by Sam Lemonick Sunday, January 4, 2015

Much of Bermuda's coastline is rocky but the south shore hosts beautiful pink and white sand beaches. Credit: Kelly Speare.

The Bermuda Triangle is not an actual scientific phenomenon. But if a family were looking for a place to disappear to for a week or so, Bermuda is a great choice. Picturesque beaches, beautiful weather and a pleasant mix of Caribbean and British cultures make it a popular vacation destination. It’s also a place where geology and history are on display, making both relaxation and exploration easy.

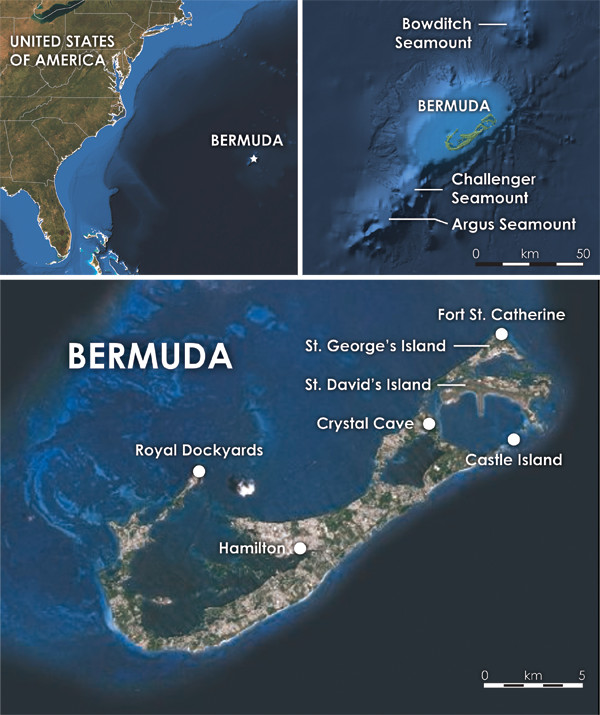

Bermuda comprises a compact group of islands on the southeastern edge of a large reef in the Atlantic Ocean, about 1,000 kilometers east of Cape Hatteras, N.C. The islands of Bermuda sit on one of four seamounts — Bermuda, Challenger, Bowditch and Argus — in a 100-kilometer-long chain. Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI.

Bermuda, a former British colony, inhabits a compact group of islands on the southeastern edge of a large reef in the Atlantic Ocean, about 1,030 kilometers east of Cape Hatteras, N.C. Bermuda itself is a group of islands sitting on one of four seamounts — Bermuda, Challenger, Bowditch and Argus — in a 100-kilometer-long chain running southwest to northeast. The seamounts rest atop the crest of a similarly trending swell, called the Bermuda Rise, that measures 1,500 kilometers long and 500 to 1,000 kilometers wide. The origins of the seamounts and the rise are one focus of the ongoing geological debate over the existence of mantle plumes.

The mid-plate seamounts formed between 45 million and 35 million years ago. Superficially, they resemble the Hawaiian chain and have previously been attributed to hot spot volcanism, but other geologists think they formed during a period of heightened volcanic activity worldwide, while tectonic plates were jostling against each other as the ancient supercontinent Gondwana was finishing its breakup.

An earlier theory suggested that Bermuda and the other seamounts formed as part of a massive eruption along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. But geologists have invalidated this idea based on boreholes drilled into the seafloor that show that the seamounts themselves are much younger than the crust beneath them, which formed at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge about 100 million years ago.

The Bermuda volcano may once have stood as high as 1,000 meters above sea level, but it has long since eroded down to a large plateau; only 7 percent of the plateau is above the ocean surface today. Around the edges of the volcano, coral reefs have formed. Over millions of years, the shells and bones of other sea creatures and ancient reefs settled on the seafloor and were compacted into limestone. The plateau extends northwest from the island about 10 kilometers in a large reef, but off the island’s southeastern coast there are only a few kilometers of shallow water before the shelf drops precipitously. During glacial cycles, sea levels rose and fell, variously exposing and covering Bermuda’s igneous and sedimentary rocks. Today, the above-water island rocks are almost exclusively limestone, sculpted by wind and waves. Around them, cold-water reefs still grow, forming some of the northernmost reefs in the world.

Bermuda is home to a vast system of caves, including Crystal Cave, which boasts impressive stalactites and stalagmites. Caves on the islands are both above and below water. Credit: left: ©Shutterstock. com/Russ Hamilton.

Because limestone is a fairly soft rock and susceptible tormuda is home to a vast system of caves, both above and below water. Scientists think these caves mostly formed when sea levels were lower. Rain — the only source of freshwater on Bermuda — has also carved sinkholes and more than 150 caves across the island.

Crystal Cave abuts Blue Hole Park, which has its own caves for those looking for a less-commercial experience. They don’t rival Crystal Cave, but water shoes, a bathing suit and a flashlight are all you need to check them out. Two interconnected caves, separated by a thin curtain of limestone columns, are accessible. Each cave is a few hundred square meters and flooded with less than a meter of water. The bottom is mostly sandy, but there are some treacherous rocky spots. Hundreds of stalactites hang from the caves’ roofs, which are high enough in most places to walk under, but low enough that you should keep an eye out for them. With a keen eye, you might even be lucky enough to spot a cave lobster.

Geologists suspect sea caves are also hidden in the depths around the island and reef. The evidence for the existence of undiscovered caves comes from crustaceans and other cave dwellers, some of the island’s only native animals. Geologic records show that all known Bermudian caves were above sea level during the last glacial maximum about 18,000 years ago. But some of these species are thought to have existed locally for millions of years, suggesting these animals retreated to deeper caves until sea levels rose again. These former habitats may still exist.

Small, whitewashed houses with peculiar roofs shaped like angular beehives are designed to channel rainwater into cisterns, from which Bermudians get almost all of their freshwater. Credit: left: ©Shutterstock.com/Peter Rooney; above: Kelly Speare.

Aboveground, Bermuda’s landscape features low, rolling hills dotted with small trees. The shoreline is mostly rocky with tide pools, although gorgeous white sand beaches occasionally break up the rugged terrain, especially on the southern coasts. Small, whitewashed houses with peculiar roofs shaped like angular beehives or Aztec pyramids are the norm. The roofs are designed to channel rainwater into cisterns, from which Bermudians get almost all of their freshwater (the remaining water comes from wells that tap the island’s few freshwater lenses). Because of the water resource constraints, Bermudians have long since adapted, even teaching their children about conservation with a simple rhyme: “In the land of sun and fun, we never flush for number one.” (In other words, do not flush the toilet when you urinate.)

Nearly as ubiquitous as the distinctive roofs — and Bermuda shorts — are the forts that line the island’s shores. It was only in the early 20th century that Bermuda transformed into the popular tourist destination it is now. The island became a British naval outpost during the American Revolution, and the British government continued to fortify it throughout the 19th century. Narrow navigable passages through Bermuda’s reefs made it almost impossible for enemies to reach the island quickly; the difficult navigation also made enemy ships easy targets for cannon fire from the shore.

Because of Bermuda’s lack of timber and its strategic importance, it was one of the first places in the Western Hemisphere to have stone forts. Castle Island is the oldest standing British fort on Bermuda, and at just over 400 years old, is the oldest stone fort in the hemisphere. It and the other forts around St. George — the original settlement on Bermuda, dating to 1612 — make up the Historic Town of St. George and Related Fortifications World Heritage Site. Castle Island is now a conservation refuge for the endangered Bermuda skink and the Cahow bird, so it isn’t open to the public. Other parts of the World Heritage Site are open, however, and other forts on the island, like Fort St. Catherine on Bermuda’s northeastern tip, can be toured after paying an entrance fee. Many other forts are free, and visitors can wander through them looking at explanatory placards and nonfunctioning cannons.

Bermuda's landscape features low, rolling hills dotted with small trees. Credit: Christopher M. Keane.

Bermuda’s isolation and long military history have also resulted in a unique record of military and artillery development. Whereas obsolete cannons and artillery pieces in other parts of the world were usually melted down and the metal recycled, Bermudians lacked the means to do so, and shipping the huge guns back to England was impractical. Instead, many were kept or simply dumped over a fort’s walls into the sea below. Some have been recovered and restored and are now on display at forts around Bermuda.

Bermuda's landscape features low, rolling hills dotted with small trees. Credit: Christopher M. Keane.

Much of the largest fort complex, the Royal Naval Dockyard, still stands and now houses the National Museum, which offers a variety of exhibits detailing Bermuda's history, of which the buildings themselves, which once housed soldiers, gunpowder, prisoners and more, are a part. Credit: Christopher M. Keane.

Much of the largest fort complex, the Royal Naval Dockyard, still stands and now houses the National Museum, which offers a variety of exhibits detailing Bermuda’s history, of which the buildings themselves, which once housed soldiers, gunpowder, prisoners and more, are part.

Of particular interest in the National Museum is an exhibit about shipwrecks. Bermuda’s British colony was founded by survivors of one fateful wreck, the Sea Venture, which was part of a group of ships sailing to the Jamestown colony in Virginia. And countless other wrecks have occurred on Bermuda’s reefs, which lie precariously in the middle of otherwise open ocean, along well-trafficked shipping routes, near the path of the powerful Gulf Stream.

Visitors to the museums can view artifacts from shipwrecks, including gold coins, jewelry, weapons and navigation tools. They can also learn about how researchers (and looters) have explored the reefs over the years, using free diving, diving bells — a chamber open on the bottom that can be lowered to the seafloor with free divers inside — and scuba and other modern equipment.

Hundreds of ships have wrecked just offshore of Bermuda; many are still viewable from shore. Credit: Kelly Speare.

Some of the 300 or so estimated wrecks around Bermuda can be visited in person too. Older wrecks are best seen on the western end of Bermuda, whereas more modern ships, including an ocean liner, racing yachts, freighters and warships, can be found to the east.

The paddle-wheel steamer Montana sits in just a few meters of water, where it wrecked trying to refuel in Bermuda on the way to run a Union Army blockade during the Civil War. With a snorkel and fins it’s easy to see the intact bow and stern, including the paddle wheel. Other wrecks, like the enormous Cristóbal Colón or the 19th-century iron-hulled sailing ship North Carolina, require scuba equipment. Exploring any of the wrecks, whether by snorkel or scuba, requires booking an excursion through one of Bermuda’s many dive shops.

Bermuda’s proximity to the United States, its familiar culture and its leisure attractions have long made it a popular choice for stateside travelers. The beaches are concentrated along the southern coast and are a mix of public and private. Some feature Bermuda’s famous pink sand, a result of single-celled, red-shelled foraminifera that live on the reefs. It also has the highest concentration of golf courses in the world, with nine located across the islands’ 53 square kilometers. These courses, six of which are private but still accessible to visitors, attract some of the world’s best golfers. Visitors can also explore the island by bike or on horseback. But off the links and away from the beaches, the country offers a diversity of fascinating and accessible geological and archaeological attractions sure to thrill any curious geotourist.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.