by Robert and Johanna Titus Monday, June 8, 2015

Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI.

The dramatic easternmost edge of upstate New York’s Catskill Mountains goes by several names. The Algonquin called it the Wall of Manitou — Manitou being the “Great Spirit.” Geologists frequently call it the Catskill Front. Perhaps the most descriptive term for it is the Catskill Escarpment, as the range rises abruptly, and steeply, from the floor of the Hudson River Valley below.

The landscape has featured prominently in the work of famed American writers like James Fenimore Cooper and Washington Irving, and was the subject of many of the pioneering paintings from artists in the Hudson River School. It witnessed the birth of the American resort industry, with visitors drawn by natural scenery perhaps unmatched by anything east of the Rockies. And, most importantly, it features an amazing array of geology.

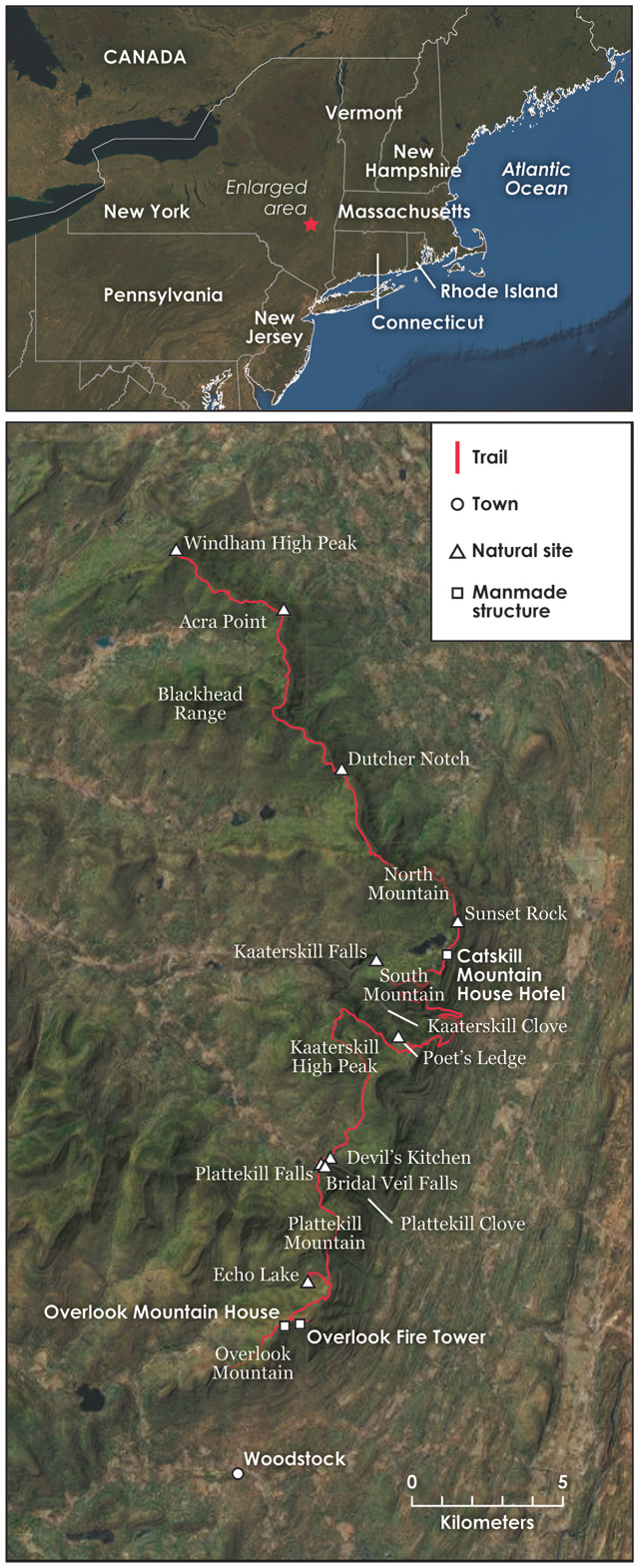

Recently, we ventured to the Catskill Front to hike part of the “Escarpment Trail,” which is composed of portions of several well-marked trails. Our three-day, point-to-point hike took us through Catskill Park, a vast New York state nature preserve set aside in 1894 and divvied into a number of separate forest preserves. Always to the east was the vast expanse of the Hudson Valley; always to the west were the Catskill Mountains. The trip can be completed hiking 15 to 20 kilometers a day, or about 6 to 8 hours per day depending on your speed, and camping each night (see sidebar). Anyone of average fitness could hike any portion of this itinerary, or could go a lot farther on the numerous trails throughout the region. The more geological knowledge you have, the more you’ll be able to envision this region’s former landscapes — filled with glaciers and torrents of meltwater. Everyone, however, can enjoy the grandeur that remains.

We began our trek at the Meads Mountain Trailhead at the base of Overlook Mountain, above the famed town of Woodstock, N.Y. We set out on the Overlook Trail, which initially took us on a climb through about 500 vertical meters of sedimentary rock, including sandstone ledges that alternated with horizons of red shale.

The sandstones in this area commonly display trough cross bedding as they were formed from river deposits in the Devonian Catskill Delta about 380 million years ago. The red shale strata, rich in iron oxides, are overbank deposits from the same unit. The Catskill Delta accumulated along the western base of the Acadian Mountains off to the east in New England during the Acadian Orogeny. As those mountains loomed higher on the horizon, they shed coarser sediments, which now make up conglomerates — called puddingstones locally — that become common high up on Overlook Mountain.

At the top of Overlook Mountain are the remnants of the historic tourist trade in the eastern Catskills: the ruins of the third incarnation of the Overlook Mountain House, which would have, no doubt, been a grand hotel had it not been beset by accessibility issues and poor timing. With the stock market crash and Great Depression, it never fully opened; by 1940, it had been boarded up and abandoned.

Continuing on the trail, we reached the old Overlook Fire Tower — built in 1927 and re-erected in its current location in 1950 — where we got our first glimpse of the region’s glacial past. During the Pleistocene, the Laurentide ice sheet overtopped the nearly 1,000-meter-high summit of Overlook Mountain, leaving evidence of its presence behind, such as polished, river-deposited sandstones and striations in other rock.

The fire tower offers views of the impressive edge of the Wall of Manitou. This portion of the escarpment comprises a 15-kilometer-long, straight-as-an-arrow wall of rock, with all of the Hudson Valley spread out below. The valley itself was carved largely by the ice sheet as it plucked loose masses of bedrock along southwest-trending joints, thus leaving the wall, which also trends southwest, behind.

After admiring the breathtaking vista, we returned to the main Overlook Trail and started descending Overlook Mountain. After about 2.5 kilometers, we veered left onto a side trail marked with yellow blazes. In Catskill Park, yellow trails always take hikers on interesting side trips, and this one was no exception: It took us down a steep slope to the bottom of a glacial cirque, where we came upon a tarn known as Echo Lake. A quick clap and shout will tell you how this quaint lake — a popular site for campers — was named.

Echo Lake is a remnant of the last phase of the ice age in this location, when all around us was an alpine landscape. Stretching off to the southwest of the lake is the Saw Kill Valley, carved by the Echo Lake glacier roughly 15,000 years ago.

Climbing back uphill to the main trail, we continued north to the eastern side of Plattekill Mountain, where we saw another chapter of local history — a sequence of long-abandoned bluestone quarries. Bluestone was the name given to the Devonian river sandstones — or feldspathic graywackes to be precise — in the area that could be split into fine, flat slabs and were bluish-gray in color. The durable stone was used throughout eastern North America, mostly to make sidewalks, but also as architectural and decorative stone. One site we observed had not only been a quarry, but had also hosted a village of stone huts for the mineworkers, mostly Irish immigrants. This whole region was once thick with such quarries, but the industry faded during the early 20th century and then migrated westward, leaving abandoned huts and heaps of slag rock behind. Almost all is green here now, as nature has slowly obscured the damage from the quarrying.

Toward the end of our first day of hiking, we entered an area known as Plattekill Clove (often called just Platte Clove). Plattekill Clove is one of two major canyons cut into the Wall of Manitou by glacial meltwater streams. Here, the trail crosses numerous low sandstone exposures, which, like those atop Overlook Mountain, were long ago beveled and striated by a glacier. Based on the compass directions of the striations at the various exposures, we could tell that the glacier here, pushed by the main mass of ice advancing down Hudson Valley, had ascended Plattekill Clove before veering south. Thus, as we descended into the Clove on our northward journey, we imagined ourselves walking into the face of the once-oncoming ice.

The glacier is gone of course, but Plattekill Clove is still home to Plattekill Creek, which flows over at least 17 named waterfalls on its way southeast toward the Hudson River. Transiting hikers and other visitors to the area can take a quick detour along a side trail to view a few of these falls, such as the picturesque, 20-meter-tall Plattekill Falls, followed by the 27-meter-tall Bridal Veil Falls. A little farther down the path, a bridge crosses a dramatic, nearly vertical gorge cut against the grain of the clove, the product of erosion along another southwest-trending joint. Known as the Devil’s Kitchen, the gorge is popular among experienced rock and ice climbers, but can be treacherous for casual hikers without rope and harness. (Note that this trail is not on state land, but rather is on land owned by the Catskill Center for Conservation and Development, which has its own rules for visitors.)

After camping overnight in Plattekill Clove, we resumed our journey north, climbing again. Following the forested Long Path trail for several kilometers, we traced the Catskill Front, heading for Kaaterskill Clove, the larger twin of Plattekill.

After skirting around 1,114-meter-tall Kaaterskill High Peak — a popular destination in its own right — to the west, we headed downhill again before bending back to parallel Kaaterskill Clove. Glimpses of the clove appeared off to our left through the trees, but we soon encountered another short yellow side trail that would take us to a scenic gem. Called “Poet’s Ledge,” it offers a sweeping view of all of Kaaterskill Clove — a magnificent panorama. Anyone would find it breathtaking, but to a geologist with a good imagination, a glance from this ledge will conjure images of a rising glacier filling the canyon, perhaps followed by another picture of the area glutted with torrents of erosive meltwater.

The Catskills tourism industry was born in this scenic canyon and flourished throughout the 19th century. Here too, the artists of the Hudson River School first began painting, helping stoke the mystique of the American Wilderness.

Next up was one of the most famous locations in all of the Catskills: Kaaterskill Falls.

A geologist’s first observation here might be of the prominent outcrops of Devonian sandstone over which Kaaterskill Falls drop about 70 meters in two tiers. But the site is also renowned as the birthplace of the Hudson River School of art. Here, in the autumn of 1825, a young artist named Thomas Cole produced sketches that would help initiate a new form of landscape painting. Whereas landscape artists in Europe had long painted domesticated, park-like scenes, Cole’s paintings captured remarkably raw views of nature as it was before human influence. This special sort of landscape art would come to be called the “picturesque.”

Cole’s canvases sold quickly and his career blossomed. Over the course of the next half century, scores of other artists joined him in portraying the virgin landscapes of the Catskills and, eventually, the whole of North America. The Hudson River School became America’s first significant artistic tradition and the paintings are still revered by many, particularly locals. As our hike continued, we passed many other sites captured on canvas by practitioners of the Hudson River School, and we felt the presence of artists such as Frederic Church, Harriet Cany Peale and Sanford Robinson Gifford.

Following the Escarpment Trail from Kaaterskill Falls took us along the northern rim of Kaaterskill Clove within North-South Lake Campground. We were hiking in the direction from which the Kaaterskill Clove glacier came, passing various scenic overlooks like Inspiration Point and Boulder Rock, which were created when the glacier plucked cliffs out of the ledges of sandstone.

Traversing across South Mountain, the trail took us toward the site of the former Catskill Mountain House Hotel, possibly the single-most historic location in the Catskills. This was one of America’s first resort hotels and, for most of a century, America’s finest one. The hotel first opened in 1824 atop a plateau on the flank of South Mountain. A “who’s who” of famous Americans stayed here: writers, artists, poets, actors, politicians, industrialists — you name it. The house eventually fell into disrepair and was razed by the state in 1963, which remains controversial to this day. But the site, with its famed 110-kilometer view over the Hudson Valley, remains. Beyond are the Taconic Mountains. Looking down into the valley, it’s not difficult to imagine it filled with the ice of the Hudson Valley glacier; look again, and see the distant waters of Glacial Lake Albany.

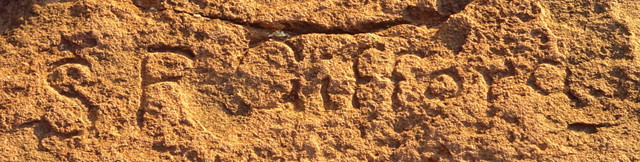

Hudson River School painter Sanford Robinson Gifford left his mark on the art world, and on the land itself, carving his initials into stone near South Lake. Credit: Public Domain.

Behind the hotel lay the twin North and South lakes. Each basin was scoured out when the Hudson Valley glacier rose up and swept into the Catskills — bedrock exposures along the lake shores again bear west-trending striations in abundance as proof. As the lakes also host the Catskills’ most popular campground, it was a fitting locale for us to spend the night after our second day.

On day three, we pressed north along the Escarpment Trail, soon entering what might be called the land of Rip Van Winkle. Anyone familiar with Washington Irving’s story will likely feel that this could be the very location where Rip met Hendrick Hudson’s crew and drank too much before falling asleep for 20 years. In fact, Irving had not yet actually come to the Catskills when he wrote the story. Nonetheless, this just seems to be the place! There is a flat glaciated platform where Hudson’s crew might have bowled, and an overhanging ledge of conglomerate where Rip might have spent a comfortable couple of decades sleeping.

In fact, we passed several more picturesque ledges carved by the glacier. Yet another yellow trail about a kilometer north of North Lake led to what is arguably the most scenic panorama in all of eastern North America: Sunset Rock. From this point, you can survey the lakes, all 12 square kilometers once owned by the Mountain House Hotel, and beyond, you can still make out part of Kaaterskill Clove. There is another sweeping view of the Hudson Valley, and off in the distance to the south are the Shawangunk Mountains. It’s no wonder Sunset Rock has long been a favorite Catskills spot for artists. Returning to the main trail, we ascended to the top of North Mountain, where we stood on the rim of a glacial cirque.

Roughly another 5 kilometers north, we found ourselves descending to the bottom of another gap in the Wall of Manitou, this one known as Dutcher Notch. Dutcher Notch, a former glacial spillway, was carved out of the escarpment by powerful meltwater currents.

Reaching Acra Point, we were in the home stretch of our trek. To our west, the upper reaches of Batavia Kill flow through a U-shaped valley that also was filled with a glacier near the end of the last ice age. Back to the south, the Blackhead Range rises, including a 1,200-meter beauty appropriately named Thomas Cole Mountain. Our final summit on this journey was Windham High Peak, where we took in our last grand vista, this one showing much of the upper Hudson Valley. Descending to a trailhead where State Route 23 passes below the mountain, we had reached the end of our excursion through a land gifted with breathtaking geologic, historic and artistic history.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.