by Terri Cook and Lon Abbott Friday, August 19, 2016

The so-called jade islands of Ha Long Bay in Northern Vietnam are the embodiment of karst topography. More than 1,600 islands pierce the emerald-green water. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Nikada.

Early in Vietnam’s history, the country was repeatedly attacked by enemies arriving by sea. According to Vietnamese legend, the mythical Jade Emperor, who felt sorry for the Vietnamese people, sent the Mother Dragon and her children to Earth to help them defend their land. When enemy ships next approached, the dragons descended from the sky and spat countless giant pearls into the ocean. These magically turned into a multitude of jade islands, which linked together to create an invincible barrier that barred the approaching ships and caused them to crash and sink beneath the waves. Following the battle, the Mother Dragon and her children were so enthralled by the bay’s beauty that they decided to remain on Earth rather than return to heaven. To remember the dragons’ help, the local people named one bay Ha Long, which means “descending dragon,” and a bay to the northeast, where her children descended, Bai Tu Long, which means “thanks to the Dragon’s children.”

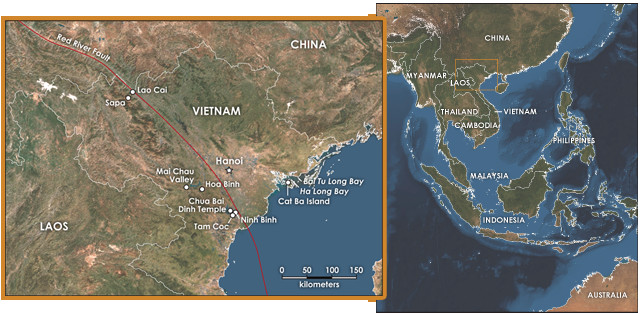

Geologists, of course, know these islands and bays — situated just off Vietnam’s far northern coastline — as embodiments of karst topography, and a worthy stop on any geotraveler’s itinerary. Hanoi, the country’s chaotic capital city, is an ideal base from which to explore Northern Vietnam’s magical scenery and experience the legendary hospitality of the gracious Vietnamese people.

Northern Vietnam abuts southern China. The 1,000-kilometer-long Red River Fault, which is Northern Vietnam's dominant tectonic feature and forms part of the geological boundary between Northern and Southern Vietnam, passes through Ninh Binh. Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI.

“Northern Vietnam is the most rugged and scenic part of one of the world’s most exotic countries. The recipe for this scenic splendor calls for just three simple ingredients: abundant limestone, vigorous recent tectonic activity, and a tropical climate. The first ingredient, a blanket of limestone up to 3 kilometers thick, accumulated during an extended, 130-million-year span from the Mid-Devonian through the Early Triassic, when the South China crustal block, to which Northern Vietnam belongs, was submerged beneath the ocean. The rest of Southeast Asia was appended to the South China block in a complex series of collisions with microcontinents during the Indosinian Orogeny, 250 million to 240 million years ago.

The second ingredient — vigorous recent tectonic activity — began to roil the region about 40 million years ago, when Northern Vietnam again rumbled to tectonic life with the intrusion of granites and the onset of major faulting. The 1,000-kilometer-long Red River Fault is Northern Vietnam’s dominant tectonic feature. The Red River, which follows an exceptionally straight course through the country, passing through Hanoi en route, lent its name to the fault, which has been moving with right-lateral motion for the last 5 million years. (Right-lateral motion means that, to someone looking across a fault line, the rock on the opposite side appears to move to the right.) Prior to that time, the fault moved in the opposite direction.

The recipe for the scenic karst pillars of Northern Vietnam involves abundant limestone, vigorous tectonic activity and a tropical climate. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

This reversal of slip direction is at the root of a spirited geological debate about the degree of linkage between Vietnamese tectonics and the Himalayan collision. Some geologists argue that, as the battering ram that is India collided with Asia beginning about 50 million years ago, the Red River Fault accommodated between 500 and 1,000 kilometers of eastward extrusion of Southeast Asian rock as it escaped the collision zone. That led to left-lateral motion as Southeast Asia slid to the east relative to South China. But as India continued to collide with Asia, part of South China, in its turn, was forced from the collision zone, sliding eastward relative to Southeast Asia and thereby changing the Red River Fault’s slip direction to right-lateral.

Other scientists disagree, arguing that geologic evidence indicates that no more than 50 kilometers of slip have occurred along the fault. Regardless of which hypothesis is correct, movement along the Red River and companion faults has jumbled the surrounding blocks of marine limestone, tilting and folding them in complex ways and ultimately making them more susceptible to dissolution.

Cat Ba Island is a popular adventure travel and ecotourism destination for rock climbing, cliff jumping, snorkeling and scuba diving. Credit: both: Nick and Claudia, butforthesky(dot)com.

When bathed in groundwater, limestone easily dissolves, creating distinctive karst topography. Because this dissolution is speedy in Vietnam’s warm, tropical climate — the third and final ingredient needed to create Northern Vietnam’s legendary scenery — the area’s once-continuous blanket of limestone became riddled with caves until the subterranean texture resembled something like Swiss cheese. The cave roofs eventually collapsed, creating sinkholes, and ultimately, the bedrock left undissolved and still standing comprised landscapes of limestone spires. Northern Vietnam and southeastern China constitute the world’s largest (and, many would argue, the most spectacular) karst region, which visitors can easily access at several stunning locations.

A highlight of a river tour up the Ngo Dong River is gliding through a narrow karst tunnel where the cave roof is roughly a meter above the water line. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Vietnam’s karst crown jewel is Ha Long Bay. At this stunning UNESCO World Heritage site, the bay’s emerald-green water is pierced by more than 1,600 islands, most of which consist of dramatic limestone towers, the tallest of which soar 400 meters above the water. The legend of the Mother Dragon was the way that earlier generations of Vietnamese explained the formation of this incomparable bay, whose islands are evocatively named for their shapes, such as Bach Long Vi island, which means “the place where the dragon children wiggled their tails violently to make white foam.” Although the modern explanation — corrosive groundwater slowly dissolving away beds of limestone — might not be as romantic as the dragon legend, a modern geologist’s heart quickens when admiring the grandeur that slow, subtle geologic processes have wrought.

The best way to enjoy Ha Long Bay’s splendor is on an overnight cruise aboard a “junk,” a sailing vessel with a distinctive scalloped sail that has been plying the waters of Southeast Asia since the second century. A one-night trip will give you a taste of the spectacular scenery, but if you have enough time and prefer to enjoy this scenery without as many crowds, consider taking one of the day-long Lan Ha Bay cruises, which leave from Cat Ba Island, the bay’s biggest isle. Even farther off the beaten path is Bai Tu Long Bay, the bay created by the dragon children, which is a five-hour boat ride from Ha Long Bay.

Ha Long Bay is best explored via water. Take an overnight cruise aboard a "junk," a sailing vessel with a scalloped sail that has been gliding the waters of Southeast Asia for almost two millennia. Credit: William J. Ervin.

“Cat Ba Island is an adventure travel and ecotourism mecca, attracting beach combers, sailors, snorkelers, scuba divers, rock climbers, hikers, bikers and birdwatchers. Much of the island lies within the borders of Cat Ba National Park, created to preserve its verdant scenery and diverse ecosystems. The protected inhabitants include the golden-headed langur, purportedly the world’s rarest primate. Those interested in Vietnam War history will also want to tour Hospital Cave, used by the Viet Cong during the war as a secret, three-story, bomb-resistant hospital, located about 10 kilometers north of the town of Cat Ba on the road to the national park.

The karst spires near Ninh Binh are similar to those of Ha Long. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

“Back on the mainland, the karst spires of Tam Coc, 9 kilometers southwest of the city of Ninh Binh, are similar to those of Ha Long, but without the bay. The abundant sediment transported by the Red River has created a large delta with Hanoi at the apex. The delta separates the karst areas — Ha Long to the north and Tam Coc to the south. You can peddle through the karst on a rented bike or tour it on a delightful two-hour boat ride up the Ngo Dong River, piloted by local boatpeople who push and steer the oars with their feet. Either way, you’ll pass lush rice fields tucked beneath dramatic limestone cliffs, fishermen angling in the shallow river for tonight’s dinner, and smiling children herding flocks of ducks to the market. The highlight of the boat trip, however, is gliding through a narrow karst tunnel where the cave roof rises just a meter or so above the water line.

Ninh Binh lies just northeast of the Song Ma Fault, a linear belt of distinctive rocks that marks where the Southeast Asian terranes were sutured to the South China block during the Indosinian Orogeny. Although the former political boundary between Northern and Southern Vietnam lies farther south, along the former demilitarized zone, Ninh Binh lies along the geological boundary between Northern and Southern Vietnam.

Other tourist attractions near Ninh Binh include Hoa Lu, the location of Vietnam’s capital during the late 10th century, as it was naturally protected by the craggy karst mountains. Also worth visiting in this area is the Chua Bai Dinh, a huge Buddhist temple complex boasting an impressive 13-story pagoda, as well as Vietnam’s largest bell, a 10-meter-tall bronze Buddha, and the stone statues of 500 enlightened Buddhist practitioners known as arhats.

Locals push and steer boats with their feet. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Sapa, the tourism center of northwestern Vietnam, clings to a steep hillside covered with lush rice terraces frequently wreathed by mist from rain showers. It was founded in the early 20th century as a hill station by the French colonial powers as an escape from the summer heat for the expat bureaucrats due to its cool, 1,650-meter-high elevation. Sapa is reached by a steep, twisting, one-hour bus ride from Lao Cai, which lies along the Red River Fault just 3 kilometers from the Chinese border, and at a mere 91 meters elevation. Colorfully dressed women from the many different local ethnic minority hill tribes, with the Hmong the most numerous, greet each bus, hoping to help passengers carry their bags to their accommodations for a small tip. You can spend many delightful hours wandering Sapa’s colorful market, and the town is a great trekking base from which to visit hill-tribe villages and admire the spectacular scenery. One worthwhile destination is the Sapa Ancient Rock Field, a field in the beautiful Muong Hoa Valley strewn with boulders adorned with ancient petroglyphs depicting people, animals and geometric shapes. Archeologists know little about the carvings, which may date to between 3,000 and 4,000 years ago.

Sapa clings to a steep hillside covered with rice terraces. Credit: William J. Ervin.

On a clear day, from your perch on the Sapa hillside you can gaze southwest across a precipitous, linear valley at the soaring peaks of the Fansipan Massif, which contains Vietnam’s highest peak at 3,143 meters elevation. A left-lateral strike-slip fault runs through the valley. It juxtaposes rocks of the Sapa metamorphic complex, dominated by marble, with the 35-million-year-old granite of the massif.

In Hoa Binh Province, rice paddies blanket the lowland valleys of the Da River and its tributaries with karst peaks forming a stunning backdrop. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

An alternate destination for an intimate glimpse of hill-tribe life less than 100 kilometers from Hanoi is Hoa Binh Province. The province is sprinkled with more than 50 villages designated by the Vietnamese government as “ethnic tourism hamlets,” populated by members of the Muong, Thai, Yao, Tay and Hmong ethnic groups. Whereas at Sapa the terraced fields cling precariously to steep mountainsides, here, bright green rice paddies blanket the lowland valleys of the Da River and its tributaries, with nearly vertical karst peaks framing the backdrop. During our visit to the Mai Chau Valley, we stayed in Lac village in a guesthouse raised on stilts and drank the unique local rice wine, which is brewed with forest leaves and traditionally sipped through meter-long straws from a communal clay pot. We also took a delightful sunrise trek through the mist-shrouded rice paddies, enjoying the cool morning air and watching the locals go about their daily work in the fields.

On a clear day, Fansipan Massif is visible from Sapa. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Hanoi is the hub from which Northern Vietnam’s geologic highlights are all easily accessible. But Hanoi is much more than just a transportation hub; it is a major tourist destination in its own right. The most astounding thing you are likely to do in this crowded, chaotic city is cross the street while shopping in the historic Old Quarter. Even when the “walk” light is illuminated, you must boldly venture into the road, maintaining a steady pace so that the drivers of the myriad buzzing motor scooters can accurately assess which way to steer to avoid you. You’ll find the streets of the Old Quarter are named for the wares sold on each, and you can bargain for the best price among numerous vendors all selling the same items. We toured “Tool Street,” “Kitchen Street” and “Silk Street,” once we summoned up the courage to cross the street! There are plenty of other attractions as well, including several temples, Ho Chi Minh’s Mausoleum, and the museum of the Hoa Lo Prison, otherwise known as the infamous “Hanoi Hilton,” where U.S. prisoners of war were held during the Vietnam War. The museum offers an opportunity for a visiting Westerner to glimpse the Vietnam War from the other side.

Shopping in the Old Quarter of Hanoi is quite an experience, negotiating traffic and people and bargaining with vendors. Credit: clockwise from top left: ©iStockphoto.com/Nicola Ferrari; William J. Ervin; Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

“After admiring Northern Vietnam’s gorgeous karst, soaring mountains, and bustling cities, you may be so enthralled with the landscape and its friendly people that — like the Mother Dragon and her children — you’ll find it difficult to leave.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.