by Terri Cook and Lon Abbott Monday, February 29, 2016

The King's Highway offers travelers dramatic scenery and a chance to follow an ancient trade route used by many civilizations. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

The King’s Highway, a Middle Eastern thoroughfare that once stretched from Egypt to the Euphrates River, has been used by numerous civilizations over the last few thousand years. Since the Iron Age, this storied path has served as a vital trade route along the north-south spine of a narrow plateau cutting through the center of Jordan. A trip along the King’s Highway in Jordan today offers breathtaking scenery, world-class geologic features, surprisingly few tourists, and the chance to walk in the historic footsteps of people from Nabataean traders transporting frankincense to Petra, to descendants of Abraham traveling to the Promised Land, to Crusaders, Christian and Muslim pilgrims, and even Roman legions marching across the empire’s desert frontier. Each civilization has left its mark on this raw landscape, creating a cultural crossroads that offers an unforgettable journey through human and Earth history.

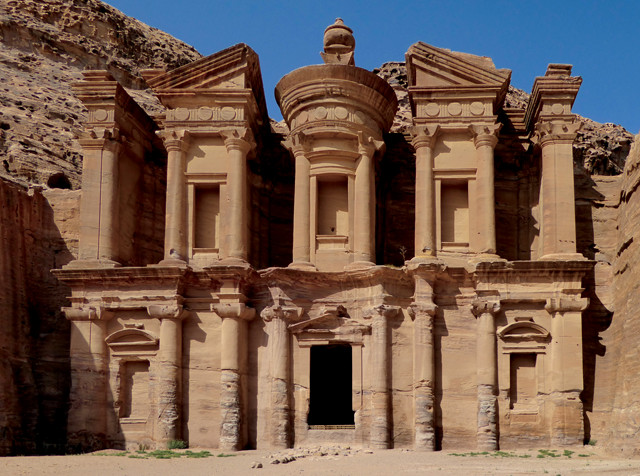

The carved façade of the Treasury is the best-known monument in the ancient Nabataean city of Petra. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

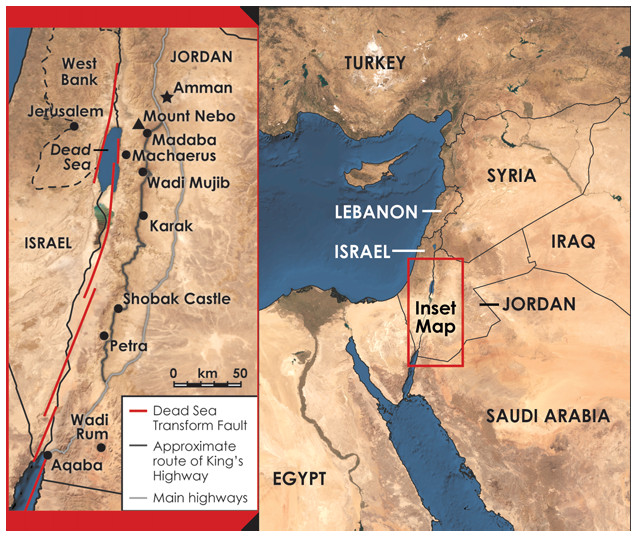

Officially known as the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, the country lies at a tectonic, as well as an historical, crossroads. The country’s western border lies along the Dead Sea Transform Fault, a strike-slip fault that connects the Red Sea Rift in the south to the collision zone that raised the Turkish mountains farther north. Jordan lies on the Arabian Plate, which over the last 20 million years has slid about 105 kilometers north and east relative to Israel on the Sinai Microplate across the Dead Sea Transform Fault.

Northeastward motion of the Arabian Plate along the north-oriented transform requires a component of extension in addition to strike-slip motion, creating a sort of mini-rift zone that geologists call a “pull-apart basin.” The Dead Sea, which at 429 meters below sea level is the lowest point on any continent, lies in this pull-apart basin, commonly called the Jordan (or Dead Sea) Rift Valley. Like all pull-apart basins and true rifts, the Jordan Rift Valley is bounded by normal faults, one side of which has been flexed upward to create adjacent highlands, known as the rift flank. The King’s Highway winds its way along the spine of this rift flank, which rises abruptly above the Jordan Valley to an elevation ranging from 700 to 1,200 meters — high enough to be dusted with snow in winter — and then slopes down gradually to the arid eastern desert.

The 280-kilometer-long King's Highway in Jordan runs along the upland spine flanking the Jordan Rift. Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI.

The rift flank exposes a stack of three distinctive rock units that are easily visible as you explore the King’s Highway from the capital of Amman to the coastal city of Aqaba. Jordan’s rocky foundation consists of Late Precambrian granitic and metamorphic rocks. These crystalline basement rocks are overlain by Cambrian sandstone of the Ram Group, which consists of debris deposited by northward-flowing braided rivers. (It is out of this beautiful red and tan rock that the Nabataeans, a nomadic Arab tribe, started carving the grand city of Petra in the fourth century B.C.) The Neo-Tethys Sea began to open north of Jordan in the Jurassic, causing the area to slowly subside. As the sea crept in, Early Cretaceous sandstone accumulated near the coastline, followed by a thick pile of shallow marine limestone and phosphorite throughout the remainder of the Cretaceous and into the Eocene. This phosphorite, which caps the central plateau, is the kingdom’s principal export.

Jordan's rocky foundation consists of Late Precambrian granitic and metamorphic rocks, like these hills seen just north of Aqaba. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

The 280-kilometer-long King’s Highway reportedly got its name from an alliance of four kings who marched their troops to battle along this path, an event mentioned in the Bible’s Book of Genesis. The Bible also names the “highway” as the route that Moses asked permission to cross after leading his people out of Egypt.

Madaba is known for its Byzantine mosaics, the most famous of which is a sixth-century map, believed to be the oldest surviving map of the Holy Land. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Today, the modern remains of the King’s Highway begin in Madaba, a small city 40 kilometers south of Amman known for its Byzantine mosaics. The most famous of these mosaics is an exquisite sixth- century example thought to be the oldest surviving map of the Holy Land. Housed in the 19th-century St. George’s Church, the masterpiece was discovered in the rubble of an older church destroyed by an earthquake in 747. The map depicts the major biblical sites between Palestine and Egypt. Although incomplete, it’s still possible to see delicate details like fish swimming in the Jordan River and Palestine’s city walls. Mount Nebo, from where Moses purportedly first saw the Holy Land, stands a few kilometers west of Madaba. It boasts a museum, a basilica with Roman mosaics, and sweeping views toward the Dead Sea, nestled in the Jordan Rift Valley far below.

From Madaba, the King’s Highway winds southward across the gently undulating central plateau. A half-hour’s drive south is the ruined hilltop fortress of Machaerus, the castle of Herod the Great, where, according to the Jewish historian Josephus, John the Baptist was beheaded in one of the caves near its base. Like the rest of the scenery along this part of the highway, this hilltop is composed of cream-colored limestone and phosphorite. Driving south, you approach the former shoreline of the ancient Tethys (which was oriented east-west), where the original depositional positions of different sedimentary layers are preserved. Thanks to the plateau’s alignment perpendicular to the ancient shoreline and the fact that there has been minimal tectonic disruption through the millennia, visitors today can envision how the sea gradually encroached onto the continental margin.

Wadi Mujib, the 600-meter-deep canyon known as the "Grand Canyon of Jordan," is carved through a thick cap of limestone and phosphorite deposted in a shallow sea. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Nowhere is the immense thickness of the hill’s limestone cap more breathtakingly evident than at Wadi Mujib, the 600-meter-deep canyon crossed by the King’s Highway between Machaerus and Karak. The steep, winding switchbacks here provide ample opportunity to see the phosphorite and limestone layers of the “Grand Canyon of Jordan.” A viewpoint on the canyon’s north side allows motorists to safely enjoy the view and glimpse, to the southeast, localized outpourings of young basalt associated with pull-apart basin extension. Limestone has been the region’s primary construction material through the ages. Karak Castle, built by Crusaders during the 12th century and retaken by the Muslim armies of Saladin a half-century later, and Shobak Castle are two impressive strongholds built of square limestone blocks.

As scattered ruins attest, legions of Roman soldiers once marched along the King's Highway across the empire's desert frontier. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Few places can rival the aura and grandeur of Petra, a city carved out of the relatively soft red Ram Sandstone between the fourth century B.C. and the second century A.D. The dramatic entrance to the ancient city is through the Siq, a towering slot canyon just 3 meters wide in places. The farther you walk along the cool, shady canyon, the higher the sandstone walls loom above you. Suddenly, the slot opens into a large wash, and Petra’s most elaborate ruin, the Treasury, soars above you.

Despite its name, which comes from the legend of an Egyptian pharaoh who purportedly hid treasure here, archaeologists discovered that the Treasury is a tomb built in the early first century A.D. for the Nabataean ruler, King Aretas III. The Treasury’s 43-meter-high façade is a prime example of sophisticated Nabataean craftsmanship: Greek and Egyptian influences are evident in the intricate details, from the half dozen columns at its base to the winged Victories and eroded eagles — said to carry away the souls of the deceased — near the top.

The dramatic entrance to Petra is through the Siq, a narrow slot canyon carved naturally through the relatively soft Ram Sandstone. Credit: both: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Thanks to their starring role in the film “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade,” the Siq and the Treasury are the best-known features at Petra, but more than 800 monuments await your exploration. Today, Petra, a World Heritage site, is accessed from the sprawling modern town of Wadi Musa, whose hotels and restaurants nudge right to the entrance gate, where visitors must pay a hefty $70 entrance fee. As no vehicles are allowed, your access choices from the gate are a delightful 15-minute walk or a horse or chariot ride down the ever-deepening Siq slot canyon. Only a handful of snack bars, curio shops and toilets exist within the 26,000-hectare site, so you’ll want to plan ahead. Nowadays, the crowds are surprisingly small for a world-class tourist site and the tall sandstone walls block most of the modern sights and sounds, so it is easy to immerse yourself in the Rose City’s prodigious ambiance.

Left: Despite its name, the Treasury was a tomb carved in the first century A.D. for the Nabataean ruler King Aretas III. Right: Colorful Liesegang rings adorn many of Petra's carved rock faces. Credit: both: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Between the quality of the stone and the skill of the Nabataean craftsmen, the site was destined for architectural grandeur. The Ram Sandstone is crisscrossed by a web of red, purple, black and ochre veins, known as Liesegang rings, whose color is produced by the variable enrichment and depletion of iron oxides precipitated from supersaturated groundwater that once flowed through the rock. The Liesegang rings swirl elegantly around every Nabataean pillar and alcove.

The view down to the Dead Sea Rift from the Monastery encompasses the unconformity between the dark basement rocks and the reddish Ram Sandstone. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

For a panoramic city overview, hike (or ride a donkey) up a narrow side canyon to the High Place of Sacrifice. Near the top, a series of steep steps leads up to an ancient altar. The hewn depressions here may have been used to collect water and to channel the blood of sacrificial animals. The views from the top are stunning, and the massive scale of the ancient city becomes evident. The sandstone walls surrounding Wadi Musa are creased by narrow gullies and slot canyons like the Siq and the side canyon used to reach the High Place of Sacrifice. Each valley, or wadi, is eroded along a joint, or planar crack, in the bedrock that channels rainfall during rare desert storms, causing erosion that widens and deepens them over time.

To get to the Monastery — a temple dedicated to a first century B.C. Nabataean king, and Petra's largest monument — visitors must hike up 800 stone steps.Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Another such joint leads from the city center to Petra’s other must-see attraction: the Monastery. The steep hike climbs 800 stone steps, but the view of Petra’s largest monument, with its 45- meter-high façade, is worth every sweaty step. Despite its name, the Monastery likely served as a temple dedicated to King Obodas I, who reigned in the first century B.C.

The High Place of Sacrifice offers a panoramic view over the ancient city of Petra, which sprawls along the banks of Wadi Musa. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

A short distance beyond is the so-called Grand Canyon Overlook, where you can sip refreshing Bedouin mint tea and take in panoramic views of the Monastery in one direction and the Jordan Rift escarpment in the other. Only the escarpment top consists of Petra’s red sandstone; the rest is composed of dark Precambrian volcanic rock. This volcanic rock erupted as lava 550 million years ago on the floor of an earlier pull-apart basin nearly identical to the modern one visible from the overlook. Trace the contact between the rock types laterally across the escarpment and you’ll see that the erosion surface isn’t flat; you can still trace the contours of 550-million-year-old hills that were slowly buried beneath the alluvial fans and river sands that make up the Ram Sandstone.

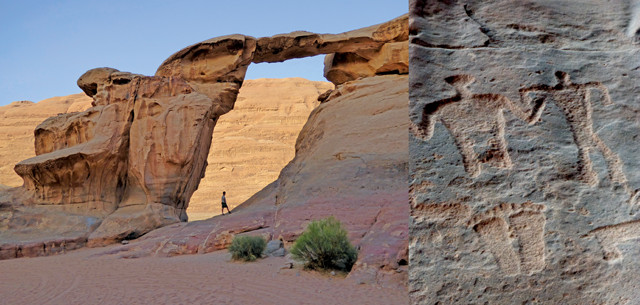

Wadi Rum is an otherworldly desert that has been used as a stand-in for Mars in multiple movies, including the recent blockbuster "The Martian"; it also inspired the writings of Thomas Edward Lawrence, better known as "Lawrence of Arabia." Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

From Petra, the King’s Highway descends to the valley of Wadi Rum, an otherworldly desert that has been used as a stand-in for Mars in multiple movies, including the recent blockbuster “The Martian.” The setting and the hardiness of the Bedouin who live in this extreme environment have inspired generations of people, most famously Thomas Edward Lawrence — also known as “Lawrence of Arabia” — a young English army officer who visited in 1917 while accompanying Arab troops revolting against the Ottoman Empire. His vivid descriptions in his autobiography, “Seven Pillars of Wisdom,” have immortalized the people and the scenery.

The Great Unconformity, the contact between the overlying Ram Sandstone and the underlying crystalline basement rock, is easy to spot in the walls of Wadi Rum. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Explore graceful rock arches and stunning cliffs of Ram Sandstone on a four-wheel-drive tour that winds through the area’s parched, sand-covered wadis. Tours start at Lawrence’s spring, one of many that issue from the contact between the permeable Ram Sandstone and the underlying, impermeable granitic basement rock. Other activity highlights include running down a red sand dune and admiring ancient petroglyphs carved in a slot canyon. Those in a hurry can get a taste for Wadi Rum’s grandeur in a whirlwind, three-hour tour, but we recommend spending more time if you can. The magnificent sunsets and the opportunity to gaze up at the Milky Way in the blackest of night skies are worth it. After a sumptuous Mediterranean feast you’ll bed down inside a comfortable Bedouin goat hair tent, then wake up to an equally beautiful sunrise enjoyed over a delicious breakfast, while surrounded by geologic largess.

Exploring Wadi Rum's rock arches, cliffs, wide-open deserts, sand dunes and slot canyons — some of which have Nabataean petroglyphs (right) — requires a four-wheel-drive tour. Credit: both: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

The exceptionally clear, warm water of the Gulf of Aqaba makes for spectacular snorkeling. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

A night or two off the grid at Wadi Rum is enough to make you not want to rush to return to civilization, but return you must, eventually. An hour’s drive from Wadi Rum through rift flank mountains composed of naked white granite intruded by crisscrossing black diabase dikes lands you in the coastal city of Aqaba, where you can connect with the rest of the world by land, air and sea. But be sure to save enough time for one more Jordanian superlative, a snorkel or dive along the kingdom’s compact, 26-kilometer-long stretch of Red Sea coastline in the Gulf of Aqaba. The gulf, like the Dead Sea, is a pull-apart basin whose floor lies below sea level. The exceptionally clear, warm gulf water results in luxuriant coral reefs accessible just meters off the beach, making the gulf one of the world’s best-known snorkeling and diving spots.

Sunset over Wadi Rum. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Jordan today sits, as it always has, at a crossroads of civilizations and in the shadow of momentous events — not all of them good. Regional turmoil has understandably dampened many tourists’ enthusiasm to travel here, which is a pity: They are missing the journey of a lifetime. Those who choose to venture here despite the headlines discover a peaceful land inhabited by hospitable people. Travelers along the King’s Highway can’t help but notice humans’ long history of engagement with this landscape, and, for those who like their geology raw and uncloaked, it’s hard to imagine a more fascinating landscape.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.