by Naomi Lubick Monday, June 11, 2018

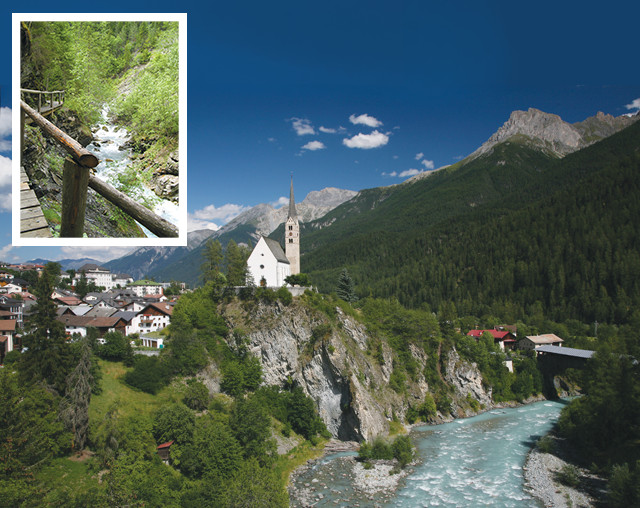

A church in Scuol overlooks the Inn River. The mountains that loom over the Lower Engadine Valley were uplifted when the African Plate overthrusted the European continent more than 100 million years ago. Inset: One of the trails through the Lower Engadine Valley. Credit: ©Daniel Schwen, Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic; inset: Naomi Lubick

Credit: AGI/NASA

Standing on the dark rocks beneath the small Swiss town of Scuol, you can look up into the surrounding chalk-white mountains and see the view from Europe to Africa. Or rather, you can gaze from the European continental rocks that pave the valley to the mountains above, which are made up of what was once the African Plate, before tectonic forces pushed it up and over the European continent.

This is the basic tectonic story behind the forces that have shaped the Lower Engadine Valley, nestled in the southeastern Swiss Alps, for millions of years. The Engadine has also been shaped by a major fault that runs parallel to the valley, as well as a large anticlinal fold and multiple glaciations. This history makes the valley an ideal tourist destination for geo-fans; it’s home to excellent alpine hiking and mountain biking trails, not to mention ski slopes and alpine ski touring loops if you visit in winter. The geology is also responsible, of course, for Engadine’s famed mineral baths.

During the summer, hikers in the Lower Engadine are likely to come across one of the valley's numerous cows. Credit: ©Daniel Schwen, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

The Engadin Bad Scuol is home to a variety of spa treatments, including Irish-Roman baths, as well as outdoor swimming pools. Credit: swiss-image.ch/Christof Sonderegger

The view from a trail on the north side of the Inn River, near Scuol. Credit: Naomi Lubick

The resort town of Scuol, with a population just over 2,200, is centrally located in the Lower Engadine Valley and is the best home base for any visit. The town is a few hours’ train ride from Switzerland’s cosmopolitan banking city, Zürich, and is home to a variety of accommodations, from luxurious spas to a simple, modern-chic hostel.

Staying in Scuol means that you’re in Europe, but surrounded by mountains from Africa, says Matthias Merz, a local geologist who consults for construction projects. Limestones and other deep-sea sediments that deposited in the ancient Valais Ocean, part of the Tethys Ocean that sat between Africa and Europe about 100 million to 50 million years ago, were pushed up into the mountains when the African continent overthrusted the European continent. The plates’ convergence started in the Early Cretaceous period, more than 100 million years ago, and the mountain-building, or orogeny, continues today.

Merz compares the pileup to two stacked books, with the pages progressing from start to finish, and then start to finish again: A sequence of older to younger European limestones rests on the bottom of the valley with a sequence of older to younger African dolomitic and calcitic rocks on top. Today the European rocks are largely exposed within the valley, where erosion has cut a hole through the African deposits.

Several geologic forces worked together to create this 55-kilometer-long, 17-kilometer-wide “window” to Europe’s past, called the Engadine Window. First, the confluence of the seismically active Engadine Line — a strike-slip fault that runs parallel to the valley on its southern edge — and the steady flow of the Inn River, which runs west to east down the Lower Engadine, eroded a large gorge that snakes up into the mountains. Then, multiple glaciation events that have ebbed and flowed through the valley every 10,000 to 20,000 years enlarged the gorge by removing even more rocks. The last glaciation receded about 10,000 years ago, Merz says.

The huge expanse of the Engadine Window contains hiking and biking trails, and a famous loop known as the Engadine Trail or Via Engadina, a trail that allows visitors to walk from village to village in the valley. You can do it on your own, or hire the local tourism bureau to help carry your bags; a seven-day walk costs roughly $400.

The small town of Unterterzen sits along the shores of Walensee (Lake Walen). Visitors can take a boat ride on the lake and enjoy the mountain views. Credit: ©Adrian Michael, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

The complicated geology of the Alps is on full display along the valley’s well-marked trails, with accretionary wedges, high-pressure and high-temperature metamorphism, faults and amazing folding of the geologic layers. For example, the trails that cross the alpine slopes on the north side of the Inn River give you views across the Lower Engadine to folded and smooshed rocks in the metamorphosed mountains on the opposite side, and you can cross the contacts between massive limestones and folded sedimentary layers in some places.

This building in a small town near Scuol shows the decorative technique called "sgraffito," which adorns many structures in the Lower Engadine Valley. Credit: Naomi Lubick

The Swiss National Park, Switzerland’s only national park, is located on the southern edge of the valley, south of Scuol. Val Mingèr, a valley between Scuol and the village of S-charl, makes an excellent entrance point to the park to the south. To enjoy a good steep valley hike, walk the trail through Val Triazza; the trail follows the valley’s stream as it flows north into the Inn River at Scuol. In June, this valley is dotted with purple and yellow lady slipper orchids. For a more leisurely stroll, follow the Scuol-to-Sent walking/biking path on the north side of the Lower Engadine Valley; it’s a wide, unpaved road with a view that covers some elevation, but it’s not as steep as the slopes to the south of the Inn River. You can download or order maps for these paths from the local tourism bureau (www.scuol.ch).

Consider taking a Post Bus (yes, it really is run by the Swiss National Post Office, which also runs a bank) from Scuol to other nearby villages for the start of some afternoon or day hikes. Davos and St. Moritz are also not far away, should you want some Swiss village glamour.

The spas in the region add to the glamour, thanks to a huge anticlinal fold in the Lower Engadine Valley that helped create geothermal springs. The A-shaped fold provided the capstones that trapped groundwater in lenses at the anticline’s center, Merz says, as well as the rock conduits that bring the springs to the surface.

Most of the water in the springs around Scuol spends about five years percolating in the shallow groundwater system before popping up at the surface, full of carbon dioxide and usually some sodium or calcium carbonate minerals. But the waters that percolate more deeply can spend decades underground; the deeper the water travels, the more salts it brings up with it.

That pressurized groundwater is the source of the famous mineral springs that made Scuol a bather’s destination, beginning in the mid-1300s. The mineral waters’ allure eventually led to the construction of grand hotels and baths in the mid-1800s, which once drew people for “wellness” treatments from across Europe. The baths remain a major draw to the region today, and are a great way to soothe achy backs and legs after a mountain hike or bike ride. The main baths are at Engadin Bad (bath) Scuol, in the center of town; during holidays and summer vacation months, make sure you have reservations, which can be made through the spa’s website (www.cseb.ch/Bad-de/AktuellesBad).

View of the Swiss Alps from the ski resort Flumserberg. Credit: Naomi Lubick

But a trip to the Lower Engadine Valley, and to Scuol in particular, is more than just a trip through Switzerland’s geologic history. Switzerland has four official languages: German (with many Swiss variants), French, Italian and Romansch, a language that splits into five main “idioms” and several more dialects in the tiny Engadine region. The mix of Italian in this Latin-derived language may not be a surprise, considering how close Italy is — just across the alpine mountain range — at this far eastern edge of Switzerland.

The local food strikes the right mix between Swiss-German and Italian. A plate of “spätzli” (or “pizokel” in Romansch), an elongated gnocchi-shaped pasta, from the restaurant Crusch Alba (Romansch for “White Cross”) in the heart of Scuol will give you a taste of the hearty mountain meals typical of the region. Another typical product is Graubünden beef, hung to dry in high alpine sheds and pressed into rectangular logs.

Another local specialty is a decorative technique known as sgraffito. Artists scratch designs with a nail or other sharp implement into fresh patches of cement applied high up near the eaves of a building, tracing patterns local to the region, Christian symbols and biblical texts, or philosophical tales, for example.

Depending on how much time you have for your travels, consider stopping for an afternoon on the Walensee (Lake Walen) on your way back to Zürich. From the small town of Unterterzen, you can take a gondola ride up to the ski resort Flumserberg, and experience the mountaintop restaurant’s panoramic view (on good days you can see all the way to Zürich, just shy of 100 kilometers away), or from the shores of Unterterzen, take a boat ride on the lake to enjoy the view of the surrounding mountains’ looming rock faces etched with massive folds — the remaining evidence of the immense metamorphic and orogenic forces that shaped the Swiss Alps.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.