by Mary Caperton Morton Wednesday, September 2, 2015

Hells Canyon, the deepest gorge in North America, is challenging to get to, but it's great to raft or boat. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

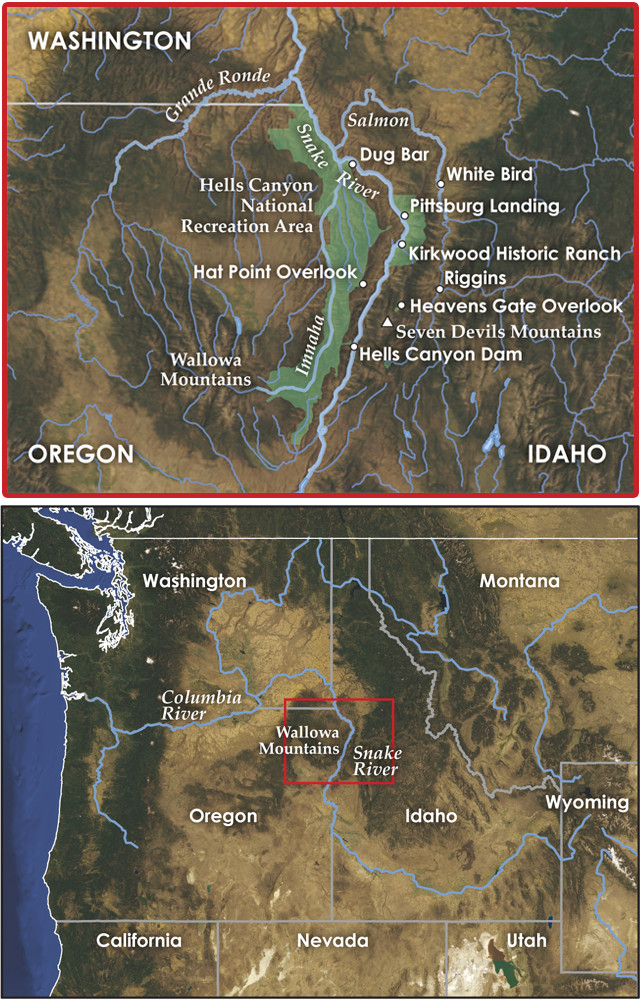

Hells Canyon forms part of the Oregon-Idaho border. Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI.

Why would you ever visit a place called Hells Canyon? Especially given how hard it is to get there: Few roads and only steep, difficult trails run down into the 2,400-meter-deep gorge — the deepest canyon in North America — which forms part of the border between Oregon and Idaho. Despite its remote and rugged challenges, however, Hells Canyon has attracted visitors for thousands of years, from the Clovis people and Native Americans to turn-of-the-century gold miners, sheep ranchers and homesteaders.

Today, the canyon is popular among whitewater rafters and fishing enthusiasts. A trip through Hells Canyon, with its diverse geologic pedigree involving 300 million years of island arcs, volcanism and catastrophic floods, will also delight geology-minded travelers. You don’t even need to be an extreme adventurer to enjoy the canyon: Shove off with a reputable rafting company and you’ll barely even need to paddle.

Hells Canyon has been gouged deep into Earth’s crust by the sinuous Snake River, which drains a massive watershed spread across six states and dozens of mountain ranges, from the Tetons in Wyoming to the Wallowas in Oregon.

Measured from the top of Idaho’s Seven Devils Mountains, on the east rim, to the bottom of the gorge, Hells Canyon drops down 2,436 meters, making it deeper than the Grand Canyon. But for all the canyon’s depth, the Snake River hasn’t been at work carving it for all that long: Geologists think the canyon began forming only about 6 million years ago.

This terrace above the banks of the Snake River was left behind by the catastrophic Bonneville Flood, which roared through Hells Canyon about 15,000 years ago. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

Columnar basalt forms when thick lava cools slowly, fracturing along joints to form mostly hexagonal columns. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

Today, the river flows from Wyoming across southern Idaho before turning north into Hells Canyon, eventually unloading into the Columbia River near Kennewick, Wash. But in its nascent phase millions of years ago, the Snake may have run in the opposite direction: Many of the tributaries of the Snake River flow south. During this early phase, the Salmon River, now a tributary to the Snake, was likely Idaho’s main river. As the region was uplifted by tectonic forces arising from the Cascadia Subduction Zone and the Yellowstone Volcanic Complex, the river’s flow was tipped in the opposite direction and the Snake took over from the Salmon.

Hells Canyon itself may not be very old in terms of geologic time, but the rocks exposed along the length of the 64-kilometer-long canyon are much older, dating back 300 million years to when this part of Idaho was oceanfront property and Earth’s landmasses were joined in the supercontinent Pangea.

The oldest rocks in Hells Canyon are exposed in the narrower stretches of the canyon, where the river has incised deeper and cut further back in time. These dark basalts originally erupted along an arc of volcanoes situated in the proto-Pacific Ocean. Over millions of years, the chain of volcanoes subsided and were colonized by corals that built massive underwater platforms of limestone, now exposed in the northern end of Hells Canyon, near where the Grande Ronde River tributary meets the Snake.

The Sheep Creek Ranch was built in Hells Canyon in 1913. Today, it's managed by the U.S. Forest Service and looked after by a caretaker who welcomes visitors to the homestead. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

During the Permian and again throughout the Mesozoic, massive bodies of molten rock called plutons were thrust upward from Earth’s mantle into the older rock layers, where they slowly cooled and crystallized into granite. These intrusive layers are exposed in Hells Canyon in several locations along both the east and west rims of the canyon.

Between 130 million and 17 million years ago, what is now the Pacific Northwest was added to North America through a series of collisions between the continent and offshore landmasses and islands. The accretion was accompanied by copious volcanic activity, including massive flood basalts from the Columbia volcanic province, which created a high plateau. It was into this plateau that the Snake began carving its path about 6 million years ago.

Most of the carving of Hells Canyon likely took place during the last 2 million years, when melting glaciers and catastrophic floods from large lakes formed by glacial meltwater boosted the river’s erosive power. One of the most dramatic erosive events in Hells Canyon took place about 15,000 years ago, when spillover from prehistoric Lake Bonneville, in what is now northwestern Utah, sent a flood through Hells Canyon 1,000 times greater than present-day maximum river flows.

At the peak of the flood, an estimated 930,000 cubic meters per second of water gushed over the Snake River Plain at speeds faster than 100 kilometers per hour. Geologists think the floodwaters widened Hells Canyon more than deepened it, transforming the margins of the riverbanks more so than the depths of the riverbed. The most dramatic changes still visible today are the large terraces a hundred meters above the original riverbanks that were deposited as the floodwaters slowed in wider sections of the canyon, dropping loads of debris.

Big horn sheep descend to the river to drink. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

These geometric pictographs, painted with red ochre pigments, are thought to be about 2,000 years old. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

Despite Hells Canyon’s navigational and logistical difficulties, people have called the gorge home for at least 13,000 years. Ancient rock shelters, Clovis points and pictographs found within the canyon hint at seasonal occupation by some of the first people in North America, as well as, more recently, by the Nez Perce, Shoshone-Bannock, Northern Paiute and Cayuse tribes, all of whom were drawn to the canyon’s depths by mild winters and productive foraging and fishing.

Hells Canyon was barely glimpsed by the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1806, which followed the Salmon River to its confluence with the Snake in Hells Canyon before turning back to explore another route. In 1811, the Wilson Price Hunt expedition tried to descend the Snake to the Columbia River in wooden canoes, but they too turned back in the vicinity of the present-day Hells Canyon Dam due to hunger and unusually cold conditions.

In the 1860s, gold was discovered along river bars at the northern end of Hells Canyon and soon, placer mining operations began spreading upriver, though none were very successful. Toward the turn of the 20th century, mining efforts switched to hard-rock mining for iron-rich ore, although due to the low grade of the ore and the logistical difficulties presented by the canyon’s steep walls and rugged terrain, many operations went out of business within a few years. Evidence from this time period can be seen at the Rankin Mill site near the Seven Devils Mountains and the Eureka Bar/Mountain Chief mining complex near the mouth of the Imnaha River.

The most visible legacy in Hells Canyon is from the homestead and sheep-ranching era, which began in the late 1800s and continues today. At first, individual families settled onto 65-hectare homesteads, with more than 100 families living along the river by 1910. But the isolation and lack of tillable farmland were disheartening, and by 1918 only a handful of ranches remained in operation.

Numerous houses and outbuildings remain in Hells Canyon, some in better repair than others. Most of the active ranching operations are located along the Imnaha River, a tributary of the Snake, with the Dug Bar and Johnson ranches still standing in Hells Canyon. Several ranches reverted to federal control and a few of these have been preserved as museums, open to the public, including the Kirkwood Ranch, located at the mouth of Kirkwood Creek. Many of these abandoned places, with their overgrown orchards and gardens, have created prime habitat for black bears, elk, mule deer and bighorn sheep. Cougars and coyotes also call the canyon home, although they are rarely seen.

Today, much of Hells Canyon is protected within the 264,000-hectare Hells Canyon National Recreation Area (HCNRA), which includes 87,000 hectares of designated wilderness and the 4,900-hectare Hells Canyon archaeological district. The archaeological district preserves more than 500 prehistoric, mining, homestead and ranching sites, many of which are on the National Register of Historic Places.

Numerous challenging trails run along the Snake River through Hells Canyon, including this scenic path to Suicide Point. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

Small sandy beaches along the river provide camping spots for rafters and jet-boaters alike. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

The best way to see North America’s deepest canyon is from the river’s perspective, and a number of rafting and jet-boating companies offer day and overnight trips into the heart of Hells Canyon. The rapids in Hells Canyon were formed when side streams, rock falls and landslides deposited boulders and large debris in the river channel, creating short stretches of turbulent water separated by wide calm pools of deep water, a type of river topography known as pool and drop.

Most of the Hells Canyon rapids fall into the Class 1, 2 or 3 difficulty levels, with only two — Wild Sheep and Granite rapids — being gnarly enough to warrant a Class 4 rating, defined by American Whitewater as “intense, powerful but predictable rapids that require precise boat handling.” As with all whitewater rivers, classifications can shift as water levels change; some rapids grow more intense at high water, while others become more hazardous at low water, when more rocks are exposed at the water’s surface.

The flow rate of the Snake River is controlled entirely by the demand for hydroelectric power, with rates fluctuating throughout the day from 7,000 to 20,000 cubic feet per second. Flow rates are usually highest in the heat of the day during the summer, when demand for power is highest. The dam-controlled flow rate means the Snake can be boated year-round, though most commercial trips run in the spring and summer months, when warmer air temperatures make for a more pleasant river experience.

Despite the wilderness designation, Hells Canyon is not motor-free. When the HCNRA was established in 1975, a loophole was left open to allow jet boats on the Snake River. These high-speed, shallow draft boats are able to plunge upstream even through the river’s Class 4 rapids, allowing sightseers and fishermen access to the upper reaches of Hells Canyon in a day-long trip.

Most boating companies operate out of Lewiston, White Bird or Riggins, Idaho. Rafting trips begin below the Hells Canyon Dam and run downstream for three to five days, taking out at either Pittsburg Landing or Heller Bar. Jet-boat trips usually begin at Heller Bar and run upstream as far as the Hells Canyon Dam before returning downriver, a round trip of 380 kilometers. Both rafting and jet-boat trips can be customized for fishermen, families, history and hiking buffs.

A river guide scouts Granite Rapids, one of two Class 4 rapids in Hells Canyon. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

You don’t have to be a river rat to visit Hells Canyon, but getting into and through the place on foot can be daunting. There is only limited access by car: An unpaved forest road descends to the river at Pittsburg Landing and a narrow, winding road dead ends at the Hells Canyon Dam. Overlooks at the Heavens Gate Lookout, near Riggins, Idaho, and the Hat Point Overlook near Imnaha, Ore., offer views down into the canyon from the east and west rims, respectively.

A number of hiking and horse trails run down into and through Hells Canyon, with the Snake River Trail offering access from Pittsburg Landing into the Hells Canyon wilderness. However, steep trails, rock slides, rattlesnakes, poison ivy, hot summers and frigid winters can make hiking in the canyon a hellish experience indeed. Better stick to the river, sit back in a raft and enjoy the ride!

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.