by Callan Bentley Tuesday, December 27, 2016

A typical view of the countryside of the Shetland Islands. Credit: Callan Bentley.

About 170 kilometers northeast of mainland Scotland, there is a remote cluster of islands featuring terrific geology, friendly people, an idiosyncratic landscape, and a great many sheep. This is Scotland’s Shetland Islands, an archipelago known to its friends as simply “Shetland.”

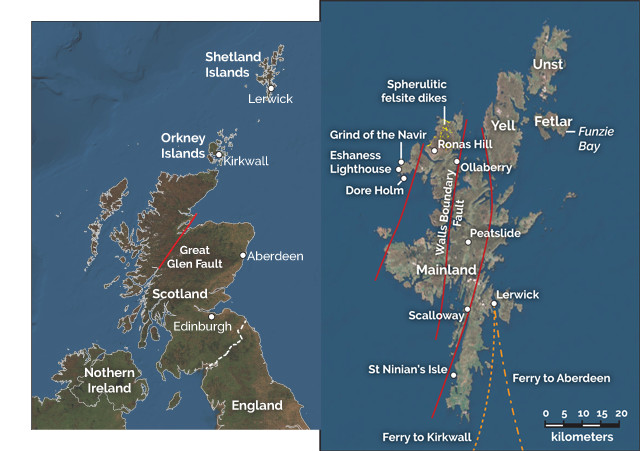

Shetland, about 170 kilometers northeast of mainland Scotland, comprises about 100 islands, about 15 of which are inhabited. Getting around them involves cars and ferries. Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI.

Geologic highlights amid the islands include the northernmost trace of the Great Glen Fault, which slices prominently through mainland Scotland; world-class displays of coastal landforms and coal-forming processes; a wealth of flooded valleys that make for fascinating drives through labyrinthine Shetland; a Devonian volcanic center; extraordinary ceremonial stone axes with “eyes”; an ophiolite complex; and, most exciting to me, the beach where strain in a metaconglomerate rock was first quantified. The islands offer a different view around every corner, and there are a lot of corners!

Ancient circular stone buildings called brochs can be seen in and around Lerwick. Credit: Callan Bentley.

“At the museum, you’ll also learn about the critical role Shetland played during World War II as the site of a clandestine boat system (“the Shetland Bus”) that transferred information and personnel for the Allies between Scotland and German-occupied Norway, as well as about how Edmund Hillary wore Shetland wool on his 1953 ascent of Mount Everest. Not far from Lerwick, the Scalloway Museum in the town of the same name is also worth visiting if you’re interested in learning even more about Shetland’s history. Next door to the museum is a bonus for visitors: the remains of the impressive Scalloway Castle, built in 1600. If you’re interested in a walk through the castle, just ask to borrow the key at the museum.

“While you won’t find a bit of homegrown coal in Shetland, almost everywhere you look, you’ll see peat, the spongy plant matter that is the progenitor of coal. Coal is unusual among sedimentary rocks in that it contains no mineral matter, consisting instead of organic carbon. When we burn coal, we are releasing energy originally captured through ancient photosynthesis. In Shetland, you can get a sense of how that capture played out in the peat.

Shetlanders hack off chunks of peat from hillsides for fuel and stack them in geometric piles to dry. Credit: Callan Bentley.

I came to Shetland with a naive idea about how peat accumulates, thinking it was solely in low-lying “swampy” areas. The reality is actually more interesting. In Shetland, the damp weather means that sphagnum and heather, the main peat-building vegetation, grow on slopes and hilltops as well as in the valley bottoms, with underlying peat layers averaging 1.5 meters in thickness. Regardless of topography, the entire landscape is essentially blanketed in bog. When harvesting peat for fuel, a Shetlander hacks away at a vertical wall cut into the peat, slabbing off small bricks the size of bread loaves. These are stacked in geometric piles with lots of air-flow for efficient drying. As the active face of a peat quarry is mined and retreats, the green vegetation carpeting the top is removed with care and replanted atop ground where the quarriers have already mined. There, it begins growing anew. Plenty of rain and a mild climate — thanks to the Gulf Stream, it almost never snows in Shetland — allow about 1 centimeter of new peat to accumulate beneath the green each year. By the time a century has passed, there’s a lot of new peat available — it’s a renewable resource. If there is sufficient rain to make it soggy and weak, peat growing on hillsides can slough off and rush downhill in a “peatslide.” When this happens, the bedrock beneath is revealed. And my, what excellent bedrock it is.

“The bedrock in Shetland is mainly a mix of igneous rocks erupted during the Caledonian Orogeny between 490 million and 390 million years ago, combined with 800-million- to 500-million-year-old Neoproterozoic metasediments, which include a package of carbonates near Scalloway that have been chemostratigraphically correlated with “Snowball Earth” cap carbonates elsewhere around the world. Also present are Archean gneisses of the Lewisian Complex, metamorphic rocks prominent in northwest Scotland that are the oldest in the United Kingdom. The reason so many different rocks are clustered in such a small location is that a series of north-trending transform faults have jostled rocks of vastly different ages and lithologies into neighboring positions.

A series of north-trending transform faults have moved rocks of vastly different ages and lithologies into neighboring positions. The best place to see this is on the Ollaberry Peninsula. Credit: all: Callan Bentley.

“The best place to see this juxtaposition is the beach at Ollaberry, situated on the northern part of Mainland, called Northmavine, where the Walls Boundary Fault crops out. The fault is interpreted as the northernmost strand of the Great Glen Fault, which is famous farther south for its decisive strike north-northeast through mainland Scotland, and for the fact that its linear belt of crushed-up rock has been etched out by glaciers and rivers into a series of long, skinny lakes, Loch Ness among them. At Ollaberry, there is a wall of granite on one side of the fault, and a beach backed by tightly folded metamorphic rocks on the other. It’s a great place to visit, hiking in across the peninsula along the subtle trace of the fault, only to have the land suddenly drop away to a beach exposing the “guts” of the fault. The folded phyllites and quartzites vary between big elephantine loops and tight geometric kinks. Next door, a massive wall of granite looms high above, undeformed and unperturbed.

Exploiting and transecting these faults are “voes.” “Voe” is a term used in both Shetland and the Orkney Islands for a narrow inlet. It’s a flooded valley like a fjord, but fluvial rather than glacial in origin. The voes of Shetland are numerous and twisty, resulting in the islands’ incredible coastline-to-landmass ratio. This makes driving in Shetland tricky: Getting from point A to point B might take hours along a very indirect route. An inexpensive municipal ferry service makes island hopping feasible. Many of the voes host salmon and mussel farms. Aquaculture is booming in Shetland, and locally grown seafood is available in many restaurants.

A great example of a tombolo, a deposit of sediment connecting a bedrock island to the mainland, can be seen at St. Ninian's Isle. Credit: Callan Bentley.

The Grind of the Navir, a difficult-to-access gate-like natural rock notch, looks like something out of Middle Earth. The name means “gate of the borer.” The grind admits strong waves only during intense storms. The waves climb 15 meters up a stone ramp and pound through the grind to blast at the rosy ignimbrite at the top. Long-exposed rock weathers to black, but the freshest stuff is as pink as fresh salmon. Huge slab-like boulders have been piled up at the back of a scoured-out amphitheater. Technically, this pile of boulders qualifies as a “beach” — a storm beach. It’s a mind-blowing experience to walk through the grind and imagine how powerful a storm would have to be for the sea to rip boulders off a wall 15 meters above sea level.

Finding the grind will be easier if you hire a guide, but you’re welcome to try on your own too. Shetland follows the Scottish Outdoor Access Code, which means that people have the right to responsibly access any land in the country; there is no such thing as trespassing. Seacliff-top walking paths wrap around the coastline, regardless of who owns the property locally, and that’s a great way to access places like the Grind of the Navir. Just be sure to have a copy of the relevant Ordnance Survey maps for the area you wish to explore.

“The ignimbrite at the grind is Late Devonian in age, roughly 394 million to 384 million years old, and it’s one of the many igneous rocks of that age in Shetland. Others include the lurid pink granite of Ronas Hill, Shetland’s highest point, but also the basalt and mafic agglomerate at Eshaness on the west side of Mainland. At the Eshaness lighthouse, one can view foreboding black cliffs, as well as a suite of diverse volcanic textures that reveal the guts of an ancient stratovolcano like modern Mount Rainier, though the inferred original conical shape has long since been eroded away. Eshaness’ marine terrace is also dotted with a selection of glacial erratics. Just south of Eshaness is the photogenic sea-arch island, Dore Holm (“Door Island”).

The Devonian-aged dikes at Northmavine are composed of spherulitic felsite, a granitic intrusive rock with hailstone-shaped orbs inside. Credit: both: Callan Bentley.

Neolithic Shetland residents used this distinctive rock to craft thin ceremonial axes or knives, polishing them with sand until they were glossy smooth. These were apparently objects of ritual and beauty rather than utilitarian tools. As artifacts, they are visually striking, but geologically they’re interesting too.

Funzie Bay on the island of Fetlar is where structural geologist Derek Flinn developed his "Flinn diagram," which allows geologists to quantify the strain on cobbles in a metaconglomerate. Credit: Callan Bentley.

“In 2009, the European Geoparks Network certified the whole archipelago of Shetland as a geopark, based on its unique and notable natural heritage. A series of interpretive resources may be found online, and artistic rock walls and interpretive signage grace many of the most important sites — including, for me, the island of Fetlar.

The story told by a metaconglomerate — a former sedimentary rock made of pebbles and cobbles that's been smeared out by high temperatures and pressures — is of energetic depositional conditions prior to lithification, followed by the rock being heated and squished. Credit: Callan Bentley.

Fetlar was a place of pilgrimage for me as a structural geologist: The beach at Funzie Bay (pronounced “Finney”) was where structural geologist Derek Flinn developed a novel technique for quantifying the strain on cobbles in a metaconglomerate, a former sedimentary rock made of pebbles and cobbles that’s been smeared out by high temperatures and pressures. The story a metaconglomerate tells is of energetic depositional conditions prior to lithification, followed by the rock being heated and squished. But how exactly it was squished — like a stress/strain steamroller that pancakes the rocks, or more like a tectonic toothpaste tube that pushes out more cigar-shaped cobbles — was an enduring mystery for geologists.

Flinn found that by measuring the dimensions of oblong cobbles in metaconglomerates and plotting ratios of these dimensions to one another, he could efficiently plot the shapes of the cobbles — flat like pancakes or stretched out like cigars, for example — and get a sense of the tectonic conditions that caused the cobbles to deform. Ever since Flinn published his method in 1962, the eponymous Flinn diagram has been used to denote the shape of strain ellipsoids, an easy way to map out the structural “grain” of the rocks. It’s a way of saying whether the grains in the deformed rock are more like a handful of pencils, a school of fish or a pile of neglected term papers on a professor’s desk.

“Wherever in Shetland you choose to explore, you’ll find much to enjoy in this stunning landscape of both geological and historical significance.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.