by Terri Cook and Lon Abbott Tuesday, January 16, 2018

Mega-resorts along the Las Vegas Strip make a convenient base for exploring the area's spectacular scenery. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Known for its dazzling neon lights, mega-casinos with nonstop gambling, high-end shopping and restaurants, and marquee shows, Las Vegas is an unapologetic icon of American hedonism — and one of the country’s top tourist destinations. Our eagerness to visit Sin City, however, had nothing to do with spinning roulette wheels or the clanging slot machines that would quickly claim our $10 gambling quota. We flew to Las Vegas to see the spectacular scenery beyond the slots: southern Nevada’s craggy limestone peaks, colorful sandstone canyons and enormous conservation areas that, despite the searing desert heat, harbor a tremendous diversity of plants and wildlife. From soaring summits and graceful bighorn sheep to prehistoric petroglyphs, we couldn’t wait to experience all that this desert oasis has to offer.

Like Lady Luck in Las Vegas’ casinos, southern Nevada’s landscape is also distinguished by its dramatic ups and downs. This is due to the presence of an accordion-like series of narrow, north-south-trending mountain ranges separated by long, flat valleys. The bumpy topography, which 19th-century geologist Clarence Dutton once described as resembling an army of caterpillars crawling northward, is the hallmark of the Basin and Range Province, a physiographic region that stretches more than 800 kilometers between the Sierra Nevada and the Colorado Plateau.

Visitors will need a car to explore southern Nevada's craggy limestone peaks, colorful sandstone canyons and enormous conservation areas just outside Las Vegas. Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI.

“The Basin and Range is, geologically speaking, relatively young. Until about 30 million years ago, the modern province consisted of an extensive highland, called the Sevier Highlands, that was uplifted beginning about 200 million years ago and supported by compression associated with the subduction of the Farallon Plate beneath North America. The Sierra Nevada comprised that subduction zone’s volcanic arc, and the compressive event that raised the highlands is known as the Sevier Orogeny.

Subduction ended when the eastward-moving Farallon-Pacific plate spreading ridge met the subduction zone, which triggered major tectonic changes that led to the creation of California’s San Andreas Fault and stretched and thinned the crust beneath the Sevier Highlands. Robbed of their underlying support, the highlands collapsed under their own weight, cracking along a series of north-south-trending faults that dropped valleys down between parallel mountain ranges to create the Basin and Range.

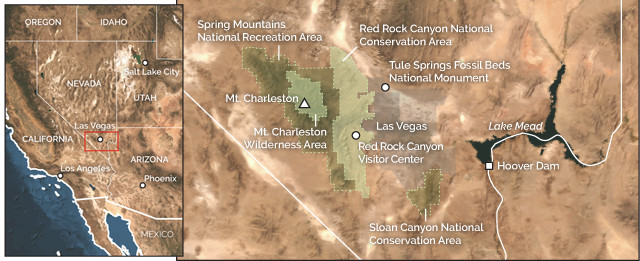

Sediments eroded from these ranges have since partially filled the intervening valleys, creating their smooth floors. Today, greater Las Vegas sprawls across the arid Las Vegas Valley, which is surrounded by steep ranges whose strong air drafts can sometimes make for bumpy flights into and out of the city. The most dramatic of these are the Spring Mountains, which abruptly rise more than 2,400 vertical meters from the city’s western edge and host several of Las Vegas’ top natural attractions.

A great place to explore Las Vegas’ backdrop is Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area, where a maze of deep, winding canyons is carved into dramatic red and white sandstone near the base of the Spring Mountains. With more than 2,000 rock climbing routes and two dozen trails ranging from casual strolls to challenging scrambles, Red Rock Canyon is one of the region’s most popular destinations off the Strip. Next to rock climbing, the best way to explore the conservation area is by driving or cycling the 21-kilometer-long scenic drive, which begins by the visitor center, and then hiking one or more of the beautiful trails that intersect it. The Calico Hills Trail offers up-close views of the beautiful Aztec Sandstone, a thick layer of Jurassic rock left behind by a Sahara-sized sand sea that stretched from here to modern-day Wyoming between about 190 million and 180 million years ago. The presence of “rusted” iron minerals in the red rock gives it the distinctive crimson color for which the area is named.

With abundant recreation opportunities and dramatic scenery, Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area is one of Las Vegas' most popular attractions. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

The steep, sweeping layers (crossbeds) visible in the canyon walls are the hallmark of deposition in desert sand dunes. Even after the sand was buried and cemented into rock, the crossbeds were so perfectly preserved that you can still tell which way the wind was blowing in this spot nearly 200 million years ago.

“Another worthwhile hike is the moderate, 3.6-kilometer round-trip route that leads from the White Rock parking area to the Keystone Thrust, a major fault active about 100 million years ago during the Sevier Orogeny that stacked much older limestone atop the colorful Aztec Sandstone. This limestone comprises the bulk of the Spring Mountains, which are named for their numerous life-giving springs, including the Willow and La Madre springs that emerge in Red Rock Canyon.

Although only a 45-minute drive from downtown Las Vegas, the Spring Mountains National Recreation Area is a world apart from the glitz of the city. In stark contrast to the prickly pear cacti and creosote bushes sprinkled across the dusty valley floor far below, tall stands of evergreen thrive in the cool, moist alpine environment, and snow lingers for months in the recreation area, which includes 3,632-meter Mount Charleston, the range’s highest peak.

The Spring Mountains are composed of a thick pile of limestone that accumulated in a westward-deepening sea between about 520 million and 280 million years ago. The fossilized remains of brachiopods, sponges, corals, crinoids, gastropods and other marine organisms are still visible in limestone outcrops throughout the Spring Mountains, including at the summit of Griffith Peak.

Near the end of the Paleozoic Era, as sea level dropped, seawater evaporating in intertidal areas left behind beds of gypsum that are still locally mined for use in drywall. During the Triassic, rivers piled sand and mud atop the limestone and gypsum. As the climate dried out during the Jurassic, sand dunes blew across the landscape. Those dunes were later buried by younger sediments, cementing the loose sand to form the Aztec Sandstone. Subduction that commenced along the North American West Coast during the Triassic, contemporaneous with the rivers that flowed across the Las Vegas landscape, eventually squeezed southern Nevada’s rocks and thrusted the older limestones up and over the Aztec Sandstone and other Mesozoic rocks along the Keystone and other thrust faults.

Mummy Spr'ng, which freezes during the cooler months, is one of the numerous life-giving springs that emerges from the thick pile of limestone that forms the Spring Mountains. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

“The Spring Mountains’ high elevation and encircling desert form a “sky island,” isolating plants and animals that have become biologically diverse. The recreation area hosts 25 species found nowhere else in the world, including more than a dozen plants and the Palmer’s chipmunk. In addition to providing vital habitat, the recreation area features a ski resort, campgrounds and an extensive trail system for hiking, biking and backpacking in summer and snowshoeing and cross-country skiing in winter.

In the heart of the Spring Mountains, the Mount Charleston Wilderness Area shelters large stands of gnarled bristlecone pine trees, including Raintree, the range’s oldest-known bristlecone, which has stood watch over Las Vegas Valley for 3,000 years. If you’re up for a challenge, you can hike to Raintree (and the nearby Mummy Spring) along a steep, 8.6-kilometer out-and-back section of the recreation area’s North Loop Trail. If you do visit, be careful not to compact or erode the soil near Raintree’s base, which could endanger this living treasure.

Another scenic spot where you can learn more about the region’s human and geologic history is the Sloan Canyon National Conservation Area on the city’s southeastern edge. This conservation area protects 300 panels of rock art that collectively comprise one of southern Nevada’s most important cultural sites.

Access to the largest rock art galle’y is via the 7-kilometer out-and-back Petroglyph Canyon Trail (BLM 100 Trail), which follows a sandy wash to Petroglyph Canyon, where intricate artwork up to 4,000 years old is visible on rocks along the lower canyon wall. The panels include intricate images of twisting snakes, clawed lizards, bighorn sheep and unidentifiable abstract symbols whose meanings have faded over time.

Although most of Sloan Canyon's petroglyphs are abstract symbols, some shapes are more familiar. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Hoover Dam is anchored in a dense layer of volcanic ash that erupted during Basin and Range extension about 13 million years ago. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

“The petroglyphs were chipped and scraped into varnished rock erupted from nearby volcanoes following the onset of Basin and Range extension. As this portion of the North American Plate thinned, the hot, underlying mantle rose to shallow depths. This decompression of the mantle rock triggered melting of magma, which wormed its way to the surface, where it erupted from dozens of volcanic centers scattered across the province.

“At Sloan Canyon, this volcanism occurred about 13 million years ago. The trail to Petroglyph Canyon leads through the core of one such volcano, Mount Sutor, which is made up of several sticky lava domes that eventually coalesced. Just before you reach the petroglyphs, you can see nearly vertical lineations formed by the viscous magma.

Another eruption that occurred east of Las Vegas at about the same time unleashed a dense cloud of ash so hot that it scorched the landscape. It also left behind a dense layer of welded ash more than 200 meters thick that today forms the walls of Black Canyon, the site of 221-meter-high Hoover Dam. This structure impounds Lake Mead, a crucial source of water for Las Vegas, Los Angeles and Phoenix.

Although it does not yet have any visitor infrastructure, the new Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument on the city’s northwestern fringe offers a window into much more recent events that have shaped the Las Vegas Valley. Designated in 2014, this monument preserves the remains of diverse ice age fauna that roamed the lush wetlands that covered this region periodically between about 100,000 and 12,500 years ago. The fossils include Columbian mammoths, dire wolves, several horse species, giant sloths, camels, and lions weighing up to 500 kilograms (more than double the weight of a large male lion today). In addition to mammal bones, the beds host the remains of several unusual plant species as well as ancient pollen, freshwater mollusks and dense concentrations of preserved cicada burrows.

Fossil-rich limestone beds just north of Las Vegas host the remains of giant sloths, camels, Columbian mammoths and other ice age fauna. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

“As the site is developed, future research and interpretation will help scientists and visitors understand why these animals became extinct in just a few hundred years, what roles climate change and human predation played, and how the loss of these fauna ultimately affected the Mojave Desert ecosystem. The monument also preserves part of historic Tule Springs, an important source of water for plants and animals living in the modern Mojave Desert.

Regardless of whether or not you’re a gambler, Las Vegas makes an interesting base for exploring the area. We enjoyed strolling down the Strip, the 7-kilometer-long, casino-lined stretch of South Las Vegas Boulevard between Sahara Avenue and Russell Road (where the iconic “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas” sign is located). It’s easy to explore the city via the monorail, city bus or a hop-on, hop-off tour that allows you to reboard sightseeing buses at 15 different stops.

Las Vegas' iconic welcome sign has marked the Strip's southern end since 1959. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

The Strip’s casinos try to outdo each other with kitschy activities. You can ride a gondola through the Venetian Hotel, drink in the views (and a pricey cocktail) atop the half-scale replica of the Eiffel Tower at the Paris Las Vegas Hotel, or zip through the Big Apple skyline aboard the loop roller coaster at the New York-New York Hotel. Time and budget permitting, you can also scare yourself silly on one of the thrill rides atop the Stratosphere Tower or shop ‘til you drop in the swank Caesars Palace or the pyramid-shaped Luxor Hotel. Geo-buffs might also want to wander by the Mirage Hotel, whose Las Vegas Boulevard frontage boasts a 16-meter-high volcano that erupts colorful fireballs at regularly scheduled intervals in sync with a custom soundtrack.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.