by Terri Cook and Lon Abbott Monday, April 9, 2018

Wadi Nakl, the Grand Canyon of Arabia, is just one of Northern Oman's many highlights. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

Hot, off-the-beaten path and situated amid an oftentimes turbulent region, Oman may not top many travelers’ lists of desired destinations. But if you’re into geology, it should: The small sultanate, itself politically stable, hosts the world’s biggest and most intact ophiolite, along with stunning canyons that plunge into turquoise swimming holes, lush palm oases and Bronze Age tombs, pristine beaches where endangered sea turtles struggle back to the sea after laying their eggs, and endless fields of sand dunes where you can camp beneath the stars. You’ll come for the ophiolites, and stay for the rest.

The ramparts of Muscat's fort, built by the Portuguese in the 1580s, rest atop a sliver of Earth's mantle. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

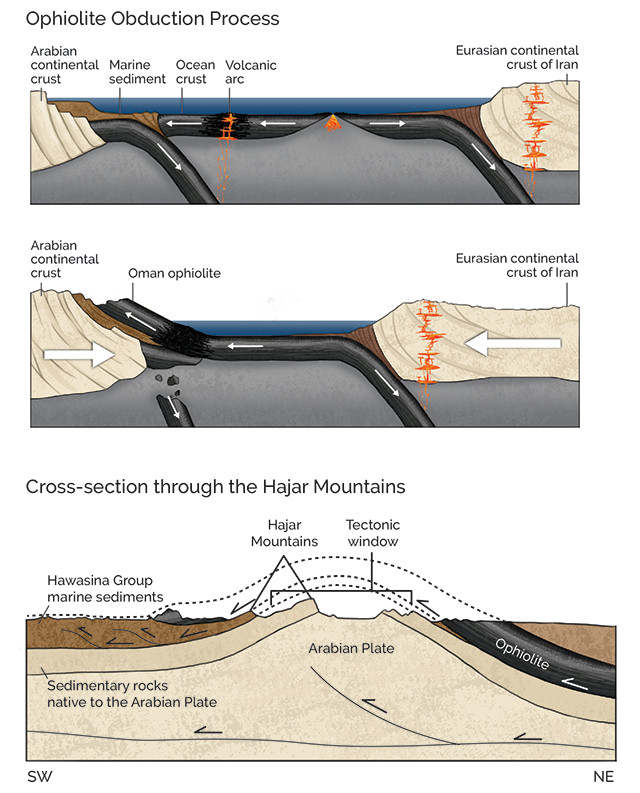

“Ophiolites, slivers of oceanic crust and upper mantle that have been shoved onto a continent, hold special significance for geologists because of their rarity and the powerful testimony they offer about our planet’s dynamism. The vast majority of ocean crust is recycled back into the mantle, and the occasional bits that are thrust up onto the edges of continents are typically dismembered and scattered across the landscape because the tectonic forces acting on them are incredibly powerful.

But this is not the case in Oman, where the ophiolite layers reveal the complete stack of rock types that compose oceanic crust. Our family traveled to Oman last December to see these unusual rocks, which form the dark hills behind the capital city of Muscat’s whitewashed buildings, medieval fortifications and vibrant waterfront. We spent seven memorable days exploring a compact driving loop through the spectacular Hajar Mountains from Muscat, enjoying the country’s many scenic and cultural highlights while never venturing far from the unique rocks that drew us there.

Visitors to northern Oman will need a car — preferably a four-wheel-drive vehicle — to get around. Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI.

’’' Like most visitors to northern Oman, we began our tour in Muscat, a modern city with a long history as a commercial trading hub. Omanis have been master seafarers and traders for thousands of years, sailing their dhows — traditional wooden cargo ships — to trade with empires that have risen and fallen in China, Egypt, Europe, India, Mesopotamia and Persia. A visit to Mutrah, Muscat’s lovely port area, is an ideal way to get acquainted with modern Omani commerce, the city’s connection to the sea and the sultanate’s famed ophiolite.

'

Mutrah, the waterfront of Muscat, Oman's capital, is a great place to stroll between hills of ophiolite and the sparkling Arabian Sea. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

The Oman ophiolite likely formed when oceanic crust was thrust atop the Arabian continental crust as that buoyant material encountered the subduction zone and halted subduction. Today, the ophiolite has eroded and the deep rocks beneath it are exposed through a tectonic window in the Hajar Mountains. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

Lush terraces near the town of Bilad Sayt are irrigated by traditional canals originally constructed more than 1,500 years ago. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

“The ophiolite consists of a sequence of mafic and ultramafic (dark, iron- and magnesium-rich) igneous rocks. At the bottom of the ophiolite lie the mantle rocks, which make up most of the hills above Muscat and consist of peridotite — a dense, coarse-grained rock composed of the minerals olivine and pyroxene. Above the peridotite lies oceanic crust, consisting of a sequence of rocks that crystallized from the magma that rose from the partially melted mantle below.

One inspiration for visiting Oman was to see the “Grand Canyon of Arabia.” Locally called Wadi Nakl — wadi is the Arabic word for a valley — this stunning canyon is carved into the south side of the Hajar Mountains, which rise to 3,000 meters elevation a mere 60 kilometers from the coast. We had two options to get there from Muscat: a relaxing two-hour drive on an impeccable motorway or a rugged four-wheel-drive adventure through Wadi Bani Auf, which crosses Jebel Akhdar, Oman’s highest massif. Our teens chose the latter — and we all received a great introduction to Oman’s world-class geology en route.

The 12th-century Bahla Fort towers above an oasis of the same name. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

“Along the 100-kilometer drive from Muscat to the foothills town of Nakhl, we passed through a stack of Late Cretaceous through Paleogene marine limestones. The presence of these rocks reveals that soon after ophiolite obduction ended, about 73 million years ago, the region sank below sea level, where the carbonate sediments that would form these limestones slowly accumulated until a second uplift event beginning about 40 million years ago raised the modern mountains.

The four-wheel-drive trip through Wadi Bani Auf features 15 percent grades, steep drop-offs and spectacular views into several slot canyons, including the twisting Snake Gorge. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

' “The road returns to the ophiolite as it reaches the foothills on the way to Al Awabi, an Omani town that is surrounded by lush palm plantations. Here, where the road turns south into the heart of the rugged mountains, the rocks changed from ophiolite to Mesozoic limestone as we crossed a thrust fault at the base of the ophiolite. These limestones, which make up the Hajar’s core, are native to the Arabian Plate, having accumulated atop its basement rocks during a long interval of tectonic quiescence in the region that reigned from about 280 million to 95 million years ago.

That quiet was shattered, however, when the ophiolite was obducted. For years geologists have debated how such dense material ended up atop more buoyant continental crust. Currently, the leading hypothesis is that oceanic lithosphere attached to the Arabian Plate began to subduct beneath what would later become Oman’s ophiolite, in the process drawing the buoyant Arabian continent down and closer. When Arabian continental crust reached the subduction zone, it was too light to be subducted, so a head-on collision ensued, during which the ophiolite was plastered onto the edge of Arabia.

The scenery along the 6-kilometer Balcony Walk in Wadi Nakl is reminiscent of the American Southwest. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

’' “Having crossed the thrust fault underlying the ophiolite, we entered what geologists call a tectonic window: a view into the stratigraphy of the rocks below. Uplift of the Hajar Mountains 40 million years ago created a giant anticline that bent the ophiolite upward. Subsequent erosion stripped the ophiolite off the top of the arch, exposing a “window” into the rocks below. Not far south of Al Awabi, the pavement ends and the road crosses into older, metamorphosed sedimentary rocks that underlie the limestones. These rocks were deposited between about 750 million years ago — during one of the “Snowball Earth” events when Earth’s surface nearly froze over completely — and about 330 million years ago, when they were metamorphosed during the assembly of the supercontinent Pangea. ’' The scenery in Wadi Bani Auf is desolate but magnificent, and it becomes even more dramatic farther south, where the road crosses back into the limestones, and where the Hajar grow taller and so much more rugged that you need a four-wheel-drive to safely navigate the 15 percent road grades, vertical drop-offs and narrow shelves precariously perched beneath the soaring cliffs. Along the way, you can visit the chasm of Snake Gorge, Arabia’s premier canyoneering route, as well as Little Snake Gorge, and our favorite: a hike up a short slot canyon to the village of Bilad Sayt, which is surrounded by a green carpet of terraced fields irrigated by a system of aflaj (canals) constructed more than 1,500 years ago. Oman’s aflaj are of such cultural significance that they have been designated a UNESCO World Heritage site.

After reaching the end of our four-wheel-drive geoadventure, we drove the very steep road up to a luxurious “glamping” resort high on the flanks of Jebel Shams, Oman’s highest peak, where we enjoyed a spectacular sunset and spent the night at about 2,000 meters elevation. The next day it was only a few minutes’ drive to Al Khateem, the starting point of the famous Balcony Walk, a 6-kilometer round-trip hike into spectacular 1,000-meter-deep Wadi Nakl canyon. The scenery is reminiscent of the American Southwest, with sheer walls of resistant limestone alternating with benches carved from less-resistant shale. The hike ends at the ghost village of As Sab, which, although it was only abandoned in the 1970s, resembles an ancient Puebloan ruin.

Bahla Fort is built atop an impressive sheeted dike complex. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

''

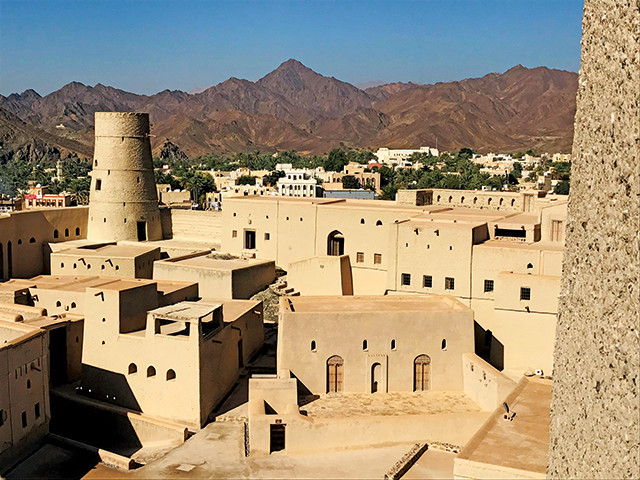

After descending the south side of the Hajar, we arrived in the tourist hub of Nizwa, where there are enough attractions to keep visitors occupied for days. We visited Al Hoota Cave, which has respectable stalactites and stalagmites, as well as a nice geology museum. The scenic drive up onto the Saiq Plateau passes several spectacular terraced villages famed for their orchards and rosewater, a perfume made by steaming rose petals, which Arabs traditionally sprinkle on the hands of guests after dinner. And we visited two impressive medieval forts: Jabrin Castle, built in 1675 by a prominent Omani imam, and the 12th-century <a href=“http://whc.unesco.org/en'list/433'>Bahla Fort, one of Oman’s top sights. Although there are only a handful of interpretive signs, mostly concentrated around Bahla Fort’s mosque, this World Heritage site is very impressive, and we all really enjoyed wandering through its maze of rooms. Our kids eagerly clambered up the many staircases and ladders, coaxing us to follow them with descriptions of the far-reaching rampart views. Meanwhile, we admired the excellent sheeted dike complex — a distinctive segment of the ophiolite — on which the fort was built.

It took us a while to find another highlight of the Nizwa area, a line of 20 “beehive tombs” constructed between 3,000 and 2,000 B.C. on a lonely ridgeline above the village of Al-Ayn. Despite being a World Heritage site, there are no signs marking the tombs’ location. After searching for an hour, we finally caught a glimpse of one of the tombs silhouetted on the skyline. Our frustration gave way to elation with the realization that we were alone at this striking site. The area’s Bronze Age inhabitants constructed the tombs by piling up desert-varnished sandstone blocks to make 5-to-7-meter-high beehive-shaped rooms in which they interred their dead. The sandstone belongs to the Hawasina Group, a pile of deep marine sedimentary rocks that were folded like an accordion as they were thrust onto the Arabian continental margin along with the ophiolite.

The grandeur of this site is enhanced by the nearby countenance of Jebel Misht, a nearly vertical 1,000-meter-high wall of Triassic limestone that looms above the tombs. Because this limestone overlies Late Triassic basalt, geologists have concluded that it represents what was once an isolated seamount, which was decapitated and shoved atop the continental margin by the overriding ophiolite during obduction. Burial by the ophiolite, which was later eroded away at this site, caused the limestone to recrystallize, making it especially resistant to erosion and explaining why it remains so sheer and tall today. Thanks to this remarkable geologic history, it’s Arabia’s premier big wall rock-climbing venue.

The sheer wall of Jebel Misht dwarfs a Bronze Age beehive tomb near the village of Al-Ayn. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

Like Jebel Akhdar, the southeastern Hajar Mountains are another large arch uplifted about 40 million years ago during an episode of compression that was likely triggered by subduction of the Arabian Plate beneath Iran along the Makran Subduction Zone. The foothills south of these mountains preserve an especially wide swath of oceanic lithosphere, including excellent examples of the layered gabbros that form the base of oceanic crust. But southeast of the town of Al Mintirib, the seemingly endless expanse of dark ophiolite finally ends at a large field of southwest-trending longitudinal dunes called the Sharqiya Sands.

’'

The moderate hike up Wadi Shab parallels a historic irrigation canal still used to water date palms and other crops. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

“Don’t miss spending a night at one of the many desert camps scattered throughout the dune field; our day and night in this sea of sand, partaking in warm Bedouin hospitality, gazing up at inky black skies full of twinkling stars, and enjoying a majestic sunrise and sunset on the dunes, was the highlight of the trip for our kids. They especially reveled in the four-wheel-drive “dune bashing” tour, during which our expert desert driver coaxed the Land Cruiser up 35-degree dune faces farther than we thought possible. Although the plunges down the same steep faces agitated the butterflies in our stomachs, our kids giggled the entire time; their only regret was that we didn’t have another day amid the dunes so that they could learn to sand-board.

Local Bedouin enjoying a break amid the spectacular Sharqiya dunes. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

Refre'hing swimming holes await hikers in the canyon of Wadi Shab. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

'

The sun's first rays illuminate fresh tracks made by an endangered green sea turtle crawling back to the sea. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

Another must-see site in northern Oman is Ras al-Jinz, the easternmost point on the Arabian Peninsula and the location of one of the world’s most important nesting sites for endangered green sea turtles. Despite the loud grumbling from our reluctant kids when we rousted them at 4 a.m. for the guided tour of the nesting beach, they admitted the experience was well worth the effort once they witnessed a mother turtle laboriously crawl back into the sea after laying her clutch of eggs. Because the turtles always vacate the beach before sunrise, visitors are free to wander there on their own during the day, and we had a wonderful time strolling along the cliff-backed beach, photographing fresh turtle tracks in the low morning light.

“After relaxing for a day on the coast, we set out to explore more of the eastern Hajar Mountains, which are festooned with ancient aflaj. We took a leisurely stroll up Wadi Bani Khalid to swim at a deep swimming hole next to a bustling snack bar. Then we ventured up Wadi Shab, near the coastal town of Tiwi, a longer but still gentle walk along one of the World Heritage canals that parallels a perennial creek with cascading waterfalls and several turquoise-blue swimming holes, all set deep beneath soaring limestone walls every bit as spectacular as the canyons of the American Southwest.

Wadi Shab, which lies just 100 kilometers southeast of Muscat on a modern motorway, is an easy half-day trip from the capital. All of the sites we visited could be reached in a day from Muscat, illustrating how much geologic diversity — and how many cultural attractions — you can enjoy on even a short visit. Given the steady stream of alarming news emanating from the Middle East these days, it’s understandable that many North Americans are reluctant to venture there. But Oman is an oasis of stability, and few places can rival the geologic and scenic splendor northern Oman packs into such a compact area.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.