by Mary Caperton Morton Monday, June 11, 2018

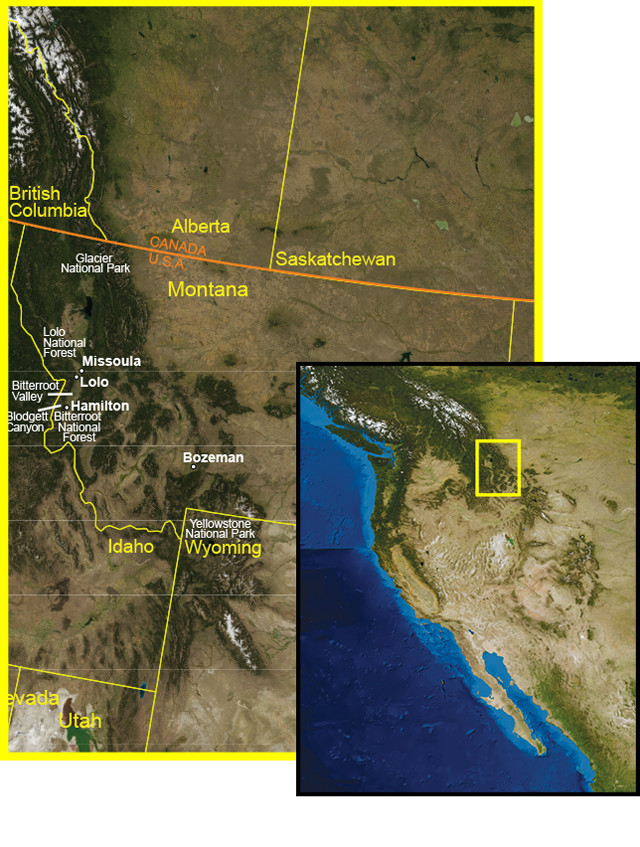

Everything is big in Big Sky country: big mountains, big rivers, big glaciers, big floods and big bears. Montana itself is such a big place that it would take a lifetime to explore the whole state, so visitors are better off picking a few hot spots. Glacier National Park in far northern Montana may be the state’s most popular tourist destination, but Missoula and the Bitterroot Valley, a scenic four-hour drive south of the park, should also top any geo-traveler’s must-see list.

Today Missoula is the culture capital of Montana, home to the University of Montana’s main campus, numerous museums, a vibrant music scene and a variety of quirky vintage stores along the “Hip Strip.” However, not so long ago, the entire valley was submerged beneath a great lake known as Glacial Lake Missoula. About 15,000 years ago, a southward advancing lobe of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet dammed the Clark Fork River west of Missoula, where it now flows into Idaho’s Lake Pend Oreille, creating a huge lake that contained more water than Lake Erie and Lake Ontario combined.

High-water marks from the 600-meter-deep lake are still visible on the mountainsides around Missoula. The best way to see the marks, and get a bird’s eye view of the entire Missoula Valley, is to climb the famous “M” trail above the university campus. Visible from almost anywhere in town, the university’s century-old concrete “M” is reached by a zigzagging trail that rises 200 meters up Mount Sentinel. From the top, the view of the Missoula Valley is stunning. Five valleys and three major rivers converge here, and the entire region is surrounded by mountain wilderness preserved by the Rattlesnake Wilderness and the Lolo and Bitterroot national forests.

Credit: AGI/NASA

From your vantage point atop Mount Sentinel, find the Clark Fork River, running west through town, and follow it to the horizon. This now placid river valley was once the scene of some of Earth’s greatest flood catastrophes. Between 15,000 and 13,000 years ago, the ice dam holding back Glacial Lake Missoula burst dozens of times, unleashing massive floods that barreled across the northwestern United States all the way to the Pacific Ocean, leaving mega-ripples across the landscape. Glacial Lake Missoula’s sheer size and high elevation contributed to a tremendous rush of water 10 times greater than all the world’s rivers combined. The onslaught scoured eastern Washington into the bare Channeled Scablands that they are today, and carved much of the modern Columbia River Valley.

South of Missoula, the landscape opens up into the Bitterroot Valley. On a clear day, the jagged peaks of the Bitterroot Range visibly line the west side of the valley, straddling the Continental Divide and Montana’s border with Idaho. When Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and their team journeyed through Montana in the spring of 1805 on their way to the Pacific Ocean, they came through the Bitterroot Valley on the Bitterroot River. To pick up their trail, climb back down from the M and hop in a car or on a bike and head south out of town on scenic Highway 93.

The Bitterroot Valley, lined on the east by the rolling Sapphire Mountains and on the west by the imposing Bitterroot Range, is named for Montana’s pink state flower. Small towns dot the narrow north-south running valley, and agriculture and ranching still dominate the area’s economy. Tourism is also a mainstay here. A number of ranches cater to guests and a night at the Chief Joseph Ranch or Skalkho Ranch is a great way to experience life in the valley.

When Lewis and Clark reached this valley more than 200 years ago, they came from the south, over Lost Trail Pass. Upon reaching what is now the tiny town of Lolo, just 15 kilometers south of Missoula, they stopped for a well-deserved break at a spot they called Travelers’ Rest. To visit their historic camp, turn west off 93 onto Highway 12, and follow the signs for a few kilometers to Travelers’ Rest State Park. This is one of the few Lewis and Clark sites where historical artifacts and physical evidence of their camp have been uncovered, and the park has preserved this unique site with a small museum and an interpretive walk.

From Travelers’ Rest, Lewis and Clark continued west on Lolo Creek over Lolo Pass into Idaho. It’s about an hour drive to the Idaho border from Highway 93, and a visitors center at Lolo Pass is a great waypoint for more information about their historic journey. Be sure to stop by Lolo Hot Springs, where Lewis and Clark — and generations of Salish Indians before them — came to soak in the geothermally heated mineral waters.

After your side trip into Idaho, head back to Highway 93 to continue down the Bitterroot Valley. South along Highway 93, you’ll parallel the famed Bitterroot River. Immortalized in former Missoula resident Norman Maclean’s classic book “A River Runs Through It,” the Bitterroot is considered one of the world’s great fly-fishing rivers. Every couple of kilometers along the highway, good fishing spots are marked with brown public access signs. Equipment, licenses and fishing guides are available at any of the dozens of fly shops in Missoula and along the road. This is no place for bait fishing.

Top: Ranch in the Bitterroot Valley. Bottom: The author at Glen Lake. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton

West of the river is the commanding Bitterroot Range. One of the most rugged stretches of the Rocky Mountains, the Bitterroots are composed of granite shed from the Idaho batholith (a large granite intrusion) and carved into jagged, 2,700-meter-high peaks by glaciers during the last ice age. Hanging valleys, cirques and alpine lakes dot the glacial terrain. The range is so rugged that even today, the only way into the mountains in this area is on foot; you have to drive 140 kilometers south from Lolo to find another road into the mountains.

Fortunately, for those who want to see the Bitterroots up close, more than 2,500 kilometers of trails lead up into the peaks, almost all following scenic river canyons. Dozens of snowmelt-fed streams cascade out of the Bitterroots’ many alpine lakes into the river below. These mountains receive as much as 12 meters of snow per year and spring runoff can be torrential — a small reminder of the strength of the ancient Missoula Floods.

The most scenic of these canyon trails follows Blodgett Creek through stunning Blodgett Canyon, west of the town of Hamilton. The sheer granite cliffs of the Prinze Ridge to the north and Romney Ridge to the south tower 1,200 meters above the river, and any length hike down the easy-to-moderate trail is sure to leave you with a scenery-induced crick in the neck. Good fishing spots abound along the trail, and a series of waterfalls about five kilometers in is a great spot to picnic or camp. Keep an eye out on the cliffs above for mountain goats and human rock climbers; Sky Pilot, a lightning rod of a peak, is renowned as one of the world’s toughest climbs.

Downtown Missoula. Credit: Digital Vision

Bull riding at the Western Montana State Fair in Missoula. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton

Biking is a popular way to get around in the Bitterroot Valley. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Christian Sawicki

Blodgett Creek is fed by Blodgett Lake, an alpine lake more than 2,200 meters above sea level. The 37-kilometer-long roundtrip trek to the lake is well-suited for adventurous backpackers, but those looking for a more accessible alpine lake should try the Glen Lake trail, a few kilometers north near the picturesque town of Victor. This 7-kilometer-long roundtrip hike is also a great place to witness the aftermath of a forest fire that swept through this region just a few years ago. The Gash Creek Fire burned more than 3,200 hectares during a particularly bad fire season in 2006. Four years later, much of the lodgepole pine, subalpine fir and larch is charred, but wildflowers and young trees abound, a testament to the renewing power of fire. After your hike, top off your trip with a visit to the Smokejumper Base and Museum near the Missoula International Airport to learn more about Montana’s history of fire and its long-term ecological benefits. Montana is one of the last places in the United States to still employ smokejumpers to put out forest fires. The parachuting firefighters are still needed because much of Montana’s backcountry remains true roadless wilderness.

Hiking into the Bitterroot Range is a great way to see some otherwise inaccessible geology, but be prepared. During my summer in Montana, I came face to face with a grizzly, was awoken by wolves howling outside my tent, got charged by an angry mother moose and had three of my favorite trails closed due to a raging wildfire, a marauding black bear and a putrid dead horse.

If you pack a good map, carry bear spray and use common hiking sense, a trip to Missoula and the Bitterroot Valley is sure to be a great geologic adventure.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.