by Lucas Joel Friday, June 17, 2016

View of Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore along Lake Michigan, as seen from the end of the Empire Bluff Trail. South Manitou Island can be seen in the distance. Credit: National Park Service.

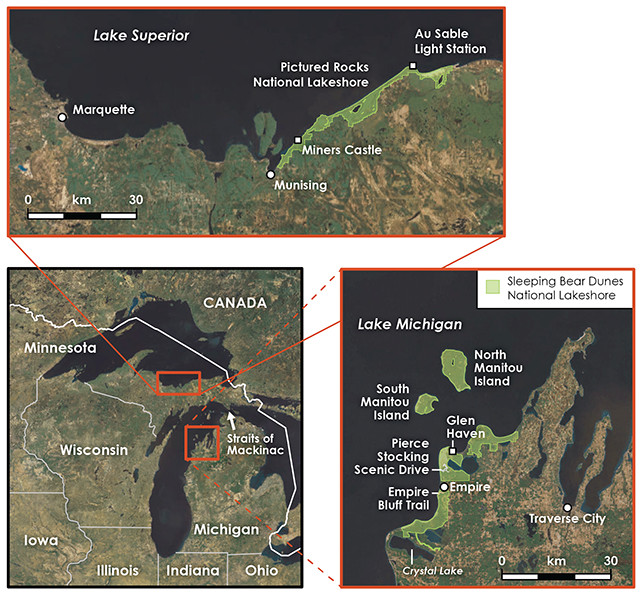

Two of the U.S.'s four national lakeshores are in Michigan: Sleeping Bear Dunes and Pictured Rocks. Credit: all: K. Cantner, AGI.

Empire Bluff trailhead at Sleeping Bear Dunes. Credit: National Park Service.

During the Pleistocene, the Laurentide Ice Sheet, which covered much of North America, gouged large valleys that would one day become the Great Lakes. Today, four of these lakes border Michigan, giving the state’s Lower Peninsula its famed mitten shape and setting much of the Upper Peninsula off on its own. The ice sheet no longer exists, but travelers can visit scenic spots in Michigan — along the mitten’s edges and in its distant provinces — that only came to be because of the ice sheet’s erosive work. Among them are two of the country’s four U.S. national lakeshores, which are managed by the National Park Service: Sleeping Bear Dunes and Pictured Rocks.

Sleeping Bear Dunes, in the northwestern corner of the Lower Peninsula along Lake Michigan, contains large, geologically young sand dunes formed from sediment eroded and deposited by the ice sheet.

Meanwhile, although the rocks in the multicolored cliffs at Pictured Rocks, in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula on the shores of Lake Superior, were also sculpted by the ice sheet, they are much more ancient, dating to the Late Precambrian and Cambrian.

Visiting these two lakeshores offers a distinctive geological time-traveling opportunity: Going from Sleeping Bear Dunes to Pictured Rocks, you can witness the impacts of a single ice age on locales separated in time by more than 500 million years. At both, you will find yourself standing on ground once covered by a 3-kilometer-thick glacier that drastically reshaped the landscape and created the largest system of freshwater lakes in the world.

The northern lights as seen from Sleeping Bear Dunes. Credit: National Park Service.

View of Lake Michigan from Pierce Stocking Scenic Drive at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. Credit: National Park Service.

Lake Michigan Overlook at Sleeping Bear Dunes. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/RiverNorthPhotography.

Several large ice lobes extended south from the Laurentide Ice Sheet in the Pleistocene, between 2.6 million and 11,000 years ago. Two of these lobes — the Superior lobe and the Michigan lobe — expanded into and carved out low-lying, river-incised valleys that became Lake Superior and Lake Michigan. After it came and went, the Michigan ice lobe left behind glacial sediment in the form of ridges, or moraines, in the area of Sleeping Bear Dunes. Imagine a plow pushing material to both sides — that is about how the moraines formed.

The Empire Bluff Trail just south of Empire, Mich., offers a short, though rewarding hike through the glacial history recorded at the lakeshore. Before setting out, pick up a trail map brochure at the trailhead off Wilco Road — it has extra information about what you will see along the way.

The 2.4-kilometer round-trip hike on the trail is hilly and forested, and along the way there are great views of the coast of Lake Michigan, including glimpses of the area’s namesake dunes to the north and a picturesque inland lake called South Bar Lake. Eventually you will arrive at the edge of Lake Michigan atop a sandy bluff, which drops about 120 meters to the lake’s edge. Here, you are standing on one of the moraines left behind by the Michigan ice lobe — one that has been subjected to weathering and erosion from Lake Michigan’s waves, which have helped truncate the moraine, forming the steep drop.

he end of the Empire Bluff Trail, South Manitou Island is visible on clear days. In the summer, you can reach the island, as well as the adjacent North Manitou Island, by boat; both are part of the national lakeshore. These two islands are part of an island chain in Lake Michigan that extends north toward the Straits of Mackinac (pronounced Mack-in-aw), where the Mackinac Bridge connects Michigan’s Upper and Lower Peninsulas. These islands are exposures of Michigan’s bedrock — specifically the limestone of the Middle Devonian Dundee Formation — but they also play a role in the Native American legend that gives Sleeping Bear Dunes its name (see sidebar). Michigan’s bedrock, underlying the state’s glacially scoured landscape, forms the Michigan Basin. Jurassic-aged rocks are at the center of the basin, while the ages of concentric bands surrounding the center extend back into the Precambrian.

Indian Head Point at Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore. Note the different rock colors in the alcove due to mineral staining. Credit: Veryhuman, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Miners Castle is a headland weathered into a shape that resembles a turret from a medieval castle. Credit: Gregg Bruff/NPS photo.

“, about a 10-minute drive north from Empire. These dunes are “perched”: waves and wind weather the coastal bluffs, and the loosened sand is blown high atop the bluffs, forming the dunes. Climbing the dunes — and then trekking down the other side about 120 meters to the water’s edge — gives a sense of the large-scale aeolian erosion and deposition occurring here. The dunes perch atop the Sleeping Bear Plateau, roughly 8 kilometers long and 5 kilometers wide; if you summit the first dune at the Dune Climb, you will still have 2.8 kilometers to hike across the sands before you reach Lake Michigan.

“In winter, watching falling snowflakes at the dunes is an informative — albeit cold — way to see the local wind patterns at work and how they shape the dunes. When I visited in January 2016 it was windy and snowing. On one dune’s windward slope, facing the lake, snowflakes blew horizontally at the dune’s crest. After cresting, the flakes fluttered downhill and settled on the dune’s leeward slope, just as windblown sand grains might.

" — you’re [high] above the lake on a big sand dune, you’re looking out on Lake Michigan, and it’s jaw-droppingly beautiful.”

“From Lake Michigan Overlook, you can also catch a glimpse of the lakeshore’s eponymous Sleeping Bear, which is a dune that was once bear-shaped. “The Native American tribes in the area used it as a navigational mark,” Baughman explains. “But it’s disappearing, and it’s hard to know how much longer it’ll last. As the dune advances east, it’s getting eroded quite a bit.”

png” caption=“Miners Falls, as viewed from the end of Miners Falls Trail. Credit: National Park Service.” >}}

Mineral-stained cliff face at Pictured Rocks. Credit: National Park Service.

ce at Pictured Rocks. Credit: National Park Service.[/caption]

chigan’s glacial history lies in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula about a five-hour drive from Sleeping Bear Dunes. From Traverse City, going north, you cross the 8-kilometer-long Mackinac Bridge, which serves as a symbolic boundary between Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. In winter, both lakes can be completely frozen over, and winds can be fierce while driving across the bridge. Traveling north, you are slowly making your way back in time as you head down-section through the Michigan Basin, to its outermost and oldest fringes, which you can see at scenic Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore.

In summer at Pictured Rocks, waterfalls cascade over many lakeside cliffs into Lake Superior. Tucked within the sandstone cliffs, which extend along the coastline for 24 kilometers, are also natural arches and sea caves. On some cliff faces, mineral stains — including red and orange from iron, blue from copper, white from limonite, and brown and black from manganese — mingle to form what looks like abstract artwork. The stained rock inspired the lakeshore’s name, and the best place to view the mineral stains from land is at Miners Castle. Miners Castle, a headland weathered into a shape that resembles a turret from a medieval castle, is a short drive from the area’s largest town, Munising. Here, the cliffs emerge straight from the water, and, in places, preserve sea caves. Taking a boat into Lake Superior may be the best way to see these features head-on, but the waters in Lake Superior can be rough and treacherous, so make sure to brush up on your seafaring safety know-how before embarking.

Before you get to Miners Castle, turn right onto Miners Falls Road from Miners Castle Road to reach a trail that leads straight to one of the lakeshore’s many waterfalls. The 1-kilometer hike is wooded, and mostly over flat ground until you reach a set of stairs that lead down to the waterfall, which flows over an outcrop of the lakeshore’s Cambrian sandstone bedrock. The falls form from the north-flowing Miners River, which, before reaching the waterfall, flows over the relatively hard sandstone of the Au Train Formation. Below the Au Train sits the soft Miners Castle Member of the Munising Formation, which erodes more easily than the Au Train Formation.

This style of waterfall formation — where water erodes soft rock sitting below harder rock, forming a vertical drop-off — is common throughout the lakeshore. The lakeshore’s waterfalls gush in warmer months, but freeze in the winter. The frozen falls, including Miners Falls, are breathtaking. If you go in the winter, drive along Sand Point Road just north of Munising, and park at Sand Point Beach. You will then need to hike back along the road; there are few marked trails, so hike into the woods above the lake when you spot an obvious path forward. You will not have to hike far before reaching a long stretch of cliff, which has frozen falls hanging from it along almost its entire length; this area is known as “The Curtains,” and for good reason.

When you get to Miners Castle after hiking to the falls, there are many trails and overlooks from which the colorful medleys upon the cliff faces — as well as sweeping views of Lake Superior — can be seen. The visible rock layers, which dip gently to the south, are some of the bottommost layers of the Michigan Basin: If you want to take a peek into the Late Precambrian, head northeast to Au Sable Light Station, where deep red sandstone can be found near the old lighthouse.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.