by Terri Cook Tuesday, June 5, 2018

Just a few hours’ drive from London, along England’s southwestern shore, stretches a stunning expanse of coastline with a geologic story as captivating as its scenery. Thanks to a wide variety of landforms, impressive cliffs ranging in color from ochre to lily-white, and layered rocks representing all three periods of the Mesozoic Era, this 155-kilometer-long coastal strip has long been recognized as an important place in the study of earth science. But it’s the rich cache of fossils entombed within these colorful rocks, particularly those of Jurassic age, that led UNESCO to declare this singular shoreline a World Heritage Site in 2001. Exploring the “Jurassic Coast” — from its pebbly beaches, windswept walking paths and cozy pubs, to the various museums detailing the area’s long tradition of groundbreaking fossil discoveries — is a timeless and fun-filled adventure.

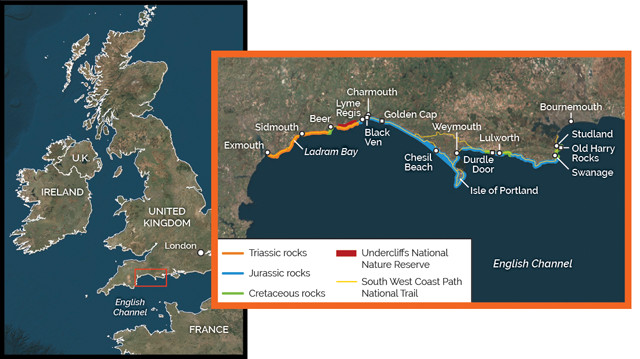

Stretching 155 kilometers along England's southwestern shore the Jurassic Coast features an array of dramatic landforms, cliffs and outcrops of Mesozoic rock, as well as bountiful fossils, all of which have contributed to its historical importance in the study of earth science. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

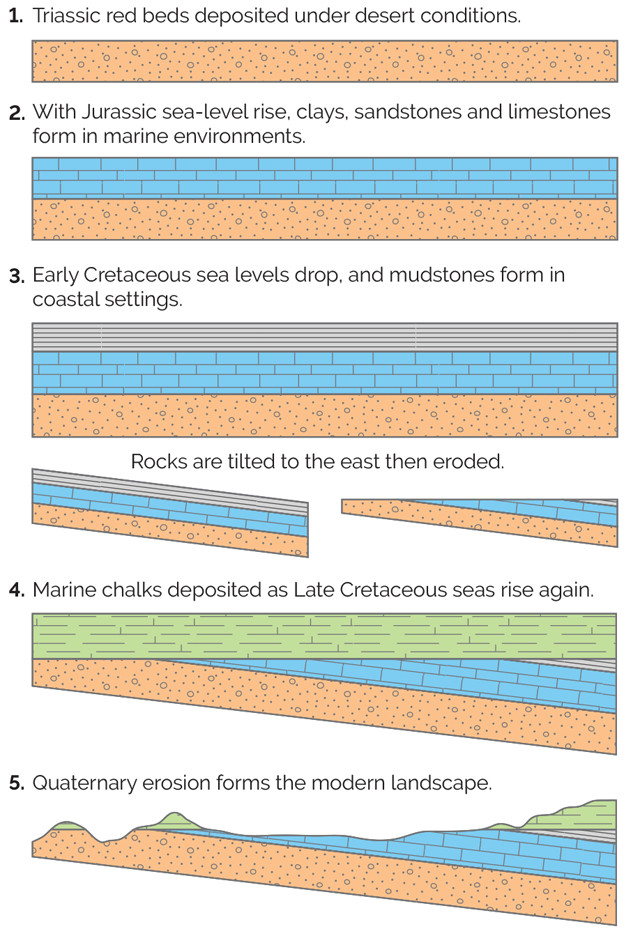

The rocks of the Jurassic Coast formed from layers of sediment that were deposited, tilted and eroded during the Mesozoic. More recent erosion, in the Quaternary, formed the coastal landscape as we know it today, leaving outcrops that represent roughly 185 million years of geologic activity. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

Situated along the undulating shoreline between the towns of Exmouth in East Devon and Studland in West Dorset, the Jurassic Coast is renowned for the nearly continuous 185-million-year record of Earth’s history exposed in its sensational seacliffs. These vibrant sedimentary rocks record one of the world’s best stratigraphic sequences from the Mesozoic Era, which lasted from 252 million to 66 million years ago and was distinguished by a rapid diversification of life as well as several major extinctions.

“Throughout this era, a series of sedimentary basins existed in the vicinity of the modern English Channel. In one of these, the Wessex Basin, whose rocks today cover more than 20,000 square kilometers of southern England, layer upon layer of sediment accumulated from the late Permian to the Paleogene. The sediments that filled the basin are several kilometers thick along portions of the Dorset Coast, and form three broad rock groups: a basal stack of Permian to Triassic “red beds”; a middle sequence of Jurassic to Early Cretaceous marine mudstones, sandstones and limestones that accumulated as the basin deepened in response to the rifting of Pangea; and an uppermost group primarily composed of Upper Cretaceous to Paleogene chalks.

“In the mid-Cretaceous, tectonic activity gently tilted the Mesozoic sedimentary layers down to the east. Then, sea level rose and Upper Cretaceous chalks, sands and clays accumulated atop the inclined layers. The contact between the top of the tilted section and these Upper Cretaceous layers is thus an unconformity. The time gap is larger to the west, where the underlying rocks are older than those to the east. Thanks to this fortuitous geologic happenstance, visitors can journey through 185 million years of Earth history while exploring the beautiful Jurassic Coast.

Sidmouth's seafront buildings contrast sharply with the ochre-colored cliffs of Triassic rocks that rise nearby. Credit: ianwool/istockphoto.com.

Triassic rocks extend eastward from the World Heritage Site’s western boundary at Exmouth, where seasonal Jurassic Coast Cruises provide excellent views of the coastal exposures. Between this port and the resort town of Sidmouth, the sinuous shoreline is distinguished by dramatic, ochre-colored cliffs that rise sharply from the restless English Channel to form rugged promontories and isolated sea stacks.

A great place to see the Triassic portion of this coastline up close is at Ladram Bay. About 4 kilometers southwest of Sidmouth, a holiday park offers boat rentals, a clifftop restaurant with lovely views, and beach access to the Pangean red beds. Whether you view these sandstones from land or sea, their most distinctive characteristic is a deep crimson color, imparted by the relatively large amount of ferric iron oxide minerals in the rock. The red beds and other clues, including the presence of evaporite minerals like gypsum and halite elsewhere in the Triassic section, indicate these sediments were deposited in a hot, arid environment when the region lay locked in the middle of the supercontinent.

“Pangea’s center, however, was far from homogenous; lakes, lagoons and fields of sand dunes created a shifting patchwork of depositional environments where the more than 1,100-meter-thick Triassic section accumulated for tens of millions of years. Despite the overall dryness of the environment, crossbeds visible in the colorful cliffs and sea stacks at Ladram Bay provide evidence that large rivers periodically flowed across this region. These rivers drained a tall mountain range to the west that was uplifted roughly 100 million years earlier during the Carboniferous Period as the assembly of Pangea was finalized. Due to their terrestrial origins, the Triassic rocks host relatively few fossils, but those that have been found in this region — including 10 species of reptiles, fish and amphibians discovered in mid-Triassic rocks west of Sidmouth — are of international importance.

The most famous — and namesake — portion of the Jurassic Coast is its central segment, which stretches east from the historic town of Lyme Regis and showcases one of the world’s most complete marine sequences from the Jurassic Period. Deposited in the depths of the Wessex Basin in environments ranging from deep water to coastal lagoons, this stratigraphic section consists of rhythmic layers of mudstone, sandstone and limestone that preserve six cycles of rising and falling sea levels.

“The Jurassic section is best known for its remarkable fossil record, which is inextricably linked with the story of Mary Anning. Born in Lyme Regis in 1799, Anning overcame her low social status, lack of formal education and poverty to become one of England’s greatest fossil hunters. In her book, “Jurassic Mary,” author Patricia Pierce narrates how, as a child, Anning accompanied her father, a carpenter, on coastal walks in search of fossils he could sell to supplement his meager income. After her father’s death in 1810, Anning continued to walk the shoreline near Lyme Regis, where frequent landslides and harsh winter storms would often expose new fossils.

This whimsical 1863 engraving depicts an ichthyosaur and a plesiosaur, both apex predators in Jurassic seas. Credit: Edouard Riou, engraved by Laurent Hotelin and Alexander Hurel.

You can learn more about Mary Anning and walk in her footsteps in the village of Charmouth, a few kilometers east of Lyme Regis. There, the free Charmouth Heritage Coast Center has informative exhibits about her and other locals’ many fossil discoveries, including Scelidosaurus, the “Charmouth Dinosaur.” This armored herbivorous dinosaur, which roamed the region about 190 million years ago, grazed on grasses that grew on islands sticking out of the tropical Jurassic sea. The fossil cast on display at the museum was fashioned from the best preserved of the eight Scelidosaurus skeletons found in this area.

Because the soft, gray cliffs that line the sea near Charmouth are chock-full of fossils, the beach by the heritage center is considered the best place in the World Heritage Site to go fossiling. When the weather and tides cooperate, it’s fun to stroll near the pounding surf, searching among the “shingles” (beach stones) for bullet-shaped belemnites, coiled ammonites and other strange-looking creatures that once swam “n the Jurassic seas. You’re allowed to keep your finds as long as you follow the local fossil collecting code.

The combination of alternating layers of soft mudstone and more resistant sandstone, the wet weather, and erosion of the base of the seacliffs have made the coast’s Jurassic section notorious for landslides. Major mudslides have occurred repeatedly just west of Charmouth at Black Ven, where Anning found the famous Plesiosaurus skeleton. She also witnessed the aftermath of the “Great Landslip” of Christmas 1839, which occurred west of Lyme Regis along the stretch now preserved as the Undercliffs National Nature Reserve. The slide involved the breakaway of a large, intact block of land, which also formed a small temporary harbor. The changes dramatically reshaped the local landscape and attracted attention from tourists as well as the eminent scientists William Buckland and William Conybeare, who studied the 1839 event in detail and penned some of the earliest known scientific descriptions of landslides.

Frequent landslides have shaped the Jurassic Coast, creating inspiring scenery and important wildlife habitat — and sometimes causing considerable destruction. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Repeated landslides in this area have created a mosaic of habitats that constitute one of Britain’s most crucial wilderness areas. And slides continue to reshape this coastline today, frequently damaging portions of the 1,014–kilometer-long South West Coast Path, the U.K.’s longest national trail. Nine segments of this popular route, which follows the South West Peninsula coastline, traverse the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site.

Repeated landslides in this area have created a mosaic of habitats that constitute one of Britain’s most crucial wilderness areas. And slides continue to reshape this coastline today, frequently damaging portions of the 1,014–kilometer-long South West Coast Path, the U.K.’s longest national trail. Nine segments of this popular route, which follows the South West Peninsula coastline, traverse the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site. Quarried since Roman times, this high-quality limestone is composed of oolites — round grains of concentrically layered calcium carbonate — deposited near the end of the Jurassic in balmy, lime-rich waters similar to those found today near the Bahamas. This durable material has been used to construct a number of prominent buildings in London, as well as the United Nations’ headquarters in New York City.

Isle of Portland is also a famous fossil locality for Late Jurassic fish, turtles and ammonites, and it hosts a Fossil Forest that once grew alongside a hypersaline lagoon that existed during a time of sea-level regression. Boat trips from Portland Harbor and the small city of Weymouth are seasonally available to the island, where you can visit the historic Tout Quarry, which has been converted into a sculpture park and nature reserve. The isle also boasts several lighthouses; outdoor recreation including rock climbing, kayaking and hiking; and opportunities to view native butterflies and orchids, which bloom from late spring through early summer.

East of the Isle of Portland, between the towns of Weymouth and Lulworth, the seacliffs are composed of Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous rocks. Sea levels fluctuated during this time, and the region hosted a variety of coastal environments, including sabkhas — coastal lagoons covered in salt flats like those found today around the Persian Gulf — as well as verdant swamps inhabited by Iguanodon and other dinosaurs. As sea levels rose later in the Cretaceous, the region was submerged beneath a sea teeming with microscopic algae. When these organisms died, their calcium carbonate shells gradually accumulated on the ocean floor, forming a thick layer of carbonate-rich ooze that later lithified into snow-white chalk.

The pale cliffs of Old Harry Rocks formed from the remains of microscopic algae that thrived in the ocean that covered this region during the Late Cretaceous. Credit: milangonda/istockphoto.com.

This porous chalk forms the spectacular scenery at Old Harry Rocks, a trio of rock formations that mark the Jurassic Coast’s easternmost point. These rocks, which erosion has isolated from the narrow coastal headland, are best viewed from boats departing out of Swanage or Bournemouth, from along the South West Coast Path, or from the shores of South Beach. South Beach is reached by a short path that heads downhill from the Bankes Arms, a cozy stone pub that serves up pints of house-brewed ale to customers gathered around a crackling fire.

Scraps of Upper Cretaceous rock overlying the unconformity are also present in several other locations along the coastline, including the upper cliffs east of Sidmouth, where the white limestone contrasts sharply with the underlying Triassic red rocks. Some Upper Cretaceous rock is also present near the town of Beer, where downward faulting of a large block of chalk protected it from erosion. In this area, a layer composed primarily of shell fragments has been extensively quarried to provide building material for 24 cathedrals and Windsor Castle. Although active quarrying ceased in 1920, visitors can still tour the extensive Beer Quarry Caves from late March through late September.

Two more iconic Jurassic Coast sites are Durdle Door, a classic sea arch, and horseshoe-shaped Lulworth Cove, both located, geographically, about 15 kilometers east of Weymouth, and geologically, near the Jurassic-Cretaceous stratigraphic transition. The features owe their origin to an especially resistant band of Portland Stone, which has better resisted the waves’ erosional onslaught than the adjacent softer rocks. Lulworth Cove formed after a stream eventually broke through the resistant band of Portland Stone, which had formed a bulwark against the sea. This breach then allowed waves to hollow out the soft clays inland of the strong limestone, creating the famous embayment. Similar processes formed Durdle Door, creating yet another site where visitors can relish the Jurassic Coast’s tantalizing combination of gorgeous scenery, landmark attractions, and 185 million years of incomparable evolutionary history.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.