by Kat Cantner and Colin McFadden Friday, January 11, 2019

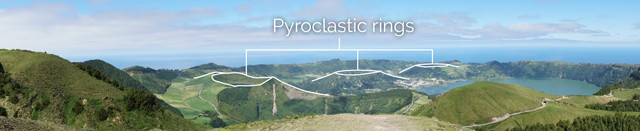

One of the most beautiful places in the Azores, the caldera of Sete Cidades is ringed by hiking trails and trachytic pumice. Credit: Kat Cantner and Colin McFadden.

In the middle of the Atlantic, 1,600 kilometers off the coast of Portugal, lie the Azores, an archipelago comprising nine remote islands, each with its own history, culture and geology worth exploring. Visitors to São Miguel, the largest island, can bathe in a hot spot in the ocean thanks to an unusual geothermal outflow. On Faial, they can view remnants of the most recent eruption that devastated the island. Meanwhile, Santa Maria offers opportunities to see the only fossils in these volcanic islands.

While the isolated Azores, a volcanic island chain spanning more than 600 kilometers, may be diminutive and difficult to find on the map, the islands offer oversize opportunities for sightseeing and adventure that are sure to appeal to almost any traveler, particularly those with an eye for natural and geologic scenery.

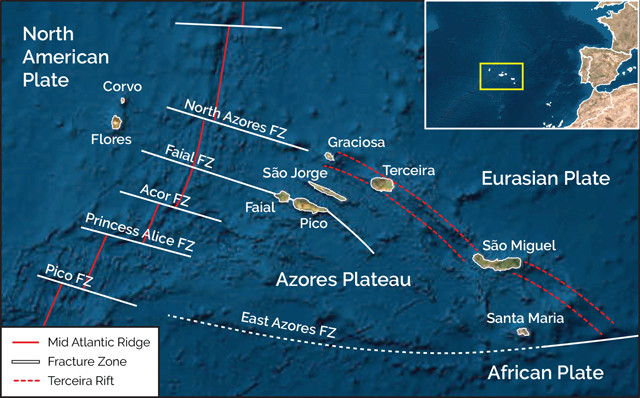

The Azores formed from volcanism associated with both tectonic extension and an underlying mantle plume. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

The Azores may resemble the Hawaiian Islands at first glance, but the geology tells a different story. As in Hawaii, it is thought that a mantle plume contributed to the islands’ formation, but unlike the Hawaiian Islands, the Azores do not exhibit any clear linear chronology. In addition, whereas Hawaii is an intraplate island chain, the Azores Plateau exists at a triple junction where three tectonic plates — the North American, Eurasian and African plates — meet. The eastern edge of the North American Plate is clearly bounded by the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, while the boundary between the Eurasian and African plates is transitional. Rather than being defined by a single fault, the plate boundary is an extensive series of faults and fracture zones. This thickened, fault-laden crust between the two plates forms the Azores Plateau.

The location of the triple junction has moved from south to north since the formation of the Azores Plateau 36 million years ago. Rotation of the plates paired with this migration has resulted in a complicated terrain of faults and rifts that are activated and deactivated as local tectonic stresses shift. The triple junction itself is unique from other such junctions in that it does not involve a subduction zone. Moreover, how much of the volcanic activity that formed the plateau was contributed by the deep mantle plume versus extension associated with the tectonics of the triple junction is still debated.

The local black basalt makes a stunning contrast to the white plaster walls of Ponta Delgada's buildings. Basalt is used alongside white limestone in the elaborate designs of the Portuguese pavement, a ubiquitous feature throughout Portugal and its former colonies. Credit: both: Kat Cantner and Colin McFadden.

São Miguel is home to most of the Azorean population of about 250,000 people, half of whom live in Ponta Delgada, the island’s capital city. With its quintessential Portuguese mosaic sidewalks and striking white plaster and black basalt architecture, Ponta Delgada is a picturesque seaside city. Even though São Miguel is the largest Azorean island at 744 square kilometers, it is still small enough that every part of the island is easily accessible on day trips from Ponta Delgada.

The largest island of the Azores, São Miguel, formed by the fusion of two volcanic islands 50,000 years ago. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

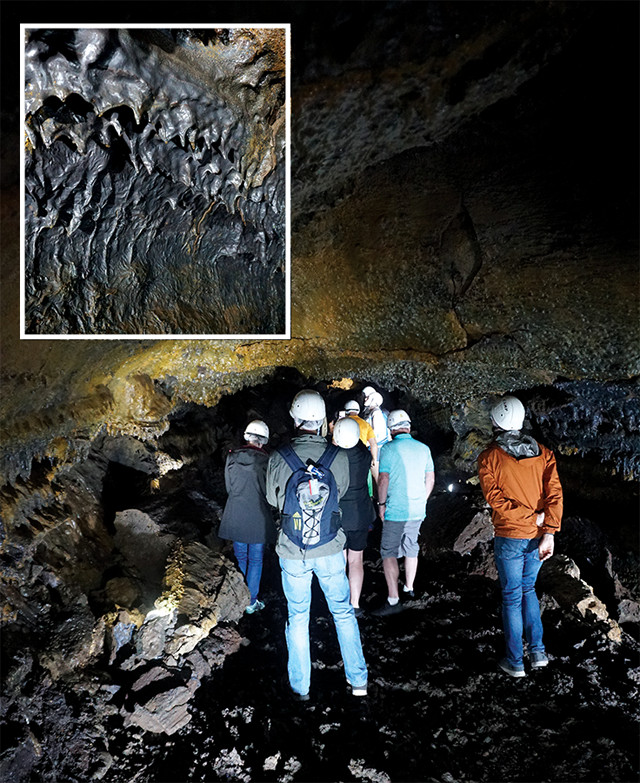

Tour guides lead groups through part of Gruta do Carvão, the longest lava tube in the Azores. Inside, visitors can marvel at the frozen textures of once-flowing lava. Credit: both: Kat Cantner and Colin McFadden.

São Miguel consists of six volcanic complexes, which have emerged and merged over geological time to form the island. Nordeste, the shield volcano on the east end of the island, rose from the seafloor about 4.1 million years ago. The shield volcano Povoação and the stratovolcano Furnas added mass to this new island through additional volcanic activity. Simultaneously, Sete Cidades rose out of the sea as an independent island to the west. The stratovolcano Fogo continued to add volume to the larger eastern island until the fissure eruptions of Picos finally joined the two islands into a single landmass.

The undulating coastline of São Miguel is dominated by the telltale twists and turns of basaltic lava flows. To get up close to these formations, visit Gruta do Carvão, a lava tube in Ponta Delgada. A short, guided tour takes you into the well-lit subterranean lava tube where you can listen to a brief geology lesson and marvel at the lava stalactites. After that, head out of town: Accessing the fascinating geology of São Miguel is as easy as taking a brief drive from the main city.

According to legend, the green and blue lakes of Sete Cidades were formed from the tears of a princess and a shepherd who were in love but forbidden to be together. In reality, the varied colors are due to an optical illusion based on differences in how the sun reflects off the lakes. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/peresanz.

Though lacking in native mammals of their own, the Azores have no shortage of dairy cows dotting the landscape (and occasionally blocking traffic). Driving out of Ponta Delgada through rolling green pastures, you’ll likely be greeted by some of the bovines who supply milk to the Azores’ dairy industry. Dairy is a big part of Azorean life, and big business in the archipelago, with many creameries producing a range of tasty cheeses, along with butter and other products, both for local consumption and export. The Azores, an autonomous region of Portugal, account for 50 percent of all Portuguese cheese production and about 30 percent of the country’s cow’s milk.

Effusive post-caldera forming eruptions produced cinder cones on the flanks of Sete Cidades. Credit: Kat Cantner and Colin McFadden.

On our first foray out of town, we headed for Sete Cidades Caldera, possibly the most photographed location on São Miguel. Sete Cidades is notable for the views of its caldera lakes, one of which appears green and the other blue due the angle of reflecting sunlight; it’s an optical illusion. The modern caldera shape is the result of three separate caldera-forming eruptions between 36,000and 16,000 years ago. The remnants of post caldera-forming eruptions are also evident on both the caldera floor, in the form of pumice rings, and on the outer flanks of the volcano, where steep-sided scoria cones lead down to the ocean.

Sete Cidades caldera was formed during three separate eruptions. Post-caldera forming eruptions are evident in the small pyroclastic rings on the caldera floor. Credit: Kat Cantner and Colin McFadden.

We parked near the Aqueduto do Carvão and set off along a 20-kilometer hike around Sete Cidades. The views were stunning, but as one of us is a recovering volcanologist, we were more interested in the layered pumice exposed along the trailside. This trachytic pumice occurs in poorly consolidated layers around the entire caldera rim where it has been colonized by an aggressive invasive ginger plant.

Loosely consolidated trachytic pumice lines the rim of Sete Cidades caldera. Credit: Kat Cantner and Colin McFadden.

After a long day of hiking Sete Cidades, take a short drive over to Ponta da Ferraria, the westernmost point on the island. There, geothermal springs flow into the ocean at the base of a cliff. Park at the top and clamber across the pahoehoe lava flows down the cliff, plunge into the chilly ocean water, and pull yourself along a rope to reach the geothermal outflow. For those with small children, or who are less willing to brave the swim through strong ocean waves crashing against sharp basalt outcrops, you can pay for access to a pool farther up the hill into which the geothermal water is pumped.

Adventurous visitors plunge into the basalt pool carved into the coastline where hot water flows into the chilly ocean. Credit: Kat Cantner and Colin McFadden.

Although the geothermal springs are the main attraction at Ponta da Ferraria, you can also see a well-marked pseudo-crater, or littoral cone, along the path to the springs that formed 840 years ago when lava flowed over the water-saturated surface. The underlying water flashed to steam, causing an explosion and the formation of a crater.

No site is as dear to the residents of São Miguel as Furnas, a town known for its bubbling cauldrons, hot springs and mineral-rich waters that have attracted people to the region since the 1600s. Furnas is a sprawling place with a lot to see, and you can easily spend a few days exploring this active volcanic complex.

Bubbling geothermal pools and mudpots surround the town of Furnas, which sits inside an active volcanic complex of the same name. Credit: Kat Cantner and Colin McFadden.

On the eastern edge of town, you can follow the smell of sulfur (or a map) to the geothermal pools, or caldeiras. Paved paths wind around the bubbling pools and vibrant bacterial mats. As if the sights and smells of the springs weren’t delightful enough, you can taste them too. Fountain taps along the road allow visitors to drink from a variety of natural springs, the most popular of which is cold carbonated water. To find the taps, look for a small white building with a red tile roof next to the bubbling hot springs. Formerly a bathhouse, this tiny structure currently houses OMIC, the Museum of the Microbial Observatory. A guide explains that the geothermal pools of Furnas are more microbially diverse than those of Yellowstone — a point of pride that is referenced repeatedly throughout the Furnas experience. The guide can set up a microscope for you with various bacterial and biofilm samples collected from the area. The small exhibit space also includes information on different extremophilic environments around the Azores and the world. At the end of the brief tour you can drink tea made with the thermal waters.

The main attraction at Furnas is the geothermal bathing in nearby Terra Nostra Gardens. The well-maintained gardens include a dazzling array of plants (if you can pull yourself away from the draw of the baths). Two bubbling hot tubs surrounded by lush vegetation lure in couples while, nearby, a massive pool invites families to splash and play. Be warned, the pool’s iron-rich water will turn any light-colored swimsuit dark orange.

The thermal pools are the most popular attraction at Furnas. Visitors can choose between the intimate hot tubs or the massive iron-rich pool. Credit: both: Kat Cantner and Colin McFadden.

As you wander through town after your soak, you’ll see signs for the local delicacy, cozidos, a large pot of onions, carrots, potatoes, cabbage, chicken, pork and beef that is buried in the hot earth in a geothermal area and left to cook for five hours. There is a public location along the north shore of Lake Furnas designated for cooking cozidos. This specialty is available at most of the local restaurants in town. Take note: Plates are extremely generous so it is wise to share.

Cooked by geothermal heat in deep pits (far left), the local specialty called cozido is a heaping pile of meat and vegetables. Credit: both: Kat Cantner and Colin McFadden.

On the southern shore of Lake Furnas, opposite the cozidos cooking spot, sits the Geopark Office/Furnas Monitoring and Research Center. The center includes a new exhibit with a time line of the history and development of the Furnas region, descriptions of different species of trees that grow nearby, and various rock samples from the region. The exhibit space is bright and informative, but you might want to skip the short film if you’re feeling drowsy.

On São Miguel, Furnas tops most visitors’ to-do lists, but our list additionally included a visit to the Volcanological and Geothermal Observatory of the Azores in the town of Lagoa. This museum is only open from 2:30 to 4:30 p.m. on weekdays with tours on the hour guided by graduate students. The museum is privately owned by Victor Hugo Forjaz, a volcanology professor at the University of the Azores and godfather of Azorean volcanology. In fact, his name appears on every publication in the bookshop associated with the museum.

Though understaffed, the museum presents an extremely well-curated narrative about the islands’ volcanic underpinnings and our guide was enthusiastic and knowledgeable. Guests enter through a reproduction of a lava tube, replete with ominous red lights and the sounds of an eruption. The exhibits begin with an introduction to general volcanology and the history of volcanic activity in the Azores, which is followed by a display of Forjaz’s extensive personal rock collection. The collection includes exquisite samples from each Azorean island, including fossils from Santa Maria, the only Azorean island featuring sedimentary rocks.

This wave-fed swimming pool is located at the bottom of a steep hike on the northeastern coast of São Miguel. Credit: Kat Cantner and Colin McFadden.

To connect with more of the cultural history of the Azores, travel along the north coast of São Miguel, where you can visit the only tea plantation in Europe, dating to 1883, see the 16th-century ruins of terraced milling operations, or visit Oficina-Museu das Capelas, a folk-art museum dedicated to the crafts of the Azores.

The northeast corner of the island also offers a glimpse of the oldest geologic history of São Miguel. Hiking trails through the remnants of the Nordeste shield volcano are littered with drill holes from geologists’ core samples. And if you remember to pack a swimsuit for the hike, you can bathe in one of the wave-fed pools at the base of the basalt cliffs.

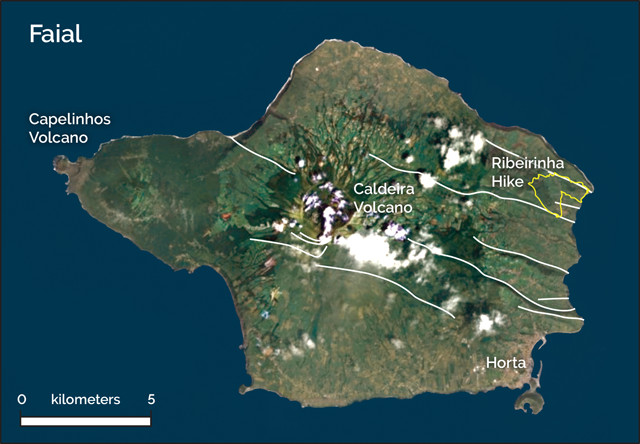

In the Central Group of the Azores, Faial sits on the Faial-Pico Fracture Zone, which is responsible for the large fault systems that span the island. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

Traveling within the Azores involves quick island-hopping flights. After five days exploring São Miguel, we took a small plane to Faial, one of the five islands in the archipelago’s central cluster. We landed in Horta, the main town on the island, with one goal: visit the volcano museum at Capelinhos, the site of the most recent volcanic eruption on the Azores. In 1957, a submarine eruption occurred off the coast of Faial, and after 13 months of continuous activity, a new peninsula at Capelinhos was born. The lighthouse, which once stood right on the coast, was the perfect observation station for geologists during the eruption. Now set back from the shore a little more due to the added land, the lighthouse is part of the Volcano Interpretation Center of Capelinhos, an impressive underground complex dedicated to the geology and history of this eruption. One of the significant effects of the eruption was the mass emigration of local residents to Massachusetts, Rhode Island and eventually California.

The lighthouse that once stood on the shoreline now overlooks the Capelinhos Peninsula formed during the 1965 volcanic eruption. Credit: Kat Cantner and Colin McFadden.

The Capelinhos eruption decimated the economy of Faial. Fields were covered in ash, and the docks that supported the whaling boats were rendered inoperable. Responding to concerns from their Portuguese constituents, Sen. John O. Pastore, D-R.I., and John F. Kennedy, D-Mass., spearheaded passage of the Azorean Refugee Act of 1958. An initial wave of 2,500 families settled mostly in New England, and in total approximately 175,000 Azoreans came to the United States between 1958 and 1980, settling mostly in New England and California.

The Capelinhos museum experience involves a three-dimensional movie that, rather dryly, details the origin of Earth and its atmosphere, oceans and islands, as well as galleries that focus on volcanoes and eruptions around the world, including the 1957 eruption of Capelinhos and those that came before it in the creation of the Azores. Unfortunately, a holographic animation of the Capelinhos eruption sequence was not working when we visited, but there are topographic models to explain the same content.

The museum tour ends with a visit to the top of the lighthouse, from which we could see trails leading up onto the flanks of Capelinhos. Back outside the lighthouse, we scrambled down the slope to what looked to be a trail map, only to find a warning sign advising against climbing the loose, gravelly slopes of the volcano. But the well-worn paths crisscrossing in every direction beckoned and suggested many others before us had explored the windswept and dusty landscape, and so we set off to do the same. After a thorough wander, we retraced our steps to the museum and climbed the crest above the lighthouse. It is easy to imagine the volcano rising from the sea from this vantage point. Capelinhos provides an amazing opportunity to see the ever-changing nature of Earth firsthand.

The largest city on Faial, Horta, serves as a waystation for yachts crossing the Atlantic Ocean. Crews paint their emblems along the seawall as tributes to their safe arrival. Credit: both: Kat Cantner and Colin McFadden.

The caldera of the central stratovolcano is the second-most popular attraction on the island, after Capelinhos. We had intended to hike there the following day but were deterred when the Rally of the Azores, a car race first held more than 50 years ago, was held on Faial that weekend, closing most of the major trails to hikers. Since most of the racing was taking place on the more popular double-track trails around the caldera, we decided to check out the faults on the eastern edge of Faial instead — after watching the race for a while of course. Rally car racing is a pretty fun reason to miss a hike and we enjoyed whooping and cheering along with the locals.

The original Ribeirinha Central Volcano has been obscured by faulting and successive volcanism, but remnants of the volcano can be found in the northeastern corner of Faial. We chose a hike that crossed back and forth across the Faial-Pico Fracture Zone in the hopes that bedrock would be exposed along one of the fault scarps. Although the trailhead for the Ribeirinha hike was easy to find, the dense native forest obscured the bedrock geology. However, signs of the geologic activity of the region were still visible. On July 9, 1998, a magnitude-6.2 earthquake struck the area and the nearby towns were left in ruin. The collapsed remains of the Ribeirinha lighthouse lie along the trail as a reminder of the continual geologic activity in the region.

Even the most geologically minded traveler cannot help but notice something else of significance to the island of Faial: yachts. The port of Horta is a stop-off for yachters sailing across the Atlantic Ocean, and visitors are welcome to wander the harbor, which is decorated with painted murals of yachts documenting their voyages. Although we tend to travel via airplane rather than yacht, we are certainly looking forward to returning to the Azores to explore the other islands of the archipelago.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.