by Terri Cook and Lon Abbott Tuesday, December 18, 2018

No visit to the windswept Tibetan Plateau would be complete without seeing Mount Everest, the world's highest peak. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

Few destinations are as alluring as the wild and windswept Tibetan Plateau. With an average elevation of 4,500 meters, it is Earth’s highest tableland and one of the most isolated regions on the planet. Tibet’s capital, Lhasa, one of the world’s highest cities, is simply breathtaking — both literally, given the low oxygen levels at this altitude, and figuratively, with its mountainous backdrop and the gleaming whitewashed walls of Potala Palace, an enduring symbol of Tibetan Buddhism, rising high above the Old Town. As we saw firsthand when our family visited last summer, Lhasa — with its intricately painted statues, gilded-dome stupas housing Buddhist relics, and thousands of prayer wheels glistening in the flickering light of yak-butter candles — is a place that’s both above and apart from the rest of the world.

As magical as Old Lhasa is, no trip to Tibet, officially called the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, would be complete without also experiencing the surrounding countryside. On a four-day excursion from Lhasa, you can cross the Eurasian-Indian collision suture zone, admire the sparkling turquoise waters of sacred Yamdrok Lake, tour hidden monasteries belonging to different Buddhist sects, and marvel at Mount Everest, the world’s tallest mountain.

Lhasa is tucked in a flat river valley with peaks rising nearly 2,000 meters on either side. And with the city itself at an elevation of 3,700 meters — making the climate balmy by Tibetan standards — you pass through field after field of cold-tolerant barley, one of the few crops that can be widely grown on the Tibetan Plateau, while approaching Lhasa. These fields then abruptly yield to tracts of ugly concrete apartment blocks, the result of explosive growth produced by China’s “Great Western Development Strategy” instituted in 1999, the year we last visited Tibet. At that time, independent travel was allowed, but now, foreigners must prearrange a tour, which includes transportation and a guide who accompanies you everywhere.

Barkhor Square is the heart of Lhasa's bustling commercial district. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

city’s population has grown by more than 100,000 since our last visit; today, 330,000 people call Lhasa home. Although the new parts of Lhasa are architecturally identical to hundreds of Chinese cities, the Barkhor, the Old Town area built around the Jokhang, Tibet’s most important Buddhist temple, has a storied history and a more traditional Tibetan ambiance.

a was established as the capital by Songtsen Gampo, the leader who unified Tibet in the seventh century. To solidify his reign, Gampo arranged strategic marriages to Nepal’s Princess Bhrikuti and China’s Princess Wencheng, both of whom hailed from Buddhist countries. As part of their dowries, both brought important Buddhist statues that the Jokhang was built to house.

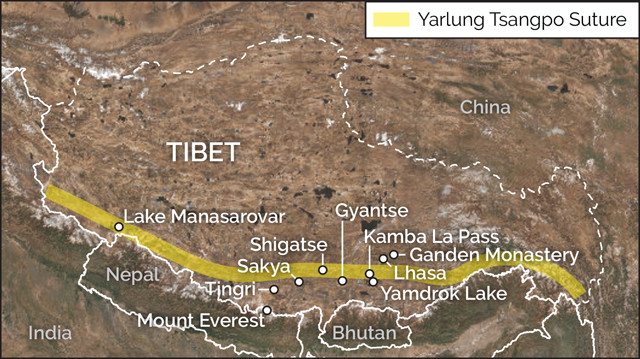

The southern border of Tibet lies along the Yarlung Tsangpo Suture, the fault zone that forms the boundary between the Eurasian and Indian plates. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

ass=““caption”>Historians consider these Buddhist princesses to have been influential in Songtsen Gampo’s decision to establish Buddhism as Tibet’s state religion, which remains the central pillar of Tibetan life. This is evident when you join the throngs of pilgrims performing the 1-kilometer circumambulation of Jokhang, winding through a maze of narrow alleys that open onto the expansive Barkhor Square. The pilgrimage route passes through the heart of Lhasa’s commercial district, creating an intoxicating scene that combines shouting merchants, bustling noodle stalls, chatting locals and colorfully dressed pilgrims from the far corners of Tibet slowly inching their way around the circuit, prostrating themselves after each and every step.

ddition to the Jokhang, Lhasa hosts three of the most important monasteries of the Gelug (Yellow Hat) Sect of Tibetan Buddhism, which is led by the Dalai Lama, who is also Tibet’s traditional secular ruler. Two of the monasteries, Sera and Drepung, are usually included in Lhasa city tours; the third, Ganden Monastery, is about 50 kilometers from the city. Drepung Monastery is built on the lower slopes of Mount Gephel, which offers panoramic views of the Lhasa River Valley, including the city and Potala Palace. In addition to offering a wonderful cultural experience, the monastery is an especially good place to examine Lhasa’s geologic setting.

The uplift of Tibet occurred along with the Himalayan Orogeny, beginning when India first collided with Asia about 50 million years ago. Prior to this collision, oceanic crust of the Tethys Ocean was being subducted beneath the Lhasa Terrane, Asia’s southernmost boundary during the Cretaceous. The geologic setting was similar to today’s Andes Mountains, with subduction producing a volcanic arc that stretched along the continent’s southern coast. With the onset of the India collision, arc volcanism shut off. Later uplift of the Lhasa Terrane resulted in extensive erosion that eventually exposed the granitic batholith roots that had cooled beneath the ancient volcanoes. Around Drepung, many of these granite outcrops host colorful paintings of the Buddha.

The 17th-century hilltop Potala Palace is an architectural marvel and Tibet’s iconic symbol. Although Songtsen Gampo built his palace atop the same hill in the seventh century, when his Yarlung Empire fell 250 years later, the center of Tibetan Buddhism shifted first to Sakya and later to Shigatse, leaving Lhasa a quiet backwater. Things changed again when the fifth Dalai Lama vanquished the kingdom of Shigatse in 1642 and reestablished Lhasa as Tibet’s capital. The Dalai Lama built his palace, Potala, on Red Hill atop the ruins of Songtsen Gampo’s original structure.

Pilgrims from across Tibet visit Lhasa to circumambulate the Jokhang. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

The current palace is 13 stories (117 meters) tall and — thanks to its hilltop location — rises 300 meters above the valley floor to dominate its surroundings. With whitewashed stone walls, 5 meters thick at their base, plus more than 1,000 rooms and 10,000 shrines, Potala is massive by any measure.

This palace served as the winter home for the fifth through 14th Dalai Lamas (Norbulingka, another Lhasa attraction, served as their summer palace). The current (14th) Dalai Lama lived there until 1959, when he fled into exile in India during a Tibetan uprising nine years after China seized Tibet. The palace sustained minor damage during that uprising, but unlike most Tibetan monasteries, it escaped serious damage, reportedly because of the direct intervention of the Chinese Premier. Potala, along with Jokhang and Norbulingka, has been inscribed on the World Heritage list.

There’s a cap on the number of daily Potala visitors, and you are required to keep moving throughout the tour so, unfortunately, you can’t linger to admire the palace’s many impressive sights. Room after room contains innumerable statues and murals depicting Buddhist bodhisattvas — people who are able to reach nirvana but delay doing so out of compassion for others — as well as arhats and Buddhist kings. Eight Dalai Lamas are buried within the palace in giant dome-shaped shrines called stupas sheathed in gold and precious jewels. The most magnificent of these belongs to the fifth Dalai Lama. Built of sandalwood in 1690, the 15-meter-tall shrine is decorated with 3,721 kilograms of gold and 20,000 jewels and hosts the thumb of Sakyamuni, the Supreme Buddha, as well as the Dalai Lama’s remains.

ass=““caption”>Most four-day excursions to Mount Everest start by visiting Shigatse, Tibet’s second city. The tours typically visit several sites en route, including beautiful Kamba La Pass, Yamdrok, Tibet’s largest freshwater lake and one of the plateau’s four sacred lakes, and an impressive monastery belonging to a different sect of Tibetan Buddhism.

The tour departs Lhasa heading for Shigatse on the modern highway to Gonggar Airport, which is located 65 kilometers south of Lhasa in the Yarlung River Valley. The headwaters of this river rise in western Tibet near Lake Manasarovar, another of the sacred lakes, before flowing eastward and paralleling the Himalayan Mountains for 1,200 kilometers across southern Tibet. Thanks to the valley’s comparatively low elevation and mild climate, most of Tibet’s population lives along the Yarlung, or one of its major tributaries, such as the Lhasa River.

a> A roadside stupa (shrine) perched below Noijin Kangsang, a 7,191-meter-tall peak on the road from Yamdrok Lake to Gyantse. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.[/caption]

The Yarlung River flows along the Yarlung Tsangpo Suture, the fault zone that forms the boundary between the Eurasian and Indian plates. The precollision histories of the rocks on either side of the suture are completely different from one another; the rocks of the Lhasa Terrane to the north are directly juxtaposed to the south with metamorphosed sedimentary rock scraped off the colliding Indian Plate.

From the airport highway, the route to Yamdrok Lake, on Road S307, heads upriver a short way before climbing precipitously up a series of steep switchbacks on the southern valley wall. En route to the 4,797-meter-high Kamba La Pass are several spectacular Yarlung Valley overlooks that you’ll likely share with hordes of selfie-posing tourists dressed as Tibetan shepherds and cuddling a freshly coiffed lamb or Tibetan mastiff dog, provided by local families who set up shop at each viewpoint, catering to tourists who pay them a few yuan for each photo op.

After cresting the pass, Road S307 descends to 4,441-meter-high Yamdrok Lake, a narrow, twisting body of sparkling turquoise water whose shape Tibetans liken to a huge scorpion. Over strong Tibetan objections, the Chinese constructed a hydropower plant here in 1997. The 60-meter-deep lake is nearly a closed system, with inflow from its tiny catchment area balanced by evaporation. This situation means that diversions of water from the lake to drive the turbines are likely to decrease the lake level, resulting in ecological damage. For Tibetans, there’s an equally significant spiritual concern. According to legend, Yamdrok is Tibet’s “life-power lake,” so if the water dries up, all Tibetans will die. The Chinese have explored maintaining the current lake level by adding water pumped 900 meters uphill from the Yarlung River. However, not only would that require more energy than the power plant produces, but it would also introduce silt-rich river water into the nearly sediment-free lake, jeopardizing the lake’s turquoise color and the health of its fish population.

On the trip from Yamdrok to Shigatse is the Palcho Monastery in Gyantse, a worthwhile stop. It belongs to the Sakya, or Red Hat, Sect of Tibetan Buddhism, whose practices and traditions differ from those of the Gelug Monasteries near Lhasa. Its kumbun, a multistory stupa into which are built 108 small chapels, is the largest in Tibet — it’s well worth paying the small additional fee to see the structure. After visiting a few chapels, climb to the top story for a magnificent view of photogenic Gyantse Dzong (fort), one of the best preserved in Tibet, which occupies a commanding position on a rocky promontory above the river valley. It was built in 1390 to guard the southern approach to the Yarlung Valley and Lhasa.

The highlight of Shigatse is a tour of the expansive Tashi Lunpo Monastery, the seat of the Panchen Lama, the Gelug Sect’s second-ranking lama. Founded in 1447 by the first Dalai Lama, Tashi Lunpo is one of the largest monasteries in Tibet. You can easily spend several pleasant hours wandering through the vast residential complexes, gawking at the 26.2-meter-tall “Future Buddha” statue and touring the funeral stupas for the fourth through 10th Panchen Lamas. The stupas were ransacked during the Cultural Revolution in the mid-1960s to mid-1970s, but the 10th Panchen Lama rebuilt them and reinterred what relics and remains the locals could recover. This project concluded just six days before the Panchen Lama died in 1989. His stupa was completed in 1993.

For geology and geography buffs, no trip to Tibet would be complete without visiting 8,848-meter-high Mount Everest, which the Tibetans call Chomolungma, or “Goddess Mother of Mountains.” The Tibetan side of the world’s most famous peak is even more striking, and much less visited by Westerners, than its southern flanks in Nepal.

Most tours approach Everest Base Camp, the headquarters for large spring and fall mountaineering campaigns, from Shigatse along the so-called Friendship Highway, which the Chinese built to link Tibet with Nepal. Along the way, our group stopped at Sakya Monastery, the seat of the Sakya Sect, whose Mongolian-inspired architecture varies from most other Tibetan monasteries. The buildings are also painted differently; instead of the typical solid red and white adornment, Sakya’s buildings are instead painted gray with vertical red and white stripes.

The road to Everest Base Camp leaves the Friendship Highway at the scruffy town of Tingri, which is set in a barren landscape of contorted schist. The schist consists of weakly metamorphosed sedimentary layers deposited on the Indian subcontinent’s northern edge. As India was thrust beneath the Lhasa Terrane, these sediments were first buried and metamorphosed, then scraped off the downgoing Indian Plate and became incorporated into the stack of thrust sheets that now make up the Himalayas.

When we visited in 1999, Tingri lay at the end of the pavement; it took hours to drive the last 85 kilometers, jostling the whole way, to the Rongbuk Monastery and Everest Base Camp. But, like almost everything in Tibet, that’s changed. Now, a 1.5-hour drive on a freshly paved highway, which climbs up and over a 4,500-meter-high pass with jaw-dropping panoramas of the Himalayas, delivers you to a tourist camp in the upper reaches of the Rongbuk Valley next to the monastery. The camp is a gaggle of shepherd’s yurts equipped with cook stoves and raised sleeping platforms loaded with wool blankets to keep visitors warm during the frigid nights. The lodging isn’t fancy, but the camp has a friendly, rural feel and is comfortable, considering the remote location at 5,000 meters elevation.

At first, you may be disappointed that the view of Mount Everest is commonly obscured by mist. But the mist is constantly on the move, so if you keep popping out of your yurt, there’s a good chance you’ll see the mountain appear for a few minutes before its slopes are once again cloaked. When you do see the mountain, its majesty is awe-inspiring. Because Everest rises directly above the Rongbuk Valley, unobscured by foothills, the view is even more dramatic than from the Nepalese side. The mountain is especially breathtaking at sunset, when its bulky pyramidal summit glows red-brown long after all the surrounding peaks have fallen into shadow.

Heading back to Lhasa from Mount Everest, you’ll retrace your route to Shigatse and stay there for a night, giving you the opportunity to wander the Old Town’s lively streets. From there it’s just a half-day’s drive back to Lhasa along the mighty Yarlung River, which has carved an impressive gorge along this route. Most tours stop just upstream of the gorge to visit a traditional Tibetan incense workshop, where you can observe the Rube Goldberg-like flumes and waterwheels the incense makers have designed to crush the sandalwood and other logs into the pulp they form into fragrant incense sticks. From there it’s a short trip back to Lhasa, which you’ll depart with your mind filled with memories of warm Tibetan hospitality and your camera brimming with images of stunning landscapes from your journey above and beyond the rest of the world.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.