by Callan Bentley and Alan Pitts Monday, October 15, 2018

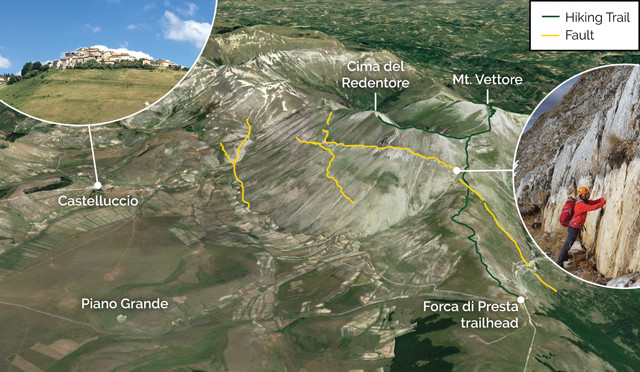

Monte Vettore, the highest peak in the Sibillini Mountains at 2,476 meters elevation, rises above the Piano Grande, or "Great Plain," at left. The summit is reachable by several hiking paths, the most popular of which traverses 5 kilometers from the roadside Forca di Presta trailhead (foreground) to the peak, crossing fault scarps formed in the past two years during large, damaging earthquakes. Credit: Alan Pitts.

The Apennine Mountains form the exposed, rocky backbone of Italy. In northwestern Italy, the mountains are linked to the Maritime Alps; from there, they wind sinuously southward in the form of several arcuate chains all the way to the southern terminus of the Italian Peninsula, where they disappear under the Gulf of Taranto before reappearing on Sicily as part of the Calabrian Arc. In the central Apennines, roughly three hours from Rome by car, Monti Sibillini National Park straddles the border between the regions of Umbria to the west and Marche to the east. The park offers exemplary views into the formation of Italy’s limestone spine, as well as several chilling lessons about the relationship between humans and the unstable land on which we live.

The landscape of the central Apennines is a manifestation of the geological processes that have acted on this region for more than 200 million years. It is a place where human history is closely tied to the terrain: a relationship that has produced terrific rewards of agriculture and art, as well as great catastrophes from earthquakes and landslides.

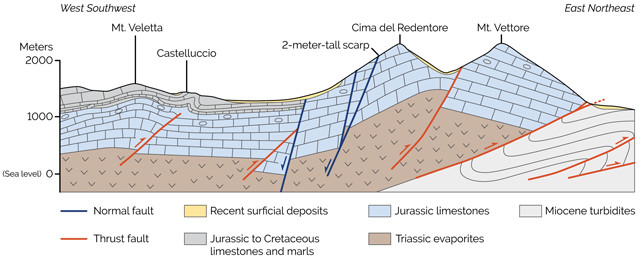

The Apennine Mountains run the length of the Italian Peninsula. In the central Apennines, Monti Sibillini National Park straddles the border between the regions of Umbria and Marche. Two main stages of Cenozoic tectonism shaped the Apennines: Compression along thrust faults during the upper Eocene and Oligocene that contorted and uplifted rocks in the western portion of the range, followed by extension along normal faults in the Pliocene and Quaternary that has created high flat basins surrounded by steep mountain topography. Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI, after Vezzani et al., GSA Special Paper, vol. 469, 2010.

The Sibillini Mountains, with their high pristine peaks and occasionally intense shaking, have for centuries evoked a sense of enchantment, both benevolent and sinister, in the minds of locals and visitors alike. The rugged terrain was named after a legendary medieval oracle, a sibyl, who, like the prophets of classical Greece, had the power to see the future and the past. Stories tell of a particular oracle who lived in this part of the Apennines, surrounded by treasures, in an underground paradise that could be accessed only through a high cave entrance at the top of Monte Sibilla, one of the highest peaks in the range. As the legend goes, quite a few European explorers ventured in search of the cave, and many never returned.

The story of the rocks of Monti Sibillini National Park begins in the Late Triassic with the opening of the Tethys Ocean between the supercontinents of Gondwana and Laurasia. In the Early Jurassic, warm and shallow Tethys waters along a passive continental margin in the vicinity of modern Italy created conditions ripe for the deposition of ample calcareous sediments, which piled up into a thick carbonate platform — an environment closely resembling the present-day Bahamas. Over time, the calcite shells of deceased organisms — particularly microscopic foraminifera — contributed more and more to these sediments, and thus to the eventual limestones that formed from them.

A geological cross section through the central Apennines in the vicinity of Monte Vettore and the Piano Grande. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI, after Pierantoni et al., Italian Journal of Geosciences, vol. 132, 2013.

The Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi, about 40 kilometers west of Monti Sibillini National Park, has a distinctive pink color because it was built from the Scaglia Rossa limestone. Credit: Callan Bentley.

A closeup of the Scaglia Rossa limestone the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi was built from. Credit: Callan Bentley.

The Italian naming convention for many of these limestones is straightforward. The Calcare Massiccio, for example, translates to “massive limestone.” The “scaglia” units are named for the “scaly” or flaky way that they weather, along with their color. The Scaglia Bianca is white, the Scaglia Rossa is red, and the Scaglia Variegata is mixed in color. Once you learn this naming code, you’ll recognize these limestones where they have been used in constructing buildings and towns of the central Apennines. For instance, the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi has a distinctive pink color because it was built from the Scaglia Rossa.

Within the Scaglia Rossa is the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary dating to 66 million years ago. The sudden drop in the diversity, size and ornamentation of foraminifera at the boundary tells of a cataclysmic global event that happened at the time: the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. At Bottaccione Gorge near Gubbio, about 60 kilometers northwest of the national park, the famous outcrop where scientists identified an iridium anomaly in the rock — which was later linked to the massive Chicxulub impact implicated in the mass extinction — remains a pilgrimage site for geologists.

Ascending a switchback into the Fiastrone River Valley, a 100-meter-tall outcrop of contorted rock displays striking zigzags, called chevron folds, in the thin layers of the Scaglia Rossa. The folds resulted from compression during the Miocene, which shoved the limestone layers over other rocks. Credit: Alan Pitts.

Amid the Lame Rosse, hoodoos rise from eroded Holocene sandstones and conglomerates. Credit: Isabella Vitali, public domain.

Two main stages of Cenozoic tectonism shaped the Apennines, partly overlapping in space and time. Beginning roughly 35 million years ago in the upper Eocene and continuing into the Oligocene, the older limestones in the western portion of the Apennines were compressed and contorted into folds and uplifted above the surrounding topography along thrust faults. As this compressional belt propagated eastward, arriving in the interior portion of the chain during the Miocene, thrust faulting generated deep marine sedimentary basins that became the repository for sediment that cascaded down along the ancient seafloor as turbidity currents, forming thick packages of sandstone and shale. These Miocene turbidites are syntectonic, meaning they formed at the same time that the compressional stresses were deforming the limestones.

The eastern portion of the Apennine chain, where this compressional activity is still occurring, is called the outer compressional belt, a naming convention likely due to the fact that Italian geology tends to be viewed from the perspective of Rome (which lies west of the mountains). The area around Lago di Fiastra, a reservoir in the far north of Monti Sibillini National Park, is a great place to examine the tectonic structures produced during the main compressive phase of Apennine mountain building, such as wonderful examples of folding and thrust faulting on both large and small scales.

Closer to Rome is an extensional belt on the western flank of the chain, where the Apennines are being stretched. In this zone, Pliocene- to Quaternary-aged normal faults dissect the previously uplifted landscape, creating basins in the mountains that make for high flat plains surrounded by steep topography. Active movement on these faults continues today, sometimes with catastrophic results. Every time a fresh earthquake creates offset along these faults, it increases the local relief. Some rocks rise higher into the sky, while others sink lower. This encourages the breakdown of the mountains and the filling of the basins. The Piano Grande (“Great Plain”) of the Castelluccio Basin is a unique location to see the evidence of these active mountain-sculpting processes, such as ground surface ruptures along the trace of long extensional faults and the vast, flat intermontane plain.

Lago di Fiastra, nestled amid the peaks in the northern part of Monti Sibillini National Park, is a reservoir formed by the impoundment of the Fiastrone River. Credit: Alan Pitts.

Approaching the northern part of Monti Sibillini National Park from the northeast, you’ll climb Strada Provinciale (“provincial road” or SP) 91 into the mountains. Ascending a switchback into the Fiastrone River Valley, a prominent 100-meter-tall contorted rock will catch your attention. The striking zigzags in this rock are chevron folds in the thin limestone layers of the Scaglia Rossa. The strata date to the early Late Cretaceous, roughly 100 million years ago, but the folding that overprints them only occurred in the Miocene, about 15 million years ago or less. This is a fine place to contemplate the first stage in the tectonic evolution of the Apennines, when compressional stresses shoved older rocks atop the Miocene turbidites. Also visible here, if you gaze across the valley, are several thrust faults and recumbent anticlines, as well as the tracks of recent debris flows and small landslides.

Lago di Fiastra's emerald green to blue waters and the abundance of activities for visitors make the area a popular summertime retreat for locals. Credit: Alan Pitts.

If you’re interested in stratigraphy, you’ll want to check out the Bonarelli Level, a 3-meter-thick interval of organic-rich black shales within the Scaglia Bianca. A dark sliver of rock within a stack of white limestone thousands of meters thick, the Bonarelli Level is a key marker-bed for geologists amid the contorted structure of the region, sliced and diced as it is. The level marks the stratigraphic boundary 93.9 million years ago between the Cenomanian and Turonian ages of the Cretaceous. It can be seen in many locations throughout the Apennines and Alps, although it’s an expression of a global-scale oceanic anoxic event — a time when oxygen levels in the oceans dropped, allowing undecayed organic matter to build up on the seafloor. The cause of the ocean anoxia — whether tectonic or climatic in origin — is still disputed. The best place to view the Bonarelli Level in this area is from the roadside, about 10 kilometers down the road from the chevron folds viewpoint.

Tectonic extension along normal faults that bound the Piano Grande on its eastern edge continues to drop the floor of the basin, and the town of Castelluccio, downward with respect to the mountains to the east, including Monte Vettore. Hiking along the trail that ascends to Vettore's summit from the Forca di Presta trailhead takes you across fault scarps created during recent earthquakes, including a particularly impressive 2-meter-tall scarp. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI, based on an image from EMERGEO working group.

Nearby, the sediments and formations of the Lame Rosse (“Red Blades”) badlands are another spectacular site. Looking more like southern Utah than central Italy, it’s a site that will impress even nongeologists. Here, towering hoodoos rise from extremely young (Holocene) sandstones and conglomerates — most tinted varying shades of orange — that don’t neatly fit into the overall story of the formation of the Apennines, but rather represent periods of intense erosion of previously unvegetated rocky slopes. A scenic hiking trail from the Lago di Fiastra Dam will take you to the outcrops.

A gem of this part of Monti Sibillini National Park, Lago di Fiastra is a reservoir on the impounded Fiume Fiastrone (Fiastrone River) with milky, emerald green to blue waters that is a classic summertime retreat for locals. In addition to plenty of hiking and biking (both road and mountain), the village of San Lorenzo on the eastern shore of the lake hosts several tourist facilities offering opportunities to boat, paddleboard, kayak, swim or just lounge on the beach with a gelato or drink in hand. After the recent earthquake sequence that hit the region in 2016 and 2017, officials lowered the reservoir level to reduce the risk of a landslide-induced tsunami overtopping the dam. The low water levels can make for a steep descent to the beach, which adds to the surreal beauty of the location.

The Piano Grande is a high plain about 1,200 meters above sea level and surrounded by the highest peaks in the central portion of Monti Sibillini National Park. Credit: Alan Pitts.

Downstream of the reservoir, the Fiastrone River scours through the Scaglia Rossa limestone, revealing several older stratigraphic units of the Apennines. Visitors can wade through the river in the Gole del Fiastrone (Fiastrone Gorge) in an experience reminiscent of the Narrows in Zion National Park or Arizona’s Antelope Canyon. However, thanks to the buffering of water flow provided by the dam at the northeast end of the lake, there is little risk of being swept away in a flash flood.

In late summer, a vibrant mosaic of colors arises from the lentil fields in the Piano Grande in a spectacle known as the Fioritura, or "flowering," of Castelluccio. Credit: Stefano Avolio, CC BY-SA 2.0.

About 25 kilometers south of Lago di Fiastra, the Piano Grande is a high plain sitting about 1,200 meters above sea level and surrounded by the highest peaks in the central portion of the national park. Guarding the Piano Grande from above is the village of Castelluccio, the highest in the region and formerly home to some 130 people who have since been relocated to newly built anti-seismic structures until the town is reconstructed. This location is famous for producing lentils and distinctively cured salamis.

The village of Castelluccio, perched atop a hill overlooking the Piano Grande, was heavily damaged during a magnitude-6.6 earthquake that occurred in October 2016 along a normal fault roughly 10 kilometers northwest of the town. Credit: Alan Pitts.

Lago di Pilato, a natural high-elevation lake, sits at 1,941 meters elevation in the trough of a glacially carved valley between Monte Vettore and another peak, Cima del Redentore. Swimming is prohibited in the lake as it hosts a rare species of freshwater crustacean. Credit: Shutterstock.com/Stefano Buttafoco.

Even higher above the Piano Grande sits Monte Vettore, which tops out at 2,476 meters. This summit is reachable by several hiking paths of varying difficulty, the most popular of which starts at the Forca di Presta trailhead off SP477 and traverses 5 kilometers to the peak. The trail crosses new fault scarps formed in the past two years during large, damaging earthquakes. Hikers looking to extend their trek for a more challenging climb can continue on the trail to see the crystal blue waters of the Lago di Pilato, one of the few natural lakes in the region. This lake, which sits at 1,941 meters elevation, rests in the trough of a broad, glacially carved valley, one of the most notable glacially derived landscapes on display in the Sibillini Mountains. Though the water may seem inviting after a long hike up the mountain, swimming is strictly prohibited, as Lago di Pilato hosts a rare species of freshwater crustacean that is found only in this tiny mountain lake.

Hiking, mountain biking and horseback riding are popular activities for tourists in the Piano Grande. In late summer, the area hosts a vibrant mosaic of colors that burst from the lentil fields, a spectacle known as the Fioritura, or “flowering,” of Castelluccio that attracts visitors from all over Italy. The rich cultural and culinary traditions (see sidebar) born in this region are at risk of being lost, however. Due to heavy damage from the recent earthquakes, several of the towns and commercial enterprises, once thriving, are now struggling to remain active.

Many towns in the central Apennines were damaged during the 2016–2017 seismic sequence that hit the region. Here, rubble from a toppled building remains along a roadside in the town of Visso. Credit: Callan Bentley.

Aside from being one of the most picturesque locations in Monti Sibillini National Park, and a treasured recreational location, the Piano Grande is also an active extensional basin. The natural beauty of this landscape derives from a system of normal faults that bound the basin on its eastern edge and drop the floor of the Piano Grande downward with respect to Monte Vettore. But motion on faults in this region can have severe consequences. In October 2016, the magnitude-6.6 Norcia earthquake struck near here, damaging many nearby towns, including Castelluccio. Stone buildings partially collapsed and much of the town was reduced to rubble.

A large landslide triggered by the October 2016 Norcia earthquake dammed the Nera River in the western part of the park and closed state highway 209 for almost a year. Credit: Callan Bentley.

Gleaming white limestone, freshly exposed by the landslide, can be seen high above the road. Credit: Callan Bentley.

That quake was just one in a string of earthquakes that struck central Italy in 2016 and 2017. This seismic sequence consisted of three large shocks each greater than magnitude 6.0, along with thousands of aftershocks, occurring between August 2016 and January 2017 along the central Apennine fault system. To this day, the central portion of Castelluccio is closed to traffic, with only residents allowed into the “red zone” for short periods of time. The towns of Amatrice, Caldarola, Camerino, Ussita, Visso and many others also sustained substantial damage and now have similar exclusion zones where access is limited.

The drive from Preci to Visso along the Strada Statale (“state highway” or SS) 209 (local signage denotes this area as “Valnerina”) in the western part of the park takes you through part of the Nera River Valley, offering views of a large landslide triggered by the Norcia earthquake; the slide dammed the Nera River and closed this road for almost a year. Meanwhile, high above, freshly exposed limestone gleams white and a frighteningly large amount of rubble can be seen on both sides of the river on the valley floor.

Though these earthquakes are destructive in the short term, they are also responsible for sculpting the landscape of the central Apennines. The mythological sibyls had the power to see into the future and the past, and the same could be said for geological travelers to this special place: The past is revealed in outcrops and landscapes that tell a story of sedimentary deposition, compressional mountain building and tectonic extension.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.