by Terri Cook and Lon Abbott Monday, July 2, 2018

Last spring, while many Americans were migrating south in search of sunshine, our family headed north to rainy Vancouver, British Columbia, so our high school-age son could visit two colleges and we could all explore the city’s vibrant downtown. In addition to touring the campuses, he wanted to find out whether British Columbia’s magnificent mountains and captivating coastline would hold opportunities for outdoor activities during the misty “mud season.” What we learned is that, in this corner of southwest Canada, there’s no offseason for outdoor pursuits. Thanks to the region’s tremendous topography, which rises from sea to sky over just a few kilometers, what’s rain in the city falls as abundant snow high in the mountains, extending the winter sports season. In addition, kayaking and other water sports are enjoyed year-round, as is hiking — if you embrace the mud like the locals do. Ultimately, we discovered, there’s never a bad time to visit Vancouver.

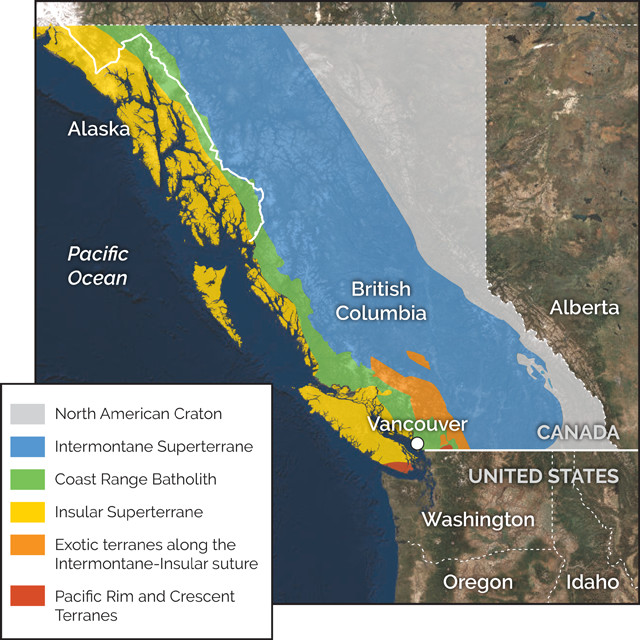

British Columbia’s geologic story starts about 200 million years ago, when the western edge of North America, which had recently separated from the supercontinent Pangea, stood near the modern Alberta–British Columbia border. The land that today makes up British Columbia was subsequently welded onto the continent’s edge in a series of large collisions.

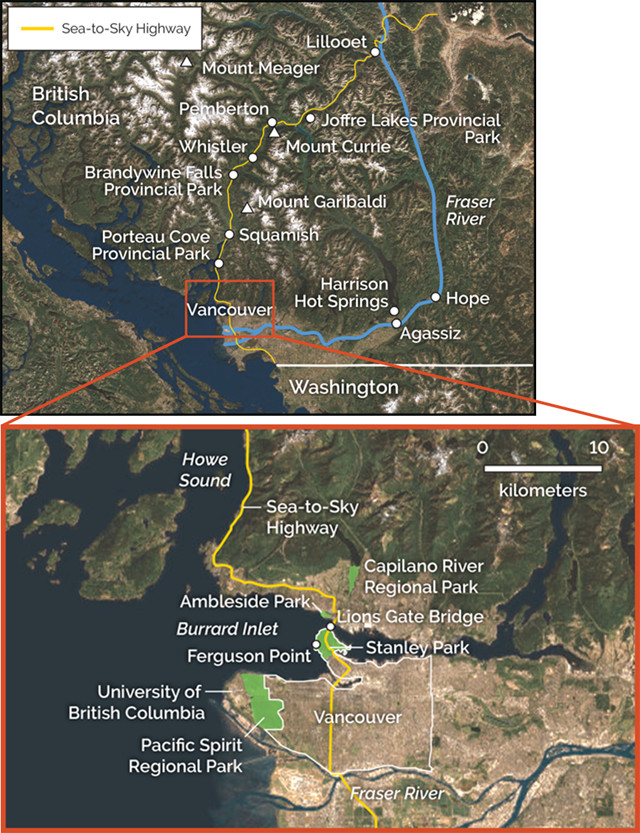

Vancouver sits at the mouth of the Fraser River, the headwaters of which lie in the Canadian Rockies. You'll need a vehicle to drive the entire Sea-to-Sky Highway, but if you remain in Vancouver, you won't need your own wheels; the metro area has an excellent public transportation network. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

While Pangea continued to split apart, North America migrated northwest, creating a long-lived subduction zone where oceanic crust slowly sank beneath the continent’s west coast. This subduction inexorably brought two chains of volcanic islands, the Stikine and Quesnellia arcs, which had each formed near proto-Asia, closer and closer to North America. And about 180 million years ago, the buoyant continental crust of the arcs collided with North America. Because these “exotic” rocks host fossil species that more closely resemble those found in contemporaneous Asian rocks than organisms native to North America, geologists call these crustal fragments tectonostratigraphic terranes (or “terranes” for short). In about 1980, geologists developed the concept of exotic terranes to explain the dramatic differences in rock and fossil assemblages they found in the many fault-bounded blocks that extend from British Columbia to Northern California.

Because the Stikine and Quesnellia terranes welded to North America at almost the same time, geologists group them, along with two additional terranes composed of exotic oceanic material that were caught up in the collision as well, as the Intermontane Superterrane, which today forms eastern British Columbia. Despite the force of this collision, it did not halt the continent’s northwestward drift, and history soon repeated itself. A new subduction zone formed along the continent’s western edge, and between 120 million and 100 million years ago, more exotic material, known as the Insular Superterrane, collided with the first superterrane, appending what’s now western British Columbia (as well as chunks of Yukon and Alaska) onto North America.

After exploring Vancouver, we embarked upon a 500-kilometer driving loop to tour the diverse and spectacular topography that’s been carved from this collection of exotic rocks — and to explore available mud season activities. Our route led northeastward through the mountains of the Coast Range to Lillooet, then turned south and west to return to the city along the Fraser River, which winds through a handful of small exotic terranes wedged along the suture between the Intermontane and Insular superterranes.

British Columbia is composed of a portion of the ancestral North American Craton as well as two superterranes that were appended to the continent during a pair of Mesozoic collision events. The Coast Range Batholith intruded into the Insular Superterrane about 100 million years ago. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

The city of Vancouver sits at the mouth of the mighty Fraser River, the headwaters of which lie in the Canadian Rockies near the Alberta border. The Fraser drains a quarter of British Columbia, producing an annual discharge of about 112 cubic kilometers, the largest Canadian river that empties into the Pacific. It deposits 20 million tons of sediment a year in its delta, which has created the comparatively wide strip of flat land that hosts southwestern British Columbia’s many productive farms and some of Vancouver’s suburbs. The city proper is built on slightly higher ground veneered by glacial till. At the peak of the last glacial episode 18,000 years ago, Vancouver was entombed under 2 kilometers of ice. The till was deposited as those glaciers began their retreat.

Situated between the delta and the Coast Range, Vancouver is an outdoor playground that offers the rare opportunity to sea kayak in the morning and ski that afternoon. Excellent scuba diving spots — many accessible from shore — are found within 20 minutes of downtown, and orca and humpback whale-watching tours depart daily from April through October. Three ski areas lie within a 30-minute drive, and the nearby Capilano River Regional Park offers riverside hiking trails where you can watch salmon swim up a fish ladder during the October and November Chinook spawning season. There’s also great hiking within the city limits, including rainforest walks in Pacific Spirit Regional Park adjacent to the University of British Columbia campus and in Stanley Park, which occupies a peninsula at the mouth of Burrard Inlet, the site of the city’s main port.

Siwash Rock is a sea stack in Stanley Park carved by waves from resistant Oligocene basalt. Credit: Fawcett5, public domain.

The best way to glimpse Vancouver’s bedrock is by strolling or biking along Stanley Park’s 8.5-kilometer-long seawall trail. The best bedrock exposures lie along the 2.5-kilometer section between Ferguson Point and Lions Gate Bridge. Ferguson Point’s seacliffs consist of 40-million-year-old sandstones belonging to the Nanaimo Group. Because these rock layers tilt gently southward, the sandstones become progressively older as you walk north toward the bridge. The Nanaimo Group sediments were eroded from the mountain range that rose in response to the collision of the Insular Superterrane with North America. Siwash Rock, a scenic sea stack about a kilometer north of Ferguson Point, and Prospect Point, located next to the bridge, are both basalt dikes that intruded the sandstone about 31.5 million years ago. This volcanic activity was associated with the initiation of the modern Cascadia Subduction Zone (CSZ) beneath the west coast — the third subduction zone to form in 180 million years. If the weather cooperates, you can extend your hike by strolling across Lions Gate Bridge and through Ambleside Park in West Vancouver on the opposite side of Burrard Inlet. From there, the view back across Stanley Park of Vancouver’s port and downtown is magnificent.

The journey along the spectacular Sea-to-Sky Highway from Vancouver to Whistler is not to be missed. The two-hour drive, much of which follows the eastern shore of Howe Sound, North America’s southernmost fjord, highlights southwestern British Columbia’s breathtaking scenery and diverse geology, including 11 geologic points of interest described in Natural Resources Canada’s Sea-to-Sky GeoTour.

Vancouver, British Columbia, is nestled between the sea and the spectacular mountains of the Coast Range. Credit: pauldclarke/istockphoto.com.

During the last ice age, Howe Sound was filled with a 2-kilometer-at excavated the land beneath it far blevel. As the sea rose after the last glacial episode, the valley’s lower reaches were drowned, forming a fjord. The forest-clad mountains that rise steeply above the road make for beautiful views, but the large number of debris flows, rockfalls and floods that occur here provide an ongoing challenge for geological engineers tasked with keeping the road open.

Along the drive, the boat dock at Porteau Cove Provincial Park offers unobstructed views of the sound. Like most fjords, which form in steep-sided, U-shaped glacial valleys, the waters of Howe Sound in most places are tens of meters deep just a stone’s throw from shore. But because Porteau Cove straddles the terminal moraine of this area’s last glacier, which today forms an underwater ridge stretching from one side of the sound to the other, the water here is much shallower. This unusually shallow seafloor, which hosts an artificial reef formed by the intentional sinking of a small ship, makes Porteau Cove a favorite of Vancouver scuba divers.

Continuing north on the Sea-to-Sky Highway brings you to a scenic overlook that provides a panoramic view of Squamish, the town at the head of the sound, with Mount Garibaldi looming in the distance to the northeast. Although Garibaldi is part of the same chain of volcanoes formed by the CSZ as Mounts Rainier, Hood, St. Helens and Baker, it lacks those mountains’ conical symmetry. That’s because an eruption at Garibaldi 13,000 years ago built part of the mountain atop glacial ice. Later melting of this ice undermined Garibaldi’s west flank, triggering massive landslides that produced the cliff visible from this vantage.

From this spot, you can also see Stawamus Chief, a tall, forested mountain in the foreground to the right of Squamish and Mount Garibaldi. Its sheer, 700-meter-tall granite cliff is one of the biggest granite climbing cliffs outside of California’s Yosemite Valley. The rock that lines Howe Sound belongs to the Coast Range Batholith, a granite batholith even bigger than California’s Sierra Nevada Batholith, the hard, erosion-resistant rocks of which Yosemite’s grand scenery is made. The comparison is apt because both batholiths are products of Cretaceous subduction along North America’s west coast; the Coast Range Batholith intruded into the Insular Superterrane about 100 million years ago.

A particularly good all-he steep, 7-kilometer ascent to the top of Stawamus Chief. If you prefer a shorter excursion, you can instead visit 335-meter-tall Shannon Falls, British Columbia’s third-tallest waterfall, which is a 200-meter stroll from the road. Its crystal-clear waters tumble down from a valley carved by a smaller, tributary glacier. After the ice melted away, the tributary valley’s floor was left hanging high above the much more deeply eroded sound, producing this beautiful sight.

From atop Stawamus Chief, you can see the popular rock-climbing cliff composed of gray granite, as well as the town of Squamish, British Columbia. In the distance lies snow-capped Mount Garibaldi, part of the Cascade volcanic arc. Credit: GoToVan, CC BY 2.0.

At Squamish, the Se leaves Howe Sound and follows the tributary valley of the Cheakamus River. Although most of the rock lining the highway is granite from the Coast Range Batholith, about 40 kilometers north of Squamish you’ll also start seeing interspersed columnar basalts that are remnants of several Late Pleistocene lava flows. Near Daisy Lake, we discovered another excellent all-season hike: a kilometer-long walk to Brandywine Falls, which takes an elegant 70-meter dive off a stack of basalt flows.

“Because our son is an avid skier, we spent a day of our college reconnaissance tour assessing the area’s downhill offerings at Whistler Mountain, North America’s largest ski resort and the venue for the 2010 Olympic alpine ski races. Even if you’re not a skier, it’s worth riding the year-round Whistler gondola up to the Roundhouse Lodge at 1,850 meters elevation to enjoy the sweeping views. The Black Tusk, a crumbling, horn-shaped rock that once formed the throat of a Cascadia volcano, is particularly noteworthy amid the striking panorama. Erosion removed the volcanic cone that previously enveloped the tusk, leaving behind the more resistant rock of the magma conduit.

Heading north through the Coast Range from Whistler toward the quiet logging and potato-farming town of Pemberton, we continued to traverse more granite that had been injected into the Insular Superterrane. Near Pemberton, however, the granite slowly gave way to sedimentary rocks belonging to the Cadwallader Terrane, a small exotic terrane sandwiched between the two superterranes. According to paleomagnetic evidence, the Cadwallader rocks formed during the Mesozoic at the latitude of present-day Mexico, then subsequently slid north to their present position in British Columbia. This dramatic repositioning illustrates how strike-slip motion, akin to that occurring today along California’s San Andreas Fault, has been an important component of the tectonic activity along North America’s western margin for the last 200 million years.

Pemberton’s dramatic setting is highlighted by the snow-capped summit of Mount Currie soaring nearly 2,400 meters above the town. And just 65 kilometers farther upstream along the Lillooet River, Mount Meager, the northernmost volcano of the CSZ, rises at the head of a tributary valley. In 2010, Meager’s second summit collapsed, producing the largest recorded rock avalanche in Canadian history. The landslide traveled 12.7 kilometers and dammed Meager Creek, creating a 1.5-kilometer-long lake and forcing authorities to evacuate Pemberton due to fears that the landslide dam could catastrophically fail. Fortunately, the lake drained slowly and no flood ever materialized.

From Pemberton, the highway climbs steeply up to Joffre Lakes Provincial Park, which protects one of British Columbia’s most accessible alpine valleys. A 5-kilometer-long trail ascends this valley, passing three turquoise-colored glacial lakes en route. The valley was blanketed by snow when we visited, and we hadn’t brought snowshoes, so we skipped the full hike. But the 500-meter trail to the first lake was passable and provided alpine solitude and a beautiful view of Matier Glacier.

Continuing up the road, we reached the small town of Lillooet, located in the Fraser River Canyon, 100 kilometers northeast of Pemberton. The canyon lies in the rain shadow cast by the Coast Mountains to the west; during our drive, the vegetation along the roadside transitioned from moisture-loving hemlocks, cedars and firs closer to the coast, to ponderosa pines and even sagebrush in the Fraser Canyon. The dryness here gives the landscape quite a different feel from the wetter coast.

From Lillooet we turned south, traversing Fraser Canyon on British Columbia Highway 12, to complete our loop. The river’s southward course between Lillooet and Hope lies along the suture zone of the Intermontane and Insular superterranes, weaving in and out of rocks belonging to the several small exotic terranes wedged between them. At Hope, the river swings westward, then reaches the head of its delta 30 kilometers downstream at the town of Agassiz.

We decided that a fitting finale to our British Columbia adventure would be a soak in nearby Harrison Hot Springs, on the scenic shores of glacial Harrison Lake. The hot springs are the product of continuing subduction-related volcanism, and rocks belonging to a hodgepodge of three different terranes surround the lake, making this an ideal place for our son to contemplate his college choice, and for all of us to reflect on the region’s long history of terrane collisions, glaciation and volcanic activity, whose convergence has produced such magnificent scenery.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.