by Terri Cook and Lon Abbott Tuesday, June 5, 2018

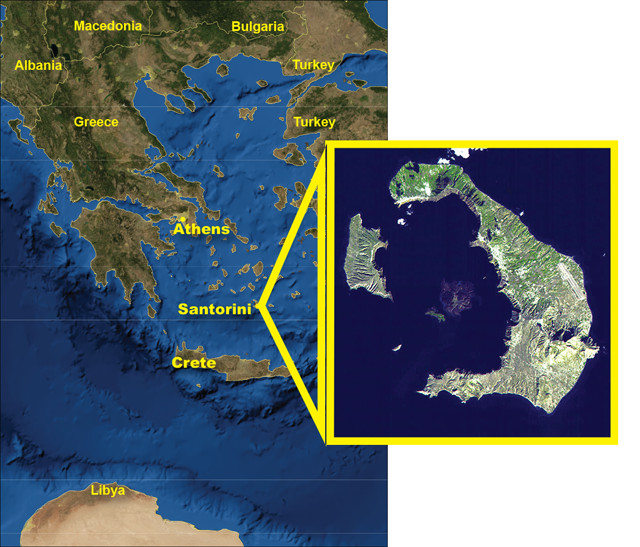

Santorini is an idyllic Greek isle renowned for its sensational sunsets, colorful beaches, and blue-domed, whitewashed buildings clinging to sheer, dark cliffs. Located in the Aegean Sea, this unique destination is part of a circular archipelago of volcanic islands that were joined together in a single land mass until about 1600 B.C., when it was ripped apart in one of the largest volcanic eruptions in recorded history.

Santorini is the largest in a ring of islands ripped apart in one of the largest volcanic eruptions in recorded history. Credit: AGI/NASA; middle: NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS and US/Japan ASTER Science Team

Santorini’s “Big One” occurred during the Late Bronze Age, at the height of the Minoan civilization, which dominated the region from 2000 to 1450 B.C. This so-called “Minoan eruption” shattered the volcano, causing the central portion to collapse below sea level and leaving a series of islands with dramatic cliffs ringing the protected central bay. The largest island is commonly called Santorini (but is officially known as Thera). The eruption, which discharged about 30 cubic kilometers of volcanic material and spread ash across a large portion of the eastern Mediterranean, is also thought to have unleashed a giant tsunami that devastated the island of Crete, the center of Minoan civilization, 140 kilometers to the south. Some scholars hypothesize that this calamity inspired Plato’s story of the lost city of Atlantis; the thriving Minoan city of Akrotiri, on southern Santorini, was buried under a thick pile of ash, preserving it in much the same way as the eruption of Vesuvius did Pompeii in Italy. Excavations begun in the 1960s have unearthed part of a large town with three-story buildings, streets and squares. Discoveries of stunning frescoes, huge ceramic storage jars called pithoi, and sophisticated masonry all indicate that Akrotiri was once a major Bronze Age port with a flourishing economy supported by extensive trade across the eastern Mediterranean Sea.

Today, you can explore the island’s fiery history, the artifacts of Akrotiri, the ruins of another ancient city, called Thira, and modern volcanic features — as well as relax on the beach, feast on Greek specialties, and sip local wine reaped from the fertile volcanic soil.

A History of Collapse and Resurgence

Although you can arrive by air, it is most impressive to approach the island by ferry to get a first-hand look at the 300-meter-tall cliffs. As the ship enters the ring of islands, join the crowd rushing to the decks to gaze at layer upon layer of volcanic rock crowned by the whitewashed buildings of several picturesque towns. The lighter volcanic layer immediately below the buildings was ejected during the Minoan eruption.

Artist's conception of the eruption of Santorini in about 1600 B.C. The eruption and an ensuing tsunami are thought to have wiped out the center of the thriving Minoan society on Crete. Credit: ©AGI/Meteor Studios

Santorini did not begin as a volcano. Its basement rocks consist of Mesozoic and Early Cenozoic-aged marble and phyllite. You can see these at the ancient city of Thira, located in the southeast portion of the island. This assortment of Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine ruins is perched on a block of marble that was first settled by the Dorians in the ninth century B.C.

Volcanism began on the island’s southern edge 1.6 million years ago as the product of subduction. South of Crete, the oceanic crust of the African Plate is diving slowly beneath the Aegean Microplate, forming the 500-kilometer-long Hellenic Arc, which encompasses half a dozen historically active volcanoes, including Santorini, which formed on a northeast-trending block of continental crust raised along a fault.

Since volcanism began, a series of major eruptions has built up the thick pile of volcanic deposits that comprise most of today’s island. The nearly vertical cliffs you see from the ferry mark the edge of a caldera — a large basin-shaped depression created by an exceptionally violent volcanic eruption. A caldera forms when a chamber of gas-rich magma begins to work its way up toward the surface directly beneath the volcano. The magma’s high concentration of dissolved gases gradually boosts the pressure inside the chamber until it exceeds the strength of the overlying rock. When the rock ruptures, magma bursts out in a gigantic explosion. As the largest and most violent type of volcanic eruption, caldera eruptions empty the entire magma chamber in a matter of days or weeks, creating a subterranean void that cannot support the weight of the volcano above. The mountain collapses into the cavity, leaving a giant depression — a caldera — in its stead.

Although the Minoan eruption is the most famous, Santorini has actually witnessed at least four such caldera eruptions, with the Minoan being the most recent. The caldera wall you cruise beneath today is a complex assemblage of cliff faces of different ages that have been exposed and re-exposed by this sequence of explosions. Volcanism on the island’s southern edge ceased about 500,000 years ago, when activity shifted northward. There, frequent eruptions built up a pile of overlapping lava shields and volcanic cones that repeatedly collapsed, at times allowing the sea to inundate. Subsequent landslides, wave erosion and weathering have also helped to sculpt the masterpiece you see today. Geologists attribute this cyclic history to the existence of a long-lived magma plumbing system focused along the same deep, northeast-to-southwest trending fracture that raised the basement marble visible at Thira.

Akrotiri: The Greek Pompeii

Only a small portion of the town, which may have covered tens of hectares, has been excavated to date, but the finds are remarkable. The buildings display excellent masonry and hosted beautiful frescoes, some of which are on display at Phira’s Museum of Prehistoric Thera. Along with decorated pottery and carefully crafted metal utensils and weapons, archaeologists have also discovered a loom workshop beneath the ash, suggesting that textiles were an export. The town had a sophisticated drainage system, pipes with running water, and even flush toilets. The pipes ran in twin systems, indicating that the Minoans had both hot and cold running water; the hot water may have been geothermally heated.

Unlike at Pompeii, the excavations have yielded no evidence of human remains and few valuables, suggesting that the inhabitants had warning of the impending disaster. While archaeologists toil to reconstruct this ancient Minoan city, geologists are working to reconstruct what the Bronze Age island must have looked like. Most think that it was roughly horseshoe-shaped with a large, shallow, flooded caldera in the center. This depression formed about 21,000 years ago following an earlier caldera eruption. The sheltered bowl, which most likely hosted an island, would have provided an excellent harbor for the Minoans, protecting their vessels from the region’s strong winds. Thus, the same long-lived volcanism that created the harbor and allowed Akrotiri to thrive as a trading center, also eventually destroyed it.

Beaches in Santorini tend to be more rocky than sandy. Credit: Megan Sever

Near Akrotiri, on the island’s southern shore, are two of the most popular beaches: Red Beach and White Beach. Most of Santorini’s beaches feature gray volcanic sand and pebbles, a geologic calling card of the isle’s explosive history. Red Beach, which lies in the center of an eroded cinder cone, is a colorful alternative for soaking up the sun and the scenery. (Beware that the “sand” is sharp and can be painful to walk on; wear proper footwear.) As you wander down Red Beach’s narrow access trail, look for loose cinders scattered across the ground. Peppering many of these are small, rounded holes called vesicles, the remnants of trapped gas bubbles “frozen” in the rock as the erupting lava rapidly cooled and solidified. The lava also contained abundant iron, which rusted in the air, creating the rocks’ red hues. You may also spot wave-rounded pebbles of colorful agate, which forms in cavities in volcanic rocks, along the shore. Nearby White Beach, accessible only by boat or by foot from Red Beach, is surrounded by tall, whitish cliffs of volcanic ash.

Dating the Eruption

The widespread ash deposits from the Minoan eruption are of special interest to archaeologists. With precise dating, the ash layer can act as a marker to accurately date archaeological sites throughout the Eastern Mediterranean, giving archaeologists a snapshot of civilization in the Late Bronze Age.

Although the exact date of the Minoan eruption remains unknown, active scientific research and debate continue. Dates derived from Egypt’s historical chronology suggest a mid-to-late 16th century B.C. timeframe, whereas radiocarbon dates suggest that it occurred a century earlier.

Some effects of the Minoan eruption were felt worldwide, including frost damage to trees in Ireland and the U.S., climate perturbations in China, and ash particles deposited on the Greenland Ice Sheet. Geologists have taken advantage of these effects to develop some ingenious techniques to try to resolve the date of the eruption. One group of researchers used acidity spikes found in Greenland ice cores to date the eruption to 1645 B.C. Another group, using an Irish oak tree-ring chronology that spans more than 7,000 years, determined that the Minoan eruption occurred in 1628 B.C., in good agreement with a study that found decreased tree-ring growth in the U.S. in 1628 to 1626 B.C.

In 2006, scientists announced that they had found the branch of an olive tree they think was buried alive by the Minoan eruption. Radiocarbon dates from the branch’s outermost growth ring place the eruption between 1627 and 1600 B.C. Even more recently, several studies have reported sedimentary evidence of a tsunami that occurred at that time along the coasts of Sicily and Israel, 1,000 kilometers away, adding further credence to an eruption date in the late 17th century B.C. — as well as evidence that the Minoan eruption was a catastrophe for the entire Mediterranean Basin.

Modern Volcanism

Today, two small islands squat in the middle of Santorini’s flooded caldera. Both are the peaks of a lava shield that formed after the Minoan eruption. Called resurgent domes, these points of land are known as the Kameni islands; you can visit them on a pleasant half- to full-day excursion. Nea Kameni, the northern island, is the site of Santorini’s most recent eruption, which occurred in 1950. Although the eruption was comparatively tame, it still shot a column of ash and debris 1,000 meters into the air and spit out Greece’s youngest rocks. Sixty years later, both islands continue to experience ongoing seismic activity. While on the islands, you can visit fresh lava and fumaroles and soak in Palai Kameni’s relaxing hot springs.

Visitors can explore the island of Nea Kameni, part of a resurgent dacite lava shield and the site of Santorini's most recent eruption. At Nea Kameni, visitors can walk on recent lava flows and swim in geothermally heated water. Credit: Megan Sever

Given the ongoing seismic and fumarole activity, another eruption on Santorini is almost inevitable. The historic record suggests that it will be a small event typical of the many that have occurred during the last 2,000 years, but volcanoes are notoriously unpredictable. Despite the fact that geologists consider Santorini one of Europe’s most dangerous volcanoes, no emergency evacuation plan currently exists for the island.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.