by Bethany Augliere Wednesday, February 13, 2019

The largest of the 30 springs at Florida's Silver Springs State Park is called Mammoth, or Main, Spring. No swimming is allowed here, but visitors can view the spring from a glass-bottom boat tour. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

As a child, my family and I often traveled to Florida to escape the chilly Virginia winters and enjoy the Sunshine State’s warm sunny beaches. Occasionally, we’d make a trip to Orlando to visit one of the theme parks or stop at Everglades National Park to search for alligators, snakes and birds.

The idea of swimming in such dark, alligator-filled freshwater never occurred to us. Wouldn’t that be dangerous? It wasn’t until years later, when we camped at Ginnie Springs, a freshwater spring and underwater limestone cave system tucked in the forests of North Central Florida that is a popular swimming and diving site, that I realized how wrong we had been.

I’ve lived in South Florida for almost a decade, and exploring the state’s crystal-clear freshwater springs and rivers is now one of my favorite parts of living here. Florida’s freshwater can be enjoyed by everyone, whether you are a cave-certified scuba diver, are on the hunt for fossils, or you and your family are just looking for a vacation from Florida’s more crowded beaches and theme parks.

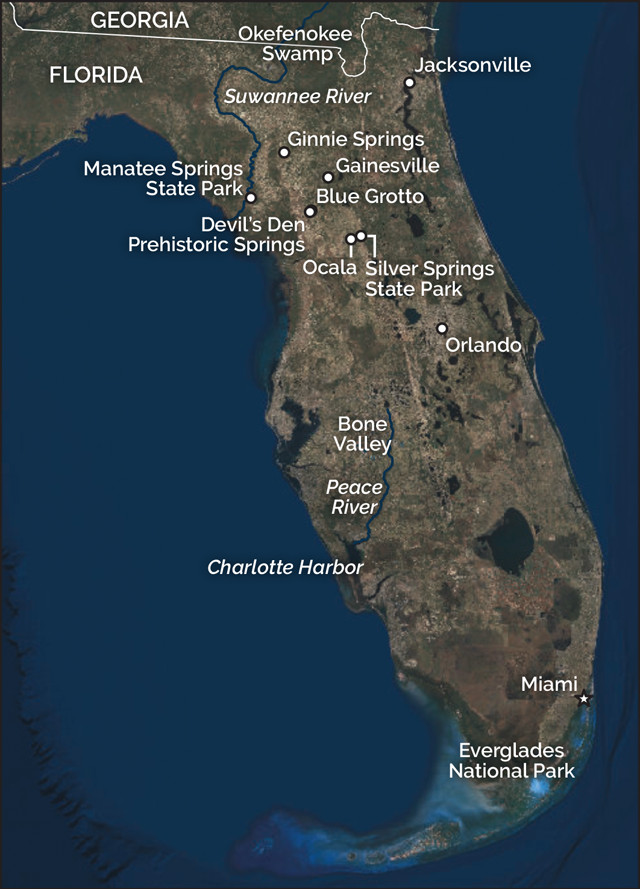

Florida's karst limestone geology and shallow water tables result in an abundance of freshwater springs. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

Florida is home to about 900 springs, which dot the landscape between the state’s east and west coasts, though most are in North and North Central Florida. I’ve visited a few dozen of them myself, and each one has something unique to offer.

Florida has possibly the highest concentration of springs in the world, due to the state’s geology and climate. The state is underlain with porous limestone and receives a lot of rain. When the mildly acidic rain falls to the ground, it dissolves the underground limestone over millions of years, creating water-filled caverns and tunnels. Springs form when subsurface pressure forces groundwater up through an opening to the land surface.

Walking up to a Florida spring feels like entering another world. The clear, inviting waters are often bright aqua or deep blue, surrounded by green vegetation both in and out of the water. After diving in a spring, famed underwater explorer and filmmaker Jacques Cousteau described the experience as “no wind, no waves, and visibility forever.”

On a sunny summer day, the springs’ constant year-round temperature of 20 to 22 degrees Celsius offers welcome relief from Florida’s heat and humidity, though the springs are more crowded than in winter. In winter, the springs are relatively empty, giving visitors a reprieve from the throngs of snowbirds and theme park-goers. Winter is also the best time for chance encounters with manatees, as they enter the springs (many of which are hydrologically connected to coastal waterways) to seek refuge from the cooler ocean and river waters.

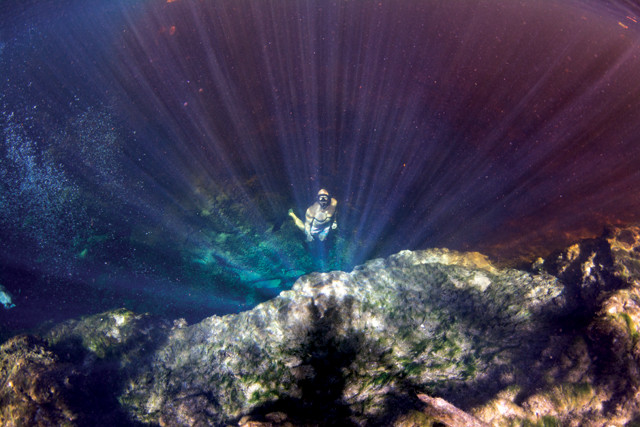

A freediver checks out Devil's Ear Spring at Ginnie Springs in High Springs, Fla. The area of dark water shows where the spring meets the tannin-rich waters of the Santa Fe River. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

One of my favorite springs is Manatee Springs State Park, located in Chiefland, Fla., about 200 kilometers northwest of Orlando and 65 kilometers west of Gainesville. It’s one of 33 first-magnitude springs, which means the groundwater flows to the surface at more than 2.8 cubic meters per second. It’s also one of Florida’s largest springs, releasing an average of 443,000 cubic meters of water daily.

The spring is almost 8 meters deep at its deepest point, with a visible “boil” at the bottom where sand percolates as water bubbles up through the floor of the spring. It also has nearly 8,000 meters of mapped cave tunnels, making it one of the longest-known underwater cave systems in North America. If you’re not a certified cave diver (see sidebar, page 50) it’s still a great place to swim and snorkel to look for freshwater wildlife like turtles, fish and even (harmless) water snakes.

The author photographs a resting manatee. Manatees enter the springs during winter to rest and seek refuge from cooler ocean and river waters. Credit: Nicodemo Ientile.

If you don’t feel like taking a dip in the cool water, 13.5 kilometers of nature trails wind through the woods, and there is a 245-meter-long elevated boardwalk through the floodplain forest, following the spring out to the connecting Suwannee River, which flows from Okefenokee Swamp in southern Georgia to the Gulf of Mexico. Visitors can fish in the river, as well as rent canoes and kayaks.

One of the more distinct Florida springs is called Devil’s Den in Williston, about 50 kilometers southeast of Manatee Springs and a 30-minute drive from Gainesville. Privately owned but open to the public, this is an underground spring inside a dry cave, with an opening to the surface above. Its name comes from early settlers who saw plumes of condensing steam rising from the opening as the warm water met the cool air.

The spring formed in a geomorphic event known as a karst window, which occurs when carbonate bedrock above a subterranean river or spring collapses into a sinkhole, exposing the groundwater to the surface.

The diveable pool at Devil's Den Spring reaches a depth of 16.5 meters and is shaped like an inverted mushroom. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

Devil’s Den is another great spring at which to snorkel and scuba dive. The diveable pool of the spring reaches a depth of 16.5 meters and is shaped like an inverted mushroom. Small entrances to caves at the bottom of the pool are sealed off by safety grates. Without proper training, it’s easy to stir up silt in an underwater cave, lose visibility and become disoriented. With no way to easily surface, any misstep can quickly turn deadly.

Devil’s Den is also a recognized prehistoric site, with fossils found in the cavern dating to the Pleistocene Epoch. Remains include the bones of mastodons, giant ground sloths, Florida spectacled bears and saber-toothed cats. Human remains dating to 7500 B.C. have also been found. Some of the fossils are on display at the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida in Gainesville, as well as at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. I didn’t see anything quite so exciting when I went diving at the site last spring, but I did see outlines of fossilized sea biscuits and urchins in pieces of limestone.

Just 4 kilometers from Devil’s Den is another privately owned spring called Blue Grotto. While you can snorkel the main pool area, this spring is geared more toward scuba divers. The underwater cavern within the spring is 24 meters wide and reaches a depth of 30 meters underground.

Blue Spring State Park is a popular year-round destination for swimming and kayaking. Credit: both: Bethany Augliere.

Virgil, the female Florida soft-shelled turtle that has lived in Blue Grotto Spring for more than 20 years, cannot leave the spring and has become habituated to humans. Divers can feed her food pellets purchased at the dive shop. Credit: both: Bethany Augliere.

Blue Grotto is also known for its most famous resident, a female Florida soft-shelled turtle named Virgil. While these turtles are typically shy and wary of humans, Virgil has lived at the spring for more than 20 years and has become habituated to people.

About 50 kilometers southeast of Devil’s Den and Blue Grotto is Florida’s largest spring, which lies inside Silver Springs State Park in the city of Ocala. This is not the place to visit if you are looking for a remote wilderness experience, because the park feels almost like a small town, with a museum and educational center, a gift shop, a restaurant, and an ice cream and fudge shop. However, it’s family friendly and offers a lot of activities to choose from, including hiking, biking, horseback riding, kayaking and tours aboard glass-bottom boats that have been in operation for 100 years.

There is no swimming allowed in the springs, but the largest spring, Mammoth Spring, can be viewed on a glass-bottom boat tour. Visitors can glimpse Ocala Limestone, a chalky, white carbonate rock deposited roughly 35 million years ago, which holds an abundance of fossils.

A view of the surface of Blue Grotto Spring in Williston, Fla. Credit: Nicodemo Ientile.

I toured Silver Springs State Park in hopes of sighting members of the wild troupe of rhesus macaques that calls the park home, but was unsuccessful. The monkeys were introduced to the park about a century ago as a tourist attraction. However, they could soon get the boot, according to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission. New research has shown that they carry a dangerous type of herpes virus that could spread to humans via their feces or bodily fluids.

While many of the springs in Florida appear pristine and healthy, they all face threats from human activities such as water withdrawals — for drinking water, agriculture, development and industry — and pollution, which is introduced by stormwater runoff. One particular concern is the input of nutrients from fertilizers and pesticides, which lead to algal blooms that deplete oxygen and can choke out native vegetation, like eel grass. Manatee Springs, for instance, is now covered with invasive algae.

Rivers constitute another of Florida’s freshwater ecosystems worth visiting. In southwestern Florida, the Peace River runs south for 171 kilometers and empties into the Charlotte Harbor Estuary near Port Charlotte. Its drainage basin covers 6,046 square kilometers of Florida as it meanders through pine flatwoods, palmetto prairies and cypress swamps before reaching the estuary.

The river is fed by springs, but is technically a blackwater river, which means it drains pine flatwoods and cypress swamps, resulting in dark waters from decomposing plant material. The riverbed consists of layers of sand, clay and limestone particles.

In the early 1500s, an unnamed Spanish cartographer named the river Rio de la Paz, or River of Peace. Two centuries later, Seminole Indians settled the area and called the river Tallakchopo, or the River of Long Peas, possibly as a mistranslation of the Spanish name, or perhaps because wild peas grew along the bank.

A school of ladyfish swims in Silver Glen Springs in Ocala National Forest. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

Invasive algae chokes out native vegetation in Manatee Spring at Manatee Springs State Park. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

In the 1800s, the river became a profitable resource when formations of valuable — and abundant — phosphate minerals were found near its course. The layers of sedimentary phosphate rock formed underwater between 26.5 million and 5 million years ago when Florida was submerged during the Miocene Epoch. The region also acquired its modern nickname — “Bone Valley” — in the 19th century because of the numerous fossils discovered in the phosphate deposits.

Bone Valley is a popular tourist destination for camping and searching for fossils, like shark teeth and dugong ribs. The now-extinct Florida dugong was a cousin of the manatee but lived exclusively in saltwater. Unlike the paddle-like tail of a manatee, dugong tails were V-shaped like those of modern whales. The Florida dugong became extinct about 2.5 million years ago. Today, dugongs only exist in the waters off Australia, East Africa and parts of Asia.

Fossil-hunting on the Peace River yields many shark teeth, including a juvenile megalodon tooth. Credit: both: Bethany Augliere.

The best way to collect fossils is by canoeing or kayaking down the river, although if you’d prefer to stay off the water, you can walk along the shoreline as well. There are several options for canoeing the river, including day trips and overnight trips, which start farther upriver. If you decide to camp, the main outfitter, Canoe Outpost, will shuttle you and your gear to a campground. And then you can take your time paddling back to the outpost. If you’re not camping, you can take a bus to a spot upriver and spend the day paddling back.

To search for fossils, a shovel and sifter will come in very handy (though you can scoop and sort with your hands if you don’t mind getting messy). You can rent or buy these items at the Canoe Outpost. As you paddle down the river, stick your shovel in the riverbed sediment occasionally. If it’s gravelly and crunchy as opposed to sandy, that’s a good place to look. Beach your canoe, then start scooping up some gravel, and place it in the sifter to wash away mud and sand.

The most common fossils to find are shark teeth, which are fairly obvious. Small teeth are abundant, but a tooth from a giant megalodon is what everybody is after, though they are less common. I was lucky enough to find a small megalodon tooth along with many other shark teeth, dugong ribs, which are also common, a fossilized alligator jawbone and tooth, and a horse tooth.

My family’s occasional trips to the Everglades notwithstanding, it took me a long time to get to truly know Florida’s freshwater ecosystems: By now, I have even snorkeled in the cypress swamps of Everglades. And while I have yet to come across an alligator there, I’m hopeful that I someday will. I still love the state’s beaches and marine life, but exploring its springs, rivers and wetlands has shown me an entirely different side of Florida — one that I’d recommend to any nature-loving traveler.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.