by Sam Lemonick Thursday, June 7, 2018

What’s the quickest way to see the Scottish Highlands and Africa? Take a trip to Nova Scotia. The southeastern Canadian province is a mash-up of continental fragments whose landscape testifies to the power of glacial and tidal forces. Slightly smaller than West Virginia, the province is easy to get around and is packed with geological sites without being overwhelming.

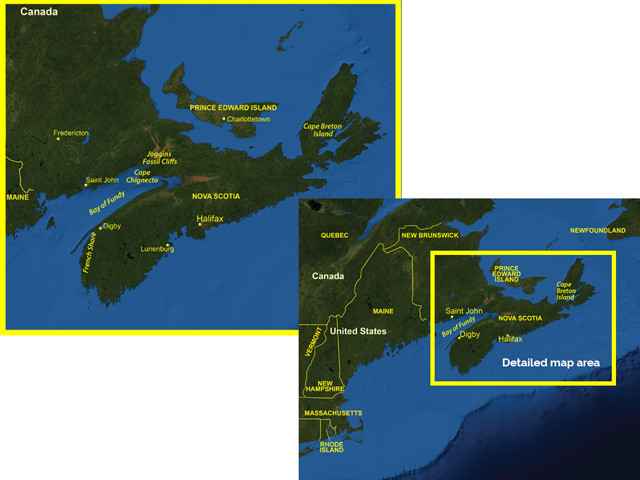

Credit: AGI/NASA

The geological diversity is the result of tectonic processes that began when the supercontinent Pangaea started to break up in the Early Jurassic period, about 200 million years ago. After the split, the North American Plate took with it pieces of continental crust that had previously been associated with what we now consider Africa and Europe. In western Nova Scotia, Cape Chignecto’s striking Three Sisters, pillars of red sandstone climbing out of the sea, are the eroded remnants of a piece of the supercontinent Gondwana that later became northwestern Africa. The province’s Cape Breton Island was once part of the same landmass as Scotland and parts of Ireland.

Historic Lunenburg is a UNESCO World Heritage Site known for its quaint architecture and historic sailing ships. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/King Ho Yim

Nova Scotia is connected to the neighboring province of New Brunswick by a narrow isthmus. Its westernmost point is less than 75 kilometers from Maine, but the long, narrow Bay of Fundy, home to some of the largest tides in the world, makes a trip by car considerably longer. At 170 kilometers at its widest and 575 kilometers long, the province can be divided into three main areas: the mountainous Cape Breton Island to the northeast; the central low-lying plains and southern and eastern coasts reminiscent of northern New England; and the thickly forested Cape Chignecto, closest to the mainland.

The easiest way to navigate Nova Scotia is by car. Its system of Travelways — road routes that circumnavigate the province — passes by most of the major destinations. The Evangeline and Lighthouse trails take you around Nova Scotia’s southwestern edge along the French Shore (where the signs aren’t in English). The South Mountain Batholith — formed about 370 million years ago when magma pushed up into existing strata and slowly cooled to form granite — covers 10,000 square kilometers of southwestern Nova Scotia, where glacial forces have had the greatest effect on the topography.

The ocean eroded the sedimentary rocks of the Joggins Fossil Cliffs, exposing strata dating back 300 million years. Credit: ©Dustin M. Ramsey, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 Generic

Glacial drumlins — low, elongated hills created by erosion and sediment deposition beneath a moving glacier — dominate southern Nova Scotia, most of them pointed toward the sea. In some places, striations in the exposed granite bedrock mark the direction of glacial flow along with the drumlins. Nova Scotia’s southeastern coastline — a series of thin, rocky peninsulas separated by narrow inlets — was also cut by glaciers, recording where rock and earth were carved out as recently as 12,000 years ago, when the last major glaciers retreated.

If you drive northeast from the French Shore, you’ll pass through the historic port town of Lunenburg, a UNESCO World Heritage Site known for its quaint architecture and historic sailing ships. Further inland, about 60 kilometers north of Halifax, the province’s coastal capital, is the National Gypsum Quarry, the largest gypsum quarry in the world.

Gypsum isn’t the only thing that’s been recovered from the quarry: Two nearly complete mastodon skeletons were unearthed there in the early 1990s. The unlucky mastodons fell into a mud sinkhole in the gypsum bedrock about 90,000 years ago and were subsequently covered by 30 meters of sediment. The bones, many of which are poorly preserved, are held by the Museum of Nova Scotia, but plenty of tourist traps in the area feature replicas.

Low tide along the Bay of Fundy. The bay is home to the largest tidal range in the world. The average difference between high tide and low tide is 16 meters. Credit: ©Shutterstock.com/matthewsinger

Visitors can do their own fossil exploring at the Joggins Fossil Cliffs on the Bay of Fundy, 175 kilometers northeast of the quarry. The bay’s powerful tides have eroded the sedimentary rock of the Joggins Cliffs, exposing strata dating back to the Pennsylvanian period, more than 300 million years ago. Stairs from the Joggins Fossil Centre at the top of the cliffs lead down to the base, which is only open for a few hours at a time as the tides allow. On the way down, helpful markers post the age of the rocks as you descend deeper into the past. At the bottom, volunteers show you which patterns in the rocks are footprints and which are products of your overactive imagination. In just a few minutes, you can find reptile tracks, tree trunks and ripples left by water currents. When Charles Lyell visited the cliffs in the 1840s and 1850s, he discovered fossils of Dendrerpeton acadianum — one of the earliest-known species of four-legged terrestrial vertebrates, or tetrapods — that lived more than 300 million years ago.

The Fossil Cliffs wouldn’t exist without the Bay of Fundy. The average difference between high and low tide is about 16 meters, the height of a five-story building. Every 12.4 hours — the length of the tidal cycle — more than 30 trillion gallons of water flow in and out of the bay. The extreme tides are a product of the long, narrow shape of the bay and good timing. Water naturally sloshes back and forth, or oscillates, from one end of the bay to the other, like water in a bathtub. Due to the geometry of the bay, it takes about 12 hours to complete a period of oscillation. That’s the same time interval between high and low tides. This results in tidal resonance. Because the tide and the sloshing are in sync, their effects amplify each other.

The scenery on Cape Breton Island is reminiscent of the Scottish Highlands. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Pgiam

The effect of the rushing tide is especially pronounced at a few narrow spots in the bay, some of which offer the opportunity to raft the muddy water of the tidal bore, as the currents generated by the tides are called, in motorized rubber rafts. The powerful currents are also put to use for hydroelectric generation. Since 1984, the 20-megawatt Annapolis Royal Generating Station has been the only tidal power station in North America, generating enough electricity to power about 4,000 homes.

Across the Bay of Fundy from Joggins is Cape Chignecto, where the highlands end in 200-meter cliffs dropping into the sea. The westernmost tip of Chignecto was part of Gondwana, which later separated into South America and Africa. The red sandstone protruding from the beach certainly looks foreign after driving through Nova Scotia’s largely uninhabited northern peninsula to reach the Cape Chignecto Provincial Park, home to 50 kilometers of hiking trails. The hilly, forested terrain of the Avalon Uplands, which stretch roughly east-west from Cape Chignecto to Cape Breton Island, is a much-eroded extension of the Appalachian Mountains, built up about 450 million years ago during the formation of Pangaea.

At the other end of the Avalon Uplands, Cape Breton Island may be the most breathtaking part of Nova Scotia. The Cabot Trail road winds up enormous bluffs that drop off precipitously into the Atlantic Ocean. Like Cape Chignecto, this part of Nova Scotia is not part of the North American Plate; it’s a fragment of a small microcontinent, or “terrane,” called Avalonia that sat between the North American and Eurasian plates before Pangaea broke up and was then split by the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The Aspy Fault, a 40-kilometer-long trench that runs north-south through the highlands, is evidence of that split. The fault was once the western end of the Glen Fault, which now crosses Scotland and part of Ireland. From a turnout on the Cabot Trail, the Aspy Fault looks as straight as if it was plotted with a ruler. Even without the fault it seems obvious that this area was once connected to Scotland, with its tall grassy bluffs and rocky hills. A kilted bagpiper striding across the highlands wouldn’t seem out of place, although visitors are more likely to encounter black bears.

Seeing Nova Scotia’s varied landscape can be easily accomplished in a week or even a few days if you’re ambitious. It’s hard to imagine an easier or faster way to see geologic highlights from North America, Northwest Africa and the British Isles all in one trip.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.