by Terri Cook and Lon Abbott Friday, August 31, 2018

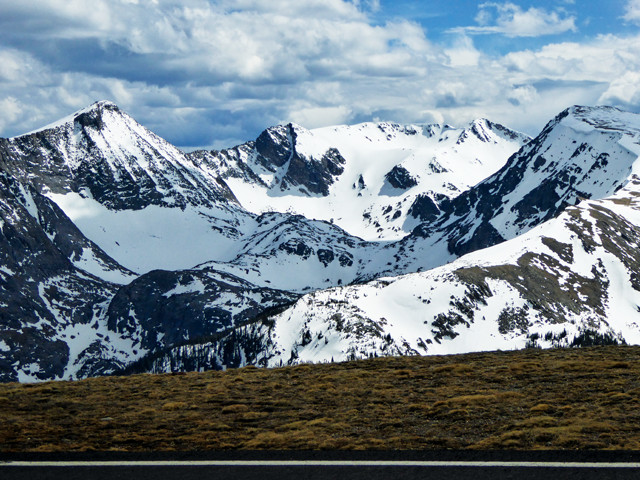

Driving Trail Ridge Road, North America's highest continuously paved highway, immerses you in the grandeur of the Rockies. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

In mid-April each year, two Colorado snow-clearing crews embark upon an assignment with a deceptively simple goal: to traverse the 77-kilometer stretch of road between them and meet at the middle. Armed with front-end loaders, graders and rotary plows, one team starts clearing snow on U.S. 34 in the town of Estes Park, Colo., while the other begins removing it from the same road in Grand Lake, Colo. Working in the lulls between fierce spring storms packing gale-force winds that frequently undo their efforts, the teams arduously ascend nearly 1,200 meters, clearing 3- to 6-meter-high snowdrifts in their path. When, after five to seven weeks, the crews finally come face to face near the crest of the Rockies, their success is heralded because it means that Trail Ridge Road, North America’s highest continuously paved route, is once again open for the summer.

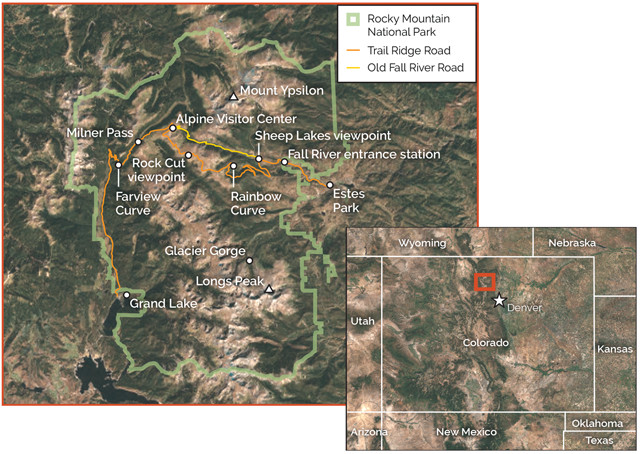

Trail Ridge Road, which reaches an elevation of 3,713 meters, is the only road that crosses Rocky Mountain National Park. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

Trail Ridge Road meets Old Fall River Road, seen here, high above the timberline at the Alpine Visitor Center. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Often dubbed the Highway to the Sky because of its lofty 3,713-meter-high crest, Trail Ridge Road is the signature scenic drive in Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park. The winding ribbon of hairpin bends, each of which offers a fresh vista of soaring, snow-capped peaks, is the only road that crosses the national park and one of the most convenient places in North America to see windswept alpine tundra and the abundant wildlife and colorful carpets of tiny wildflowers it hosts for a few precious weeks each summer. Constructed between 1926 and 1932, Trail Ridge Road was built as an alternative to Old Fall River Road, whose narrow width, constricted bends, and grades up to 16 percent made it difficult for drivers to navigate and whose position in the bottom of a valley caused it to hold so much snow that it was often impassable until mid-summer.

Due to its ridge-top location, Trail Ridge Road receives more sunshine and wind and accumulates less snow than Old Fall River Road, all of which mean Trail Ridge can be opened earlier (and closed later). Once the eastbound and westbound road crews meet up and the weather stabilizes in late spring, the National Park Service (NPS) throws open the gates, allowing drivers to experience for themselves the inspiring scenery that Horace Albright, a former NPS director, once described as “the whole sweep of the Rockies before you in all directions.”

Trail Ridge Road is a great place to look for marmots, bighorn sheep and other hardy wildlife. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

The stunning scenery along Trail Ridge Road represents an interesting dichotomy: While the rocks are among the oldest in Colorado, this landscape has only existed for a geologically short period of time, with the finishing touches placed within just the last 10,000 to 20,000 years. The bedrock in this area comes in two varieties: dark metamorphic gneiss and schist, and the smooth, light gray granite that subsequently intruded the metamorphics.

The gneiss and sch 1.8 billion years ago in the depths of an ancient subduction zone. At that time, in modern geographic coordinates, the southeastern coast of an embryonic North America lay about where the Colorado-Wyoming border exists today. Oceanic lithosphere attached to Wyoming was slowly subducting beneath another oceanic plate to the southeast, creating a chain of volcanic islands similar to today’s Aleutian Islands.

Mount Ypsilon's steep slopes consist of dark metamorphic rocks intruded by younger, light gray granite. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

The motion of glaciers has rounded and polished this granite outcrop, while hard rocks dragged along the ice's base formed the parallel, horizontal grooves known as glacial striations. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

“At the base of the islands, ash and lava erupted from those volcanoes interspersed with layers of sand and mud shed from their slopes, gradually forming a stack thousands of meters thick. The layers were eventually buried deeply enough that heat and pressure metamorphosed them into the foliated rocks now visible in many areas of Rocky Mountain National Park. Meanwhile, subduction slowly dragged Wyoming’s continental crust ever closer to the oceanic trench until, about 1.78 billion years ago, this buoyant continental material collided with the volcanic island chain, appending the young schists and gneisses onto the edge of proto-North America.

About 1.4 billion years ago, enormous volumes of magma welled up beneath modern-day Colorado along this old suture zone and then slowly cooled to form a series of large granite batholiths. One of the biggest is the Longs Peak Batholith, named for the park’s highest peak, which comprises the light gray granite so prevalent throughout the park. The causes of this granite-forming episode, one of the greatest Earth has ever witnessed, remain mysterious and are the subject of current research.

The next chapter ihis region’s geology began just 65 million years ago — after a gap of 1.3 billion years — when the Front Range, the easternmost of several Rocky Mountain ranges, rose thanks to thrusting and folding during an event that geologists call the Laramide Orogeny. After the tectonic fireworks ceased, the Trail Ridge area consisted of a gently rolling upland. It’s unknown how high that upland was, but geologists think the region stood lower than today. It took a second uplift event, this one without the folding and faulting, for it to attain its modern elevation. Heating of the mantle beneath Colorado is the likely cause of the second uplift event, but geologists argue about precisely when it occurred. Some think it was about 40 million years ago, whereas others think it occurred within the last 10 million years.

Regardless of the exact timing, even with the boost to its modern elevation, the Trail Ridge area was still characterized by rolling hills until the onset of the Pleistocene ice ages 2.6 million years ago. During the Pleistocene, the climate fluctuated in response to cyclical changes in the amount of solar energy that Earth received from the sun due to slight changes in the tilt and wobble of Earth’s spin axis combined with small differences in the radius of Earth’s orbit. Glaciers grew when the planet received less solar radiation and retreated when it received more. Each time the ice advanced, it filled the park’s valleys, quarrying enormous blocks from the mountainsides and transforming the once-undulating upland into the ruggedly beautiful and celebrated landscape of today.

The dramatic alpine scenery visible from Estes Park, the eastern gateway to Rocky Mountain National Park, was sculpted during repeated Pleistocene glaciations. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Driving Trail Ridge Road is a highlight of any summer excursion to Rocky Mountain National Park. Along the road, pullouts offer safe places to stop and snap photos, and to enjoy the expansive views and geologic highlights along the way.

Most visitors begin their journey along Trail Ridge Road at the Fall River entrance station, the 2,511-meter-high gateway along U.S. 34 on the park’s eastern side. As you approach the park boundary, the 1.4-billion-year-old Longs Peak Batholith is visible in the canyon carved by the rushing Fall River. By the time you reach the entrance station, this bedrock is veneered with glacial till — debris ranging in size from fine powder to house-sized blocks that was quarried by glaciers, carried down the valley, and dumped when the ice receded. This till was deposited between about 200,000 and 130,000 years ago during the Bull Lake glaciation, one of three glacial episodes responsible for carving the park’s dramatic scenery.

About 3 kilometers west of the entrance station, visitors often spot graceful bighorn sheep at the Sheep Lakes viewpoint. In late spring, the sheep descend from higher elevations to the pair of lakes here to graze on grass and eat the salty soil to replenish themselves with minerals not available at higher elevations. Both lakes are kettles — large potholes that form when retreating glaciers strand big blocks of melting ice, which create depressions in the landscape that then fill with water.

The Sheep Lakes are located on the edge of Horseshoe Park, a lush meadow where nibbling elk are often visible and an ideal place from which to spot more glacial features. To the west, Fall River Valley’s U-shaped profile, created by the valley’s very steep walls and flat floor, is characteristic of glacial landscapes. Unlike rivers, which carve V-shaped profiles in valleys, glaciers drag abrasive blocks along both the sides and floor, eroding downward and outward at the same time.

Another type of glacial hallmark visible in Horseshoe Park and elsewhere is moraines, ridges of till that pile up along the toe and sides of a glacier when the climate temporarily stabilizes and the positions of the ice margins remain fixed for a time. When a glacier eventually retreats, the cross-valley ridge marking the ice’s furthest extent is called a terminal moraine, while those along the sides are known as lateral moraines.

Because they’re covered with pine trees, Horseshoe Park’s moraines contrast with the grassy meadows that cover the rest of its floor. The long, narrow moraines that formed during the Pinedale glaciation — the most recent glacial episode, which ended just 10,000 years ago — are especially easy to spot from the bird’s-eye vantage at Rainbow Curve, a viewpoint located about 19 kilometers west of the Fall River entrance station. Because the volume of ice in the valley during the Pinedale episode was less than that during the preceding Bull Lake, the moraines don’t quite fill the valley.

The Alpine Visitor Center's roof is reinforced to withstand the copious snow that makes Trail Ridge Road so challenging to open each spring. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

A few kilometers past Rainbow Curve, Trail Ridge Road climbs above the timberline, which in Colorado averages about 3,500 meters. Coincidentally, this is about the same elevation that the surfaces of the Pleistocene glaciers reached. Above this elevation, the gently rolling upland didn’t collect enough snow to form glacial ice, so its topography has changed little since pre-glacial times.

For the next 18 kilometers, Trail Ridge Road remains above the treeline, so you’re completely immersed in the quintessential Rocky Mountain landscape. If you look closely, you may see hardy wildlife scurrying through this wild and windy place, including camouflaged ptarmigans, squeaky hamster-like picas, and furry, yellow-bellied marmots. You can learn more about this fragile ecosystem, where the annual growing season is sometimes just 40 days long, at the Tundra Communities Trail, an easy 30-minute walk from the Rock Cut viewpoint, where you can also admire some shapely schist and gneiss spires.

In the distance some 20 kilometers to the southeast, the top of 4,346-meter-high Longs Peak, one of the tallest in Colorado, is an especially dramatic sight. Like Switzerland’s famous Matterhorn, Longs is a glacial horn — a high peak that forms where several glaciers diverge from a single point, whittling the broader highland into an isolated mountain. Longs is particularly distinctive due to its flat top, a remnant of the once-rolling uplands that existed here prior to the ice ages. The bowl-shaped depression carved out of the mountain’s steep north side is a cirque, a feature that forms at the very top of a glacier and marks the dividing line below which glaciers excavated significant volumes of rock and above which little erosion occurred. The cirque visible from Trail Ridge is at the head of Glacier Gorge. An even more dramatic cirque near the summit of Longs Peak is visible from Estes Park. At the head of this cirque is an extremely steep, diamond-shaped wall. Known as the Diamond, this headwall is one of the tallest in North America and is a famous granite proving ground for experienced rock climbers.

The Longs Peak Diamond is a world-famous rock-climbing destination. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

About 4 kilometers past Rock Cut, Trail Ridge crosses its highest point at 3,713 meters’ elevation. From here, the asphalt descends a few kilometers to reach the Alpine Visitor Center, which is perched at the lip of the cirque in which the Fall River glacier accumulated. Originally built in 1935, the center has a low architectural profile and a distinctive roof reinforced with large beams to help it withstand the extreme winds and the crushing weight of more than a dozen meters of snow that can cover the building in winter. The center’s back windows offer one of the best views in Colorado, a panorama looking down Fall River Valley toward Longs Peak. To the left of the valley rises Mount Ypsilon, a glacial horn carved from the metamorphic bedrock.

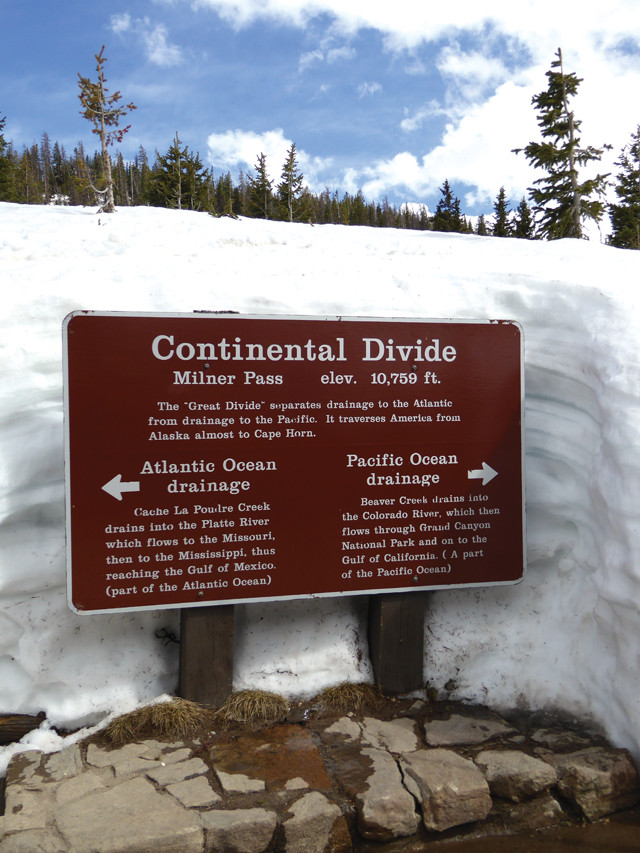

Although it isn't Trail Ridge Road's highest point, Milner Pass is part of the continent's rugged backbone that separates the Atlantic and Pacific drainages. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Visitors commonly spot elk and other wildlife alongside Trail Ridge Road. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Continuing west from the visitor center, Trail Ridge Road does something rather unusual: It drops down to the Continental Divide at Milner Pass, which is located at 3,279 meters. It’s natural to expect that the divide, which demarcates land draining toward the Pacific Ocean from land draining toward the Atlantic, would be situated along the highest ridge in the area. However, the highest ground doesn’t always mark the drainage divide; what counts is the location of the highest continuous ridge, which, here, lies west of the highest topography.

Many visitors whose accommodation is in the more trafficked eastern part of the park turn around at the Continental Divide and retrace their steps. But if you have the time, descend the western slope at least to Farview Curve, 10 kilometers west of the Alpine Visitor Center. There you’ll be treated to yet another stunning view — into the upper Colorado River Valley, which once hosted the largest glacier in the entire park.

Even better, continue all the way down to Grand Lake, the park’s western gateway town, which is much less hectic than Estes Park. You’ll drive alongside the Colorado, which here is a much smaller and more peaceful stream than it is in the Grand Canyon and elsewhere downstream. It’s a favorite destination for anglers, as well as moose. Coyotes, elk, mule deer and beavers can also often be seen in this quieter portion of the park. As you enter Grand Lake, you’ll pass a tall hill of light gray bouldery debris, which is part of a moraine left behind by the Colorado River glacier when it retreated 10,000 years ago. This sight completes the journey along the road the two snow-removal crews work so hard to open — and the spot where the west road crew will start all over again come April, when the late spring sun begins to melt another winter’s snow from the jagged Rocky Mountain landscape.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.