by Amy Hogue Thursday, November 16, 2017

A quintessential view of the Gaspé Peninsula in eastern Quebec. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/krblokhin.

The geological and paleontological riches of Quebec’s Gaspé Peninsula have been known since 1844, when it was first explored by Sir William Edmond Logan, who is often called the father of Canadian geology. Since then, it has become a location of interest for both amateur and professional geologists looking to explore pristine rock formations and an abundance of fossils.

Located in eastern Quebec, the Gaspé Peninsula covers more than 30,000 square kilometers and is bordered by the St. Lawrence River to the north and Chaleur Bay to the south. The peninsula is divided into five regions — (clockwise from the northwest) the Coast, Haute-Gaspésie, Land’s End, Chaleur Bay and the Valley — with each offering its own points of geologic interest. A trip to the Gaspé is best completed by traveling around the peninsula on Route 132, a scenic highway that snakes its way through low-lying coastal regions, coastal escarpments, mountainous areas and the many small fishing villages scattered along the rugged coastline, where the brightly colored homes contrast with deep blue waterways.

The Gaspé Peninsula covers more than 30,000 square kilometers and is bordered by the St. Lawrence River to the north and Chaleur Bay to the south. It's divided into five regions, best explored by driving around the peninsula on Route 132. Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI.

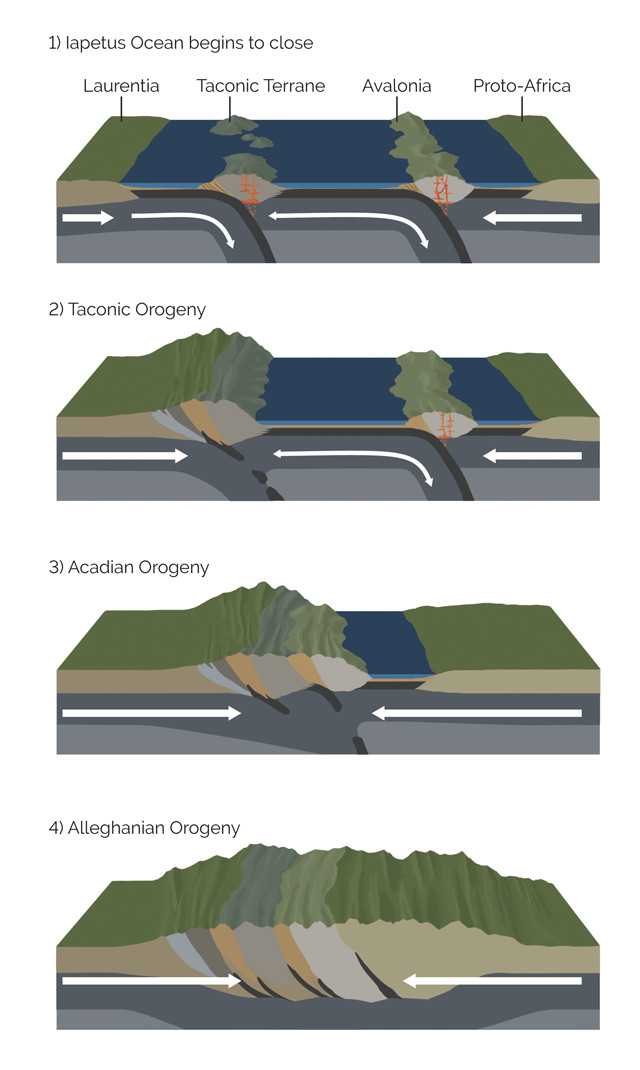

The mountains of the Gaspé are the Quebecois extension of the Appalachians, which formed over hundreds of millions of years as a result of three separate orogenies: the Taconic (480 million to 440 million years ago), the Acadian (415 million to 350 million years ago), and the Alleghanian (325 million to 260 million years ago). Together, these episodes led to the assembly of the supercontinent Pangea. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

The geologic story of the Gaspé Peninsula encompasses everything from the formation of the Appalachian Mountains, which stretch from Alabama to Newfoundland (and on into Scotland and Norway) — running right through the Gaspé — to the final closure of the Iapetus Ocean that existed from the Neoproterozoic into the Paleozoic, to the Pleistocene glaciation opening up the St. Lawrence River. The Appalachians were built over hundreds of millions of years as a result of three separate mountain-forming events, or orogenies: the Taconic (480 million to 440 million years ago), the Acadian (415 million to 350 million years ago) and the Alleghanian (325 million to 260 million years ago), which together led to the assembly of the supercontinent Pangea.

The Acadian Orogeny had the greatest impact on this region of North America. The orogeny involved a continental collision that brought together Laurentia (proto-North America) and the Avalonia microcontinent; the collision extended from the Maritime Provinces in Canada south to Alabama, with the New England and Gaspé regions most affected. While the peak of the Acadian Orogeny is dated to the early part of the Late Devonian, deformation, plutonism and metamorphism continued through the rest of the period in the Gaspé region as a result of the prolonged and multiphased accretion of Avalonia to Laurentia.

The accretion of continental pieces onto Laurentia through the Devonian created massive folds and thrusts up and down the Appalachian Mountain belt, including the Gaspé Peninsula, as rocks trapped between colliding continents were forced upward. The Appalachians in their infancy would have appeared as rugged peaks, with elevations rivaling the European Alps. Erosion of these jagged mountains throughout the mountain-building process also distributed sediment into basins to the east and west of the mountain chain.

The Gaspé Peninsula is known for its richness of Devonian fossils, and is home to Miguasha National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site and a location of paleontological importance from the Devonian. The vast quantity of fossils in the Gaspé Peninsula today resulted from the continental collisions and the subduction of the Iapetus. In this process, the record of Devonian marine life that had been buried among sedimentary layers on the former seafloor was exhumed by the immense pressures exerted during the collision and distributed at varying elevations throughout the Gaspé Peninsula.

Whale watching is very popular along the Gaspé Peninsula. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/gwmyles.

A typical exploration of the Gaspé Peninsula begins along the St. Lawrence River, where the peninsula acts as the gateway to this waterway linking the interior of the North American continent with the Atlantic. In the early days of European settlement in North America, the St. Lawrence played an important role in the fur trade and in the defense of the interior against potential invasion from the United States.

The St. Lawrence River is relatively young, formed by glacial retreat 10,000 years ago, and it runs for more than 1,000 kilometers between Lake Ontario and the ocean. Today, the St. Lawrence Gulf, Estuary and River offer an abundance of marine life on display: Whale watching in particular draws thousands of visitors each year.

The St. Lawrence Estuary is one of the largest estuaries in the world, measuring 400 kilometers between Cap-Chat on the Gaspé coast and Île d’Orléans just upstream from Quebec City. It is part of the submarine Laurentian Channel that extends offshore 1,200 kilometers, and has a depth that varies dramatically between 300 meters and 20 meters at its head, between Les Escoumins and Tadoussac on the northern coast of the St. Lawrence River.

A typical exploration of the Gaspé begins along the St. Lawrence River. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/mirceax.

Where saltwater and freshwater collide, layers of water of varying salinity and temperature form, creating currents that allow small marine life like plankton and krill, which would normally be found in deeper waters, to move closer to the surface. For whales, dolphins, porpoises and seals, this creates a buffet of aquatic life. In summer months, beluga, minke, fin, blue, humpback, pilot, killer, northern bottlenose and northern right whales can be sighted along the coastline of the Gaspé Peninsula, where they spend weeks and months feeding on plankton to rebuild their fat stores.

A number of ferries run between the northern and southern coasts of the St. Lawrence. The crossing from Les Escoumins to Trois-Pistoles is one option for reaching the peninsula, dropping you off southeast of Rimouski, an area of the Gaspé full of lush vegetation and gentle terrain. The town of Grand-Métis, located north of Rimouski, is home to the stunning Jardins de Métis, a national historic site of Canada; and the surrounding region boasts a long history with geology, having been home to the renowned 19th-century geologist Sir J.W. Dawson, a close friend of Sir William Edmond Logan, who also frequented the area. The nearby Mitis River Park is a great spot to stop for a picnic lunch or to explore the collection of seashells from around the world.

The collection of seashells and fossils at Mitis River Park in Grand-Métis is one worth exploring. The extensive collection includes fossil specimens collected by the renowned geologist Sir J.W. Dawson. Credit: Amy Hogue.

Moving east up the northern coast of the Gaspé Peninsula toward Sainte-Anne-des-Monts, the topography of the peninsula undergoes a dramatic shift, transitioning from a low-lying coastal landscape to one of dramatic cliffs and mountains. The Appalachians are represented on the Gaspé by the Chic-Choc and McGerrigle mountains, both part of the Notre Dame Range though geologically distinct from one another. These mountains include some of the highest peaks in Quebec, with some exceeding 1,000 meters.

South of Sainte-Anne-des-Monts is Gaspésie National Park, home to two of the peninsula’s geologically significant mountains, which are worth exploring: Mont Jacques-Cartier and Mont Albert, both in the Chic-Choc Mountains.

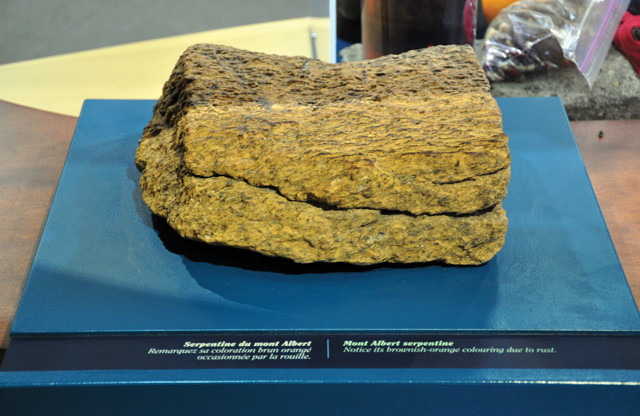

The orange coloration of this serpentinite from Mont Albert results from the high iron content in the rock. Credit: Amy Hogue.

Mont Jacques-Cartier is the higher and younger peak of the two. The rock of Jacques-Cartier formed underground about 380 million years ago as a large granite batholith. As the softer rocks around the batholith eroded, it remained, today reaching about 1,270 meters tall. Mont Albert, arguably the more interesting of the pair, formed at the end of the Ordovician, roughly 450 million years ago, and is a good example of an ophiolite — a section of Earth’s oceanic crust and mantle pushed up onto land.

Mont Albert has two summits: The higher one (1,154 meters) is South Albert, which is off-limits without a special permit and is separated from North Albert (1,088 meters tall) by a 13-kilometer-long plateau called Moses’ Table. Visitors can hike the Northern Trail, which offers a five-hour, 11.4-kilometer round-trip trek from the trailhead near the Discovery Center, or they can travel the full circuit, which includes the Northern summit, a portion of Moses’ Table, and the Devil’s Valley Trail. The full circuit is a six- to eight-hour hike of more than 17 kilometers.

The hike to the summit of Mont Albert affords spectacular views of the Chic-Choc Mountains, part of the Appalachians. Credit: Amy Hogue.

The Northern Trail offers hikers a good view of the Chic-Choc Mountains as well as a closer look at the ophiolitic rock that makes up the mountain. Serpentinite rocks found in ophiolite assemblages are often greenish in color, but at Mont Albert they are brownish-orange due to the oxidation of iron within the rock. Mont Albert happens to be one of the few places in North America where you can see this type of serpentinite rock exposed aboveground. It is also home to numerous rare plant species, two of which can only be found there, which is why South Albert is largely off-limits to visitors.

After leaving behind the mountainous Gaspésie National Park, head to Forillon National Park, which extends from the peninsula on a headland bordered by the Gulf of the St. Lawrence on its northern coast and the Gaspé Bay to the south. Forillon marks the northeastern terminus of the Appalachian Mountains in Quebec and preserves evidence of two phases of Appalachian mountain building: the Taconic Orogeny in the northern half of the park and the Acadian Orogeny in the southern half of the park.

An outhouse graces the top of Mont Albert in Gaspésie National Park. Credit: Amy Hogue.

A journey through the park offers glimpses of 10 geological formations spanning the Ordovician, Silurian and Devonian, all found within a small geographical region. Accordingly, fossils found in Forillon span these three periods as well, and bear witness to the effects of plate tectonics and evolution at the time.

The most easterly point of the park, Land’s End, is located at Cap Gaspé: The 15-kilometer-long Grande-Grave Trail will lead you along the park’s southern coastline to the “End of the World” and the picturesque Cap Gaspé lighthouse.

The unusual plateau at the top of Mont Albert is home to several rare plant species. The weather at the top of the mountain changes rapidly, but is typically cold, windy and foggy. Be prepared for snow on the ground, even during the summer months. Credit: Amy Hogue.

The Chic-Choc Mountains seen from halfway up the north side of Mont Albert. Credit: Amy Hogue.

To get a different perspective of the rock escarpments, seal habitats, and feeding grounds for whales and other marine mammals at Land’s End, you can tour the coastline in kayaks or zodiacs with experienced guides who will point out interesting sites from the water. It’s well worth the trip.

Next, head to the small fishing village of Percé, home to the awe-inspiring Percé Rock just offshore, one of the largest natural arches found in water. Named by Samuel de Champlain in 1607, Percé Rock (or Rocher Percé in French), literally translated, means “pierced rock.”

The 5-million-ton limestone monolith towers 88 meters high over the water. The limestone itself formed more than 400 million years ago during the Devonian; today, Percé Rock stands as an indicator of the vast tectonic forces that raised the rock and mainland from the seafloor, where it formed, to its current position above sea level.

At the mercy of erosion by the wind and sea, Percé Rock sheds approximately 300 tons of rock each year and is thought to have been connected to the mainland at some point in its history (it remains connected at low tide by means of an exposed sandbar). It is also reputed to have had three arches when it was discovered by Jacques Cartier in 1534; one of the arches must have collapsed between the 16th and 19th centuries, one collapsed in 1845, and one remains.

Today, Percé Rock is part of the Bonaventure Island and Percé Rock National Park, which covers about 6 square kilometers and includes a small section of the town of Percé, Percé Rock and the entirety of Bonaventure Island.

The so-called End of the World in Forillon National Park. This headland is bordered by the Gulf of the St. Lawrence to the north and the Gaspé Bay to the south. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Jeff_Rivard.

Percé Geopark, meanwhile, features more than 20 geosites, located either within the park or along the shoreline, and includes both Percé Rock and portions of Bonaventure Island. A stunning view of Bonaventure Island and Percé Rock can be seen from a glass platform located in the geopark suspended 200 meters above sea level. The glass-floored platform opened in 2017, and visitors can either hike to the platform or take the shuttle bus (fees may be required to access the platform and/or shuttle bus).

The lighthouse at the end of the relatively easy hiking trail, Grand-Grave, in Forillon National Park, is a popular resting place before beginning the downward trek all the way to Land’s End. Credit: Amy Hogue.

A boat excursion out of Percé is a terrific way to get a closer look at the entirety of Percé Rock and Bonaventure Island. Be sure to try the popular fish soup at the small restaurant on the island, Restaurant des Margaulx.

Bonaventure Island is a sanctuary for the northern gannett and is home to the largest colony of the birds in the world, harboring more than 100,000 in addition to other seabirds like puffins and razorbills.

Folded rocks exposed along Route 132 in Haute-Gaspésie, between Sainte-Anne-des-Mont and Forillon National Park, attest to the tectonic pressure once exerted in this region. Credit: Amy Hogue.

At one time, Percé Rock may have had three arches, although one reportedly collapsed in the mid-1800s, leaving an obelisk as a reminder of its existence. This arch is the only one remaining today, and although a small boat could pass through at the right time of day, the unstable nature of the rock makes it too dangerous to attempt. Credit: Amy Hogue.

The next stop on your tour around the Gaspé will take you to Chaleur Bay, where low-lying red rocks and calm coastal areas offer a relaxing change from the rugged cliffs and mountainous landscapes of the northern and eastern portions of the peninsula.

Miguasha National Park, on Chaleur Bay, is considered the world’s most outstanding representation of the Devonian. It is not to be missed. The seaside cliff face and roughly 87 hectares of Miguasha — it’s Quebec’s smallest national park — were designated as a national park in 1985 as a means of preserving the fossil-rich area that has been a location of worldwide interest since 1842. To date, more than 12,000 Devonian fossils have been discovered in Miguasha, many of which were removed prior to the area being protected.

Miguasha National Park protects the Escuminac Formation, a 370-million-year-old limestone formation rich with well-preserved fossils that tell the story of when fish were beginning the transition from water to land. Paleontological exploration of Miguasha continues to this day, and new discoveries are continually made as fossils wash up on shore or are exposed in the cliff face by erosion. In fact, fossils are discovered almost daily, but visitors are asked not to disturb new fossil finds and instead to inform park staff.

The first sight of Percé Rock makes an impression. Percé Rock sheds 300 metric tons of rock each year due to erosion, and in 16,000 years it will have eroded into the ocean completely. Credit: Amy Hogue.

An outcrop of the pre-Carboniferous basement rock called Le Mur Noir, the Black Wall, on Bonaventure Island is visible from the ferry. Credit: Amy Hogue.

The site of an ancient estuary, Miguasha is part of the Restigouche Syncline, and where the Restigouche River estuary joins the Chaleur Bay, its banks are made of sedimentary and volcanic rock from the Devonian. Evidence from the sedimentary layers, coupled with the presence of fossilized species found primarily in estuary environments, supports the interpretation that the Miguasha region experienced tidal influences in the Devonian.

Elpistostege watsoni, also known as Elpi, King of Miguasha: This 1.6-meter-long fossil was discovered by a park employee walking on the beach in 2010, but it took three years before the discovery was made public. This discovery makes Elpi the fish most closely related to humans ever discovered on Earth. Credit: Amy Hogue.

The contact between the Fleurant Formation and the lowermost sandstone beds of the Escuminac Formation is visible on the beach in Miguasha National Park, Together, the formations form the Miguasha Group. Credit: Amy Hogue.

The excellent preservation of so many fossils was made possible by two environmental factors: the rapid burial of organisms in the tidal estuary and the oxygen-poor conditions at the bottom of the estuary.

The formation of a tidal channel in the estuary would not only have trapped fish species in the current, but would also have carried sediment-laden water to cover them, and in some cases, fill their body cavities, creating ideal conditions for three-dimensional preservation. The hypoxic conditions at the bottom of the estuary are indicated by the abundance of pyrite in the sediments. The lack of oxygen protected specimens from decomposition and scavenging, and also created an environment for microbial communities that contributed to the rapid mineralization of specimens, in some cases even fossilizing blood vessels before they decomposed.

A Miguasha National Park naturalist explains that the cliff face on the beach in Miguasha contains layers of sandstone and clay, alternating to form a sequence 120 meters thick. Each of the layers is numbered to make it easier for staff to locate fossil-rich layers. Credit: Amy Hogue.

In 2010, a fossil specimen of Elpistostege watsoni (Elpi), a rare lobe-finned fish, was discovered lying on the beach by a Miguasha National Park employee. Only three specimens of this fossil are known worldwide: two held at Miguasha, including the only complete fossil found to date, and one at the British Museum in London. This fish is thought to be either one of the earliest tetrapods or at least related to the earliest tetrapods.

The fossil Elpi was discovered in Layer 12, which lies near sea level at the base of the cliff (left of the stairs). Efforts to preserve new fossil finds involve a constant struggle against erosion. Roughly 500 fossils are unearthed each year. Credit: Amy Hogue.

Your final stops along Route 132 should be the myriad wineries that pepper the landscape along the southern portion of the peninsula, and perhaps to fish for salmon along the world-renowned Matapédia River in the Valley region. Bring your appetite and savor the fresh local seafood found in virtually every restaurant or café on the peninsula as well.

class=““caption”>The best time to visit Gaspé is between May and October when whale watching is at its peak. Fly into Quebec City and rent a car, or fly into any of the smaller airports located throughout the peninsula. Plan for at least six or seven days to drive the route and experience the area. It’s advisable to book hotels or campgrounds ahead of time. You’ll find a number of campgrounds along the route, but stays at Gaspésie National Park, Forillon National Park, Bic National Park and Carleton-sur-Mer campgrounds will enhance the trip. Small inns, hotels and motels are also plentiful.

Route 132 is a winding road that borders the shoreline around the peninsula, making its way through scenic fishing villages and small towns. Credit: Amy Hogue.

Each of the provincial or national parks in Gaspé is phenomenal in their own way, with information centers and extensive hiking trails to explore. Though French is the official language in Quebec, most people speak English, and brochures and visitor centers offer information in both languages. Plan ahead and ask for a guided tour at Miguasha National Park to fully appreciate the bounty of fossils in the area and the significance of the discovery of Elpi. Be on the lookout for fossils. Perhaps you’ll be the next discoverer of an Elpi.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.