by Callan Bentley Wednesday, April 19, 2017

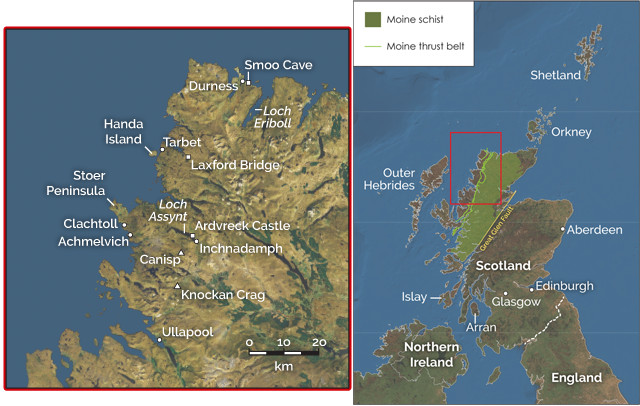

The North West Highlands of Scotland feature rugged mountains and gorgeous valleys with a rich geological history. Credit: Summer Brown.

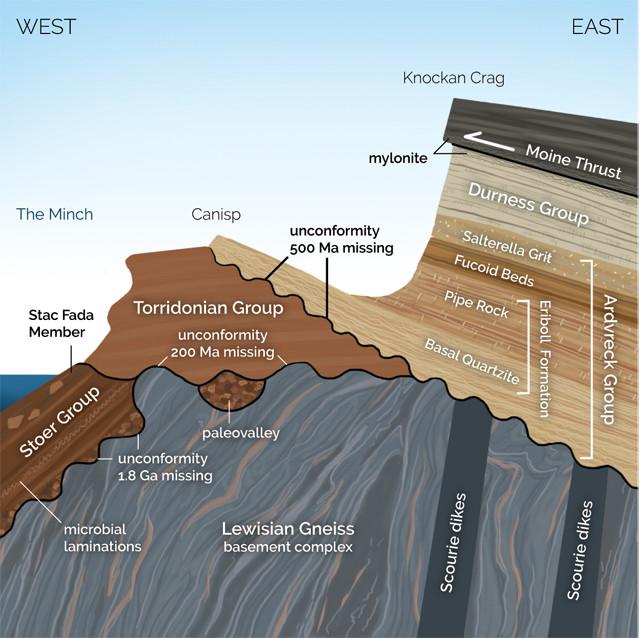

The North West Highlands of Scotland are sparsely populated, with rugged mountains and gorgeous valleys featuring a rich geological history. The area has the oldest rocks in the United Kingdom as well as some young landscapes freshly sculpted by ice sheets during the last glaciation. Early geological explorations and explanations of the North West Highlands proved perplexing and contentious, in part because the rocks of this region span two-thirds of Earth’s history in age. Additionally, there are, in places, sedimentary layers sandwiched between metamorphic packages of gneiss and schist. How did this happen? Was the schist deposited like a sedimentary rock atop the sandstone and limestone? Was it a former sedimentary layer that for some reason was exceptionally metamorphosed relative to the layers beneath it? Throw in three separate unconformities and the picture becomes even more muddied. You start to see why multiple generations of British geology students have traveled here for field camps.

The North West Highlands of Scotland hold an abundance of geologic features, but are easily explored in just a few days. Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI.

The complex geology of the North West Highlands, where the rocks span two-thirds of Earth's history, proved perplexing and contentious to early geologists, who found sedimentary layers sandwiched between metamorphic packages of gneiss and schist. Throw in three separate unconformities and the picture becomes even more muddied. Credit: Callan Bentley/K. Cantner, AGI.

Much of the early confusion over these rocks was solved by coming up with a few new concepts — namely, thrust faulting and mylonitization — of which the type locales can be found in the North West Highlands. The recognition of tricky faults parallel to the bedding (as seen in the famous Moine Thrust) was the key insight that solved the puzzle. These faults feature smeared-out rocks — “mylonite” — along their surfaces, a diagnostic detail that enabled geologists to recognize similar thrust faults all over the world.

The rocks in this region also show that Scotland used to be a piece of North America — or that North America used to be a piece of Scotland, from the Scottish viewpoint. They are so important to the history of geology that this area has been designated a UNESCO geopark: the North West Highlands Geopark. Beyond the exceptional geologic history, this corner of Scotland is also a delightful place to visit, far less besieged by tourists than the distillery-dotted locales farther south.

Mylonite is a highly foliated metamorphic rock composed of smeared-out, flattened minerals in a fine-grained matrix. It was first described near Loch Eriboll. Credit: both: Callan Bentley.

The North West Highlands has been recognized for its remarkable geology since at least the 1860s. One of the first prominent geologic descriptions of the area was by Scottish geologist Roderick Murchison, who described everything in the region as Silurian in age. (Murchison was obsessed with expanding the domain of the Silurian, a period he was the first to describe, so it’s best to take his characterization with a grain of salt.) Because the rocks were either metamorphic or barren sedimentary layers, he had little fossil data to countermand, or support, his bias. But there were complications with his interpretation. Murchison, for example, couldn’t explain how highly metamorphosed schist came to be laying atop unmetamorphosed sandstones and limestones. This conundrum didn’t bother him, however, and he reasoned that some of these layers must simply be more susceptible to metamorphism than others. Archibald Geikie, Murchison’s anointed successor in directing the British Geological Survey, toed the line established by his patron on the subject of the Highlands.

James Nicol, a geologist at the University of Aberdeen, disagreed with Geikie and Murchison’s descriptions of the region. In a paper in 1861, Nicol advocated a role for faulting, although not thrust faulting, which hadn’t been described yet. Nicol’s faults were steep, and featured prominently in the cross-sectional interpretations of his fieldwork.

In the late 1880s, Charles Lapworth got involved. He was a geologist at Mason Science College in Birmingham famous for first precisely delineating the boundary between the Ordovician and the Silurian using graptolites as index fossils. Lapworth suggested that the geology of the North West Highlands was far more interesting than a mere layer cake of anomalously metamorphosed layers. Lapworth’s detailed mapping of terrain around Loch Eriboll disproved suppositions stemming from Murchison’s model, and he benefitted from reading about other examples in the Alps and Appalachians of what are known today as fold-and-thrust belts. He suggested that movement along low-angle reverse faults, in which the fault plane is parallel to the bedding plane, had brought schists from east to west, overriding younger sedimentary strata. In other words, Lapworth invented the notion of thrust faults, and Eriboll is where he first deployed the mechanism to explain the North West Highlands' peculiar geology. Lapworth noted that rocks along the fault plane were smeared out and ground down to make new highly foliated and fine-grained rock, which he called “mylonite.” Eriboll is the type locality for that gorgeous beast.

Getting around on foot is a great way to travel throughout the region, but take precautions, like tucking in pantlegs and raising your hands, to avoid ticks. Credit: Summer Brown.

Lapworth didn’t solve the structural conundrums of the North West Highlands, but his work was the catalyst that made Geikie decide the survey needed to take another, more thorough look at the area. Survey geologists John Horne and Benjamin Peach were dispatched to conduct fieldwork in the North West Highlands. The detailed mapping by Horne and Peach was key to unraveling the enigma once and for all, and thrust faulting was the crucial ingredient in their interpretation. They were the first to decisively delineate the Moine Thrust and its parallel counterparts.

Since the thrust-faulting framework was established by Peach and Horne, additional details have been added, and isotopic dating of injected igneous units has constrained the timing of deformation. Researchers today are even dating recrystallization within the mylonites to derive dates of fault movement. The Highlands remain a hotbed for geological research, as well as a training ground for the next generation of British geoscientists.

Maps, GPS and a rental car are important for getting around the North West Highlands. Credit: all: Summer Brown.

Whether you’re a geologist or just have a general interest in really cool rocks, the North West Highlands is a great place to visit. You only need three or four days to see the most impressive rocks — though you could spend far longer — meaning a geology-themed trip to the area could easily be one excursion during a longer exploration of Scotland. If you want to spend longer, consider the Cape Wrath Trail, which isn’t a trail so much as a journey designed to take several weeks of walking from one end to the other of the North West Highlands.

Assuming you’re not walking the whole of the Highlands, you’ll want to rent a car and drive to the area from Fort William or Inverness. A ferry from the Orkney Islands is also an option. A range of lodging is available in the region — both in town and in the country — and it’s fun to move around and explore different places. We enjoyed the luxury of the high-end Torridon Inn in Torridon and Mackay’s Rooms in Durness for one night apiece, but based more of our stay out of the hostel-like setting of the Inchnadamph Lodge in Assynt, where many geological field camps base. In addition to saving money, this allowed us to cook our own food and make use of a sauna-like drying room to dehydrate our dampened boots at the end of each day.

Although many of the region's towns, like Durness, shown here, are small, they often have pubs and hostels or bed-and-breakfasts. Credit: Summer Brown.

Two issues plague the outdoorsy geotourist in the Highlands: the weather, which changes rapidly and can be excessively rainy, and tiny biting flies called midges. Good raingear will ameliorate the first, but long sleeves and gloves are the best protection against the latter.

The Scottish Outdoor Access Code (http://www.outdooraccess-scotland.com/) permits you to responsibly visit geological sites throughout the country, regardless of whether they are publicly or privately owned. So long as you’re not harming livestock or causing damage to any property (including with a rock hammer), there is no such thing as trespassing in Scotland. Roam free, geologists!

The North West Highlands Geopark (http://www.nwhgeopark.com) is a great resource for planning your visit. They offer guided hikes, interpretive programs, self-guided driving tours, and a “Rock Stop” cafe and visitor center overlooking Loch Glencoul at Unapool, south of Kylesku.

If you’re planning your excursion as a geological odyssey, two books to pack are: “The Highlands Controversy” by David Oldroyd, a readable scholarly summary of a century’s worth of geological thinking about the rocks of the Highlands, in particular the Moine Thrust; and “A Geological Excursion Guide to the North-West Highlands of Scotland,” edited by Kathryn M. Goodenough and Maarten Krabbendam, which is a lovely, full-color guide for the visiting geologist. What follows is my own brief guide for exploring the most important rocks of this region.

A small crag on Ben Arnaboll east of Loch Eriboll, where Charles Lapworth found the smeared-out rocks that led him to coin the term "mylonite." Here, a trace of a thrust fault that runs parallel to the famous Moine Thrust can be seen. (The Moine can also be seen at this location, just not in this photo.) Credit: Callan Bentley.

Durness, a small town on the northern edge of the North West Highlands, is a good home base for a day or two of exploration of Loch Eriboll and the adjacent coast. One of your first stops should be Ben Arnaboll east of Loch Eriboll; it’s the hill where Lapworth found the smeared-out rocks that led him to coin the term “mylonite.” You can also see the famous Moine Thrust, which crops out near the crest of the hills in the region, putting high-grade metamorphic rocks on top of limestones and quartz sandstones. Wandering these hills is a treat: You’ll see asymmetric rock outcrops called roche moutonnée (rock sheep), whose shape resembles the actual grazing sheep also inhabiting the area. Outcrops of mylonitized rock abound too, and tight folds can sometimes be spotted sandwiched between the smeared-out layers.

Tube-like Skolithos are trace fossils found in Cambrian and later sedimentary rocks. In the North West Highlands, they are the namesake of the Pipe Rock member of the Eriboll Formation (Ardvreck Group). Credit: Callan Bentley.

Smoo Cave and the cliffs outside its entrance feature a stack of about 10 packages of sedimentary rocks representing successive rounds of sea-level rise and fall. Credit: Callan Bentley.

The Cambrian and Ordovician limestones and dolostones of the Durness Group (mottled limestone with chert nodules) match up with near-identical carbonate strata in the Appalachian Mountains of North America. Credit: Callan Bentley.

Next, wander west of Eriboll to find the Cambrian and Ordovician limestones and dolostones of the Durness Group, which match up with near-identical carbonate strata in the Appalachian Mountains of North America. When Pangea broke apart in the early Mesozoic, a piece of the continent got ripped off and carried away — it became Scotland. Scotland is not only culturally different from the rest of the U.K., but tectonically different as well. The Durness rocks also feature stromatolites (fossil microbial mounds) in some places and host some “American” trilobite fossils.

Smoo Cave is a quick diversion right off the main road near Durness. A short walk down some stairs leads to the large cave entrance — at least 30 meters wide and almost 15 meters tall. It’s an interesting karst feature, and the inlet extending seaward seems to be a flooded solution valley, an indication that the cave used to be larger. Those interested in the cycles of sea-level rise and fall recorded in these carbonate rocks can stroll along the valley’s top, ogling the cliff exposures on the opposite side, which feature a stack of about 10 packages of shallowing-upward sedimentary rocks representing as many successive rounds of sea-level rise and fall.

The Lewisian Gneiss Complex near the coast by Tarbet, the departure point for Handa Island. Credit: Callan Bentley.

For your next bit of exploring, base yourself out of Scourie or Badcall, south of Durness. The near-nonexistent hamlet of Tarbet is the departure point for the ferry to Handa Island, a seabird-nesting colony with guillemots, puffins and razorbills, and a good place to drop off any traveling companions who would rather watch wildlife than clamber among rocks all day. The gneisses of the Lewisian Gneiss Complex are the prime geosightseeing target in this area. At about 3 billion years old, they are the oldest rocks in the North West Highlands, and they are easily accessed on the coast north of Tarbet. Local geologists refer to it simply as the Lewisian. These gneisses are gorgeous rocks, lurid pink and jet black mixed in countless combinations with white and gray. The Lewisian crops out in a characteristic landscape of rocky knobs interspersed with lakes known by the fun name “cnoc and lochan.” Once you are acclimated to the Highlands, you’ll know it at a glance.

Handa Island hosts a seabird-nesting colony. Credit: both: Greg Willis.

The Lewisian gneisses are cut by a suite of approximately 2.4-billion-year-old mafic and ultramafic dikes called the Scourie Dike Swarm. This feature is thought to have resulted from an ancient episode of tectonic stretching. A new round of deformation and metamorphism followed the Scourie dikes' intrusion about 1.7 billion years ago, and, as a result, the texture of the exposures varies tremendously from place to place. There are massive outcrops that appear to retain their original plutonic textures, and there are sheared-out zones where all the minerals have been flattened and aligned.

The "multicoloured rock stop" road cut north of Laxford Bridge perfectly shows the complexity of the Lewisian. Credit: Callan Bentley.

The “multicoloured rock stop” — a road cut — north of Laxford Bridge is a good place to try to wrap your mind around all this. The outcrop itself is a study in complexity. Utilizing the principle of cross-cutting relationships, tease out which of the many units came first, second, third and so on. There’s a reason they don’t call it the “Lewisian Gneiss Simple.” Use the nearby informational sign erected by Scottish National Heritage to check your answers.

Outcrops of Lewisian gneisses and black Scourie dikes can be seen at Clachtoll Beach. Credit: both: Greg Willis.

The shore of the North West Highlands is on a strait called “the Minch,” with the Outer Hebrides on the western horizon. There’s much to be seen along the coast here. A drive north along the Stoer Peninsula is a key excursion to a complete geotourism visit to the area.

The beach at Achmelvich is a gem — an idyllic cove with a well-regarded hostel and outcrops of Scourie dikes splitting the Lewisian gneiss on both headlands. In places, the dikes have weathered away, leaving corridor-like hollows with vertical walls. Stroll these corridors and contemplate the surging mafic magma that pulsed through them when Earth was half as old as it is today.

The beach at Achmelvich. Credit: Callan Bentley.

Just to the north is Clachtoll, the anglicized name for A' Clach Thuill, which means “split rock.” It is the best spot to examine the sedimentary strata of the Stoer Group, which includes the oldest fossils in the United Kingdom: 1.2-billion-year-old microbially induced sedimentary structures (like stromatolites, but in the Clachtoll Formation’s red sandstone). The fossils appear as crinkly, ultrathin layers of mud surrounded by, and disrupted by, sand. The shape comes from the way the grains of sediment were bound together by flexible, stretchy microbial mats resembling the skin that forms atop a warm pot of soup. Microbial mats like this are the sort of thing we might expect to find on Mars if life ever existed there, offering motivation for any future interplanetary geologist to take a good look and train their eye at Clachtoll.

Microbial laminations in the Stoer Group. Credit: Callan Bentley.

The presence of shocked quartz grains, elevated levels of iridium and nickel, and the mineral reidite in the Stac Fada suggests a bolide struck nearby. Green fragments are devitrified glass. Credit: Callan Bentley.

The Stoer Group sands and muds were deposited atop eroded Lewisian basement rocks, and the contact between the two rock units is an unconformity: Since the Lewisian’s youngest components are 1.7 billion years old, that means about half a billion years are missing along the unconformity surface. The unconformity has significant three-dimensional relief, and can be spotted by looking along the coastline for the coarse conglomerate that is lithified rubble: boulders and cobbles that were last tumbling along as loose pieces of sediment long before the first animals evolved. In one spot, reached by a short hike from Clachtoll south along the coast, there’s a beautifully preserved “paleovalley” filled with this conglomerate, nestled between Proterozoic “paleohills” of Lewisian gneiss.

The 1.18-billion-year-old Stac Fada member of the Stoer Group is an intriguing unit worth a look; it’s best seen at the little peninsula called Stac Fada, in the northern part of Stoer Bay. Some geologists interpret it as a volcanic mudflow deposit, while others think it’s a blanket of ejecta from a nearby meteorite impact. The presence of shocked quartz grains, elevated levels of iridium and nickel, and the mineral reidite in the Stac Fada strongly supports the impact hypothesis, but the abundant chunks of greenish volcanic glass and accretionary lapilli could result from either a volcanic eruption or an impact. The Stac Fada also contains bizarre “rafts” of folded sandstone layers, whose anomalous location and deformation suggest they got shoved into place by a violent force. Geophysicists have recently delineated a circle of low gravity 40 kilometers to the east, which suggests an impact crater. Unfortunately, we cannot say for sure as any remnants are hidden from view, protected from direct inquiry under the shield of the Moine Thrust sheet.

A paleovalley cut into the Lewisian is filled with Stoer conglomerate that is 1.8 billion years younger than the Lewisian. Pete Harrison, a North West Highlands Geopark guide, sits at the left edge of the unconformity. Credit: Callan Bentley.

Stags near Loch Assynt (top) and Ardvreck Castle (bottom). Credit: Credit: both: Callan Bentley.

Base your final stay in the North West Highlands in the town of Assynt along the shore of Loch Assynt, the nucleus of the geologist’s North West Highlands. This freshwater lake trends east-west across the north-south structural trend of the rocks. Hence, by driving inland from Achmelvich to Inchnadampf, you cross many of the major rock units of the area.

This area hosts two more unconformities to marvel at: On Assynt’s northern shore, the Proterozoic-aged Torridonian red sandstones were laid down over the Lewisian basement rocks, leaving a 2-billion-year gap. The contact between these two units can be examined in roadside and loch-shore outcrops. Gazing south across the lake, you can see another unconformity, where the sandstones of the Cambrian-aged Eriboll Formation dip gently eastward off the east slopes of the mountain called Beinn Gharbh. The bulk of Canisp is Torridonian, implying 500 million years of erosion between the two units. But their relative orientation implies something moderately bizarre: that the Torridonian rocks were first deposited, then lithified, then tilted about 15 degrees to the west, then eroded down, then the quartz sands of the Eriboll Formation were deposited, then lithified, then the whole package was tilted 15 degrees back to the east, returning the Torridonian to more or less its original horizontal orientation in the process! The fact that both episodes of tilting were the same magnitude, but in opposite directions, is unique in my experience.

Also along Loch Assynt’s shores lie the ruins of the 16th-century Ardvreck Castle. After clambering up its ruins, visitors can gaze over a panorama that includes outcrops of the famed Cambrian-aged Ardvreck Group, a collection of sedimentary formations mapped by most British geology students in their field camp experiences. The coolest thing about the Ardvreck Group is it shows the same sequence of sedimentary rock types of the same age as the North American continent. Whether you’re in the Appalachian Mountains, the Grand Canyon or the North West Highlands of Scotland, Cambrian and Ordovician rocks show a near-identical sequence of sandstone, shale and limestone that records a global rise in sea level. You can view these along Loch Assynt in road-cut outcrops of the various units, some of which show “bonus” features like igneous intrusions and faults.

A double unconformity can be seen on Beinn Gharbh: 500 million years is missing between the Eriboll Formation and the Torridonian and Lewisian, and 200 million years is missing between the Torridonian and Lewisian. Credit: Callan Bentley.

On the road from Assynt to Ullapool, check out a classic outcrop of the Moine Thrust at Knockan Crag. This hillside has been well developed as an interpretive site with numerous sculptures in addition to the geological attractions. A rock wall showing the relevant rock units greets you. It’s a great opportunity to examine slabbed and polished specimens of the various members of the Ardvreck Group: You can see the many “worm” burrows that give the Pipe Rock its name, or the tiny cone-shaped fossils called Salterella, which are the namesake of the Salterella Grit.

Knockan Crag visitors can continue uphill to a life-sized set of statues of the British Geological Survey geologists Peach and Horne, and press a button to hear them (well, actors) discuss their work in the Highlands and on this very hill. A covered kiosk stands nearby with informative displays and a clever rendering of the landscape in cut glass where audio yields the correct way to pronounce the names of the landscape features in Scottish Gaelic. Full of newfound understanding, visitors can then hike up the hill to a series of outcrops of the Moine Thrust itself, with its namesake schist thrust over Durness limestone. There is a 500-million-year difference in their ages, and the older one is on top!

The rock wall (top) showing many of the rocks in the region, the Moine Thrust (both middle pictures) and mylonite (bottom) all seen at Knockan Crag. Credit: all: Callan Bentley.

Among structural geologists, the Moine Thrust is legendary. To stand there, with your finger on this ancient horizontal fault plane, is to commune with the minds of Peach and Horne and Lapworth. This is the cradle of a vital concept in tectonics, without which we’d have a much harder time explaining places like the Himalayas and Glacier National Park in Montana. In that sense, a visit to the North West Highlands is not only a delightful recreational sojourn, but, for a geologist, an intellectual pilgrimage as well.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.