series of collisions had gradually amalgamated nearly all of Earth’s land into the supercontinent Pangea. The last stages of this assembly, which ended about 300 million years ago, uplifted a large mountain range stretching from the Appalachians to Colorado, called the Ancestral Appalachians. Northern Arizona lay west of these mountains, along Pangea’s western edge, perched on the shores of Panthalassa, the enormous global ocean that surrounded the supercontinent.

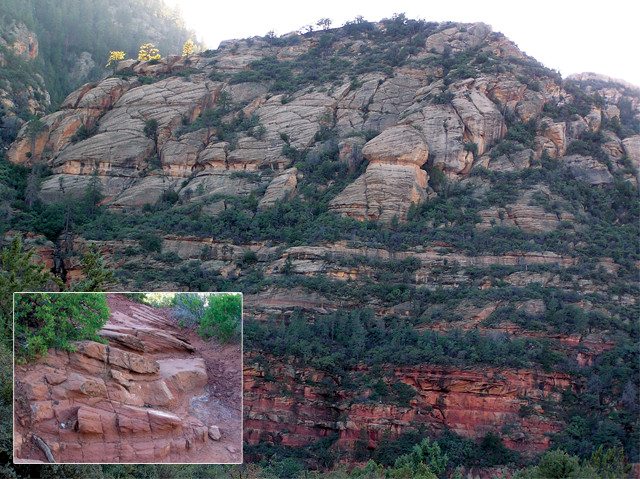

As soon as this range was uplifted, erosion began tearing down its peaks. Ancient rivers carried the resulting debris from these mountains — whose westernmost portion is known as the Ancestral Rockies — across northern Arizona, inundating the region with layers of silt and sand that would later be cemented into the Hermit Formation, Sedona’s brick-red bedrock.

Two hours’ drive north of Sedona, at the Grand Canyon, the Hermit Formation lies directly beneath the younger Coconino Sandstone, and the distinct contact between the two represents a 5-million-year gap in time, as well as a significant change in environment. In stark contrast to the Hermit’s predominant red mudstones, the blonde, coarse-grained Coconino hosts steeply angled, wind-blown crossbeds. These are the legacy of sand dunes up to 300 meters high that began blowing across the region about 275 million years ago in an enormous, Sahara-like desert after the climate became more arid.

But in Sedona, there is no large gap between the Hermit floodplains and the Coconino desert. Positioned at the edge of Pangea, Sedona experienced nearly continuous deposition along the supercontinent’s shoreline, which ultimately created an additional 200 meters of colorful sedimentary rocks between the two formations. It is these layers — collectively known as the Schnebly Hill Formation — that comprise the bulk of Sedona’s spectacular spires.

In the Grand Canyon, the lighter-colored Coconino lies directly above the Hermit, with a 5-million-year gap represented by the contact between them. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

At Bell Rock, named for its bell-like shape, visitors can see evidence of coastal tidal flats along Pangea's ancient shore. Credit: Jocelyn Kelly, CC BY-SA 2.0.

An outcrop of the Hermit Formation in Sedona. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Exploring this famous backdrop, which records the events that occurred along Pangea’s long-vanished coastline during the Late Permian, is the highlight of any trip to Sedona. There are myriad ways to do this, from Jeep trips up one of the scenic canyons carved into the adjacent plateau to strenuous canyon hikes or mellow strolls around one of the fancifully named scraps of red rock nestled in the neighboring valleys.

A great place to get started is Bell Rock, the distinctive, bell-shaped landmark (and site of one of Sedona’s purported energy vortices, where Earth’s power is said to emanate from the ground) located south of town. Here you can wander to the base of the rock, or climb an increasingly steep slope up its north side along the Bell Rock Trail. As you hike, keep an eye out for ripplemarks and parallel banding. These were created by tidal currents, which repeatedly washed sediments back and forth along coastal tidal flats 278 million years ago, when the Bell Rock sub-unit was deposited.

About a million years later, sea level rose slightly, submerging this part of the Pangean coastline. One of the best places to see the evidence of this, as well as many more of the famed red rocks, is along Schnebly Hill Road, a popular scenic drive that ascends the prominent canyon east of town. Because the rocky road is often impassible to passenger cars, it’s best to explore the slickrock paths, hidden picnic spots and expansive rock amphitheaters with a 4x4 rental or — if you prefer to focus on the rocks instead of the road — with one of Sedona’s entertaining Jeep tour companies.

Be sure to save enough time to walk at least a short distance up the Munds Wagon Trail, a 6.5-kilometer-long (one way) trail that begins at a small parking area on the left side of Schnebly Hill Road just after milepost 4. Just a five-minute stroll up this path are stunning views of red and white spires looming above red slopes dotted with evergreens. As you walk, look for a prominent, 3-meter-thick band of gray limestone. This is the Fort Apache sub-unit, deposited when the shallow sea flooded the area 277 million years ago. The fact that the layer is less than 3 meters thick indicates that this incursion did not last very long.

The 3-meter-thick band of gray limestone known as the Fort Apache sub-unit was deposited when a shallow sea flooded the area 277 million years ago. Credit: both: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

When the water receded slightly 1 million years later, the Fort Apache’s gray, knobby surface was covered with the rocks of the Sycamore Pass sub-unit. Although in places the Sycamore Pass rocks look quite similar to those at Bell Rock, intervals of crossbedded sand indicate that over the next million years, coastal dunes alternated with tidal flats in the Sedona area. The sections of crossbedded sand become thicker and more numerous higher up the canyon walls, especially in the zone of alternating red-and-white bands that mark the transition from the Schnebly Hill Formation to the overlying Coconino Sandstone, which caps most of Sedona’s red rocks.

The Chapel of the Holy Cross, a Roman Catholic chapel dramatically sited among some of the area's most spectacular red rocks, is considered an "energy vortex" by some. Credit: Brook Ward, CC BY-NC 2.0.

The Sedona area is home to several wineries, including Oak Creek Vineyards. Credit: Alan English, CC BY-NC 2.0.

Slide Rock State Park, a popular tourist location in Oak Creek Canyon, offers a red sandstone water chute that plummets into a crystal-clear swimming hole. Credit: Patrick, CC BY-SA 2.0.

No trip to Sedona would be complete without a drive up Oak Creek Canyon, a scenic, 20-kilometer-long gorge located in Coconino National Forest between Sedona and Flagstaff. As state Route 89A ascends the steep canyon via an impressive series of winding switchbacks, it climbs more than 1,300 meters in elevation. At the mouth of the canyon, 12 kilometers north of Sedona, Slide Rock State Park offers a red sandstone water chute that plummets into a crystal-clear swimming hole in a gorgeous slickrock setting.

There are also many excellent hikes that leave from the road, including the A.B. Young Trail, a strenuous, almost-4-kilometer-long (one way) hike that climbs up to the rim of Oak Creek Canyon before ending at the East Pocket fire lookout tower. Farther up the canyon, the first 5 kilometers of the West Fork Trail explore the beautiful riparian zone alongside the creek, which the path repeatedly crosses. Near the top of the drive, the Oak Creek Canyon vista point is a wonderful place to stop, drink in the views and ponder the much more recent geologic events that created this gorge.

From the overlook it’s easy to see that the canyon’s steep walls are topped by basalt, a dark volcanic rock that erupted as a series of lava flows from multiple fissures to the northeast. The youngest basalt capping the rims is estimated to be just 6 million years old — more than a quarter of a billion years younger than the Coconino and Schnebly Hill formations and other Paleozoic units that lie directly beneath it.

Because basalt of the same age is present on both canyon rims, the lava must have erupted before the modern Oak Creek Canyon was carved. The timing coincides with a period of continental extension, or stretching, that roiled the region. Geologists think this tension reactivated a pre-existing fault, causing the canyon’s eastern side to drop lower relative to its western side. This eastward-dipping motion has visibly offset the basalt and other rocks and left the eastern rim sitting about 200 meters lower than the west rim. Over the last 6 million years, the igneous cap rock sheltered the underlying Paleozoic sedimentary rocks, fortuitously helping to preserve the remnants of Pangea’s long-lost shoreline.

The Sycamore Pass sub-unit represents coastal dunes alternating with tidal flats. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

In addition to Bell Rock, Sedona’s other energy vortices include Airport Mesa, Boynton Canyon and the Chapel of the Holy Cross, a Roman Catholic chapel dramatically sited among some of the area’s most spectacular red rocks. Boynton Canyon is a great place to check out whether you can feel the vibes emanating from one of Sedona’s reputed vortices — and also enjoy amazing red-rock views. According to New Age beliefs, people can sense this vortex, which is centered upon the two rock formations rising above the end of the short Boynton Vista Trail, by resting their foreheads on the stone. It’s also a great picnic spot and is just a short distance off the moderate 10-kilometer (round trip) Boynton Canyon Trail, which is popular for its beautiful views and fall foliage.

When you are ready to relax, try checking out some of Sedona’s art galleries, which number in the dozens; or visit the area’s renowned spas or flourishing wineries, most of which can be found in the nearby Verde Valley. Three of the closest wineries are located just a few minutes’ drive southwest of Sedona along Page Springs Road. These include the Javelina Leap Vineyard and Winery, a family-operated winery specializing in zinfandel and other red wines grown on volcanic soils. The neighboring Page Springs Cellars offers Rhône-style blends made from grenache, syrah, mourvèdre and petite syrah grapes. Page Springs also offers massages. Finally, the adjacent Oak Creek Vineyards and Winery offers a larger selection of white wines as well as two dessert wines, the ruby-red Arizona Port and the smooth Arizona Cream Sherry, a blend of sweet, late-harvest chardonnay grapes with brandy.

Regardless of which you choose, kicking back with a glass of local wine and watching the sun set behind Sedona’s red rocks is a perfect way to end a day spent journeying on the edge of a supercontinent.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.