by Bethany Augliere Thursday, February 16, 2017

At about 1,605 meters, Mount Katahdin in Baxter State Park is the highest mountain in Maine. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

After weeks of anticipation and constant checks of weather forecasts to find a day when the skies were likely to be clear, I decided the early fall morning had finally arrived to hike Mount Katahdin — the highest mountain in Maine at 1,605 meters. I woke up at 5 a.m., crawled out of my sleeping bag, got dressed and turned on my headlamp to begin the trek.

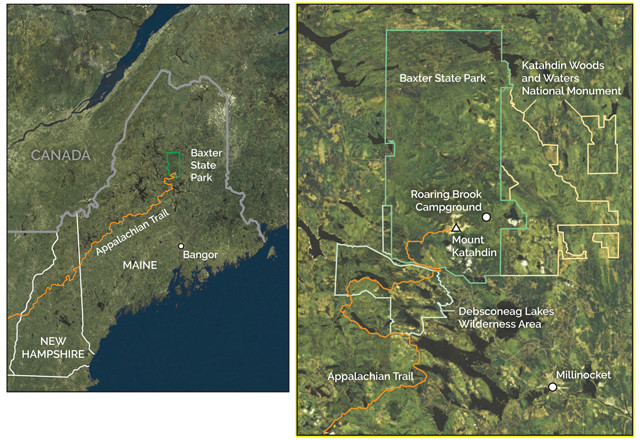

Katahdin, pronounced “kuh-TAW-din,” was named the “The Greatest Mountain” by the Penobscot Indians — a fitting designation. It’s the crown jewel of Baxter State Park, more than 80,000 hectares of wilderness and public forest in north-central Maine, and the northern terminus for the 3,500-kilometer-long Appalachian Trail, which begins on Springer Mountain in Georgia and crosses 14 states. After chatting with locals and park rangers, I got the sense that no matter which of the routes you take up the mountain, it’s a long hike and people tend to underestimate it.

In early October, when my hiking companion, Nico, and I were there, temperatures can drop to minus 6 degrees Celsius at night. It’s not uncommon for people to get lost, or to start too late and end up hiking in the dark. In rare instances, visitors to Katahdin have tragically succumbed to the elements: Since 1926, 22 deaths have occurred on the mountain. Even as an experienced hiker, I took Katahdin’s reputation seriously. My pack included a 3-liter hydration bladder, an extra water bottle, food, an emergency blanket and extra layer of warm clothes, and a small first aid kit.

We registered at the Roaring Brook Campground ranger station with our time of departure and planned route up the mountain. It would be about a 15-kilometer round-trip journey, with a 1,214-meter elevation gain. It was 5:30 a.m., and three other hikers had already started from this location.

Chimney Pond is a small circular lake, called a tarn, found on the east side of Katahdin and a 5.3-kilometer hike from Roaring Brook Campground. From here, hikers can view the steep mountain slopes carved from glacial erosion. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

At first glance, the jagged, treeless mountain resembles a volcano. Its rock, part of a granite pluton, is indeed magmatic in nature, having solidified before it reached Earth’s surface. In fact, it’s part of a laccolith — a mushroom-shaped granitic intrusion — that formed about 400 million years ago during the Acadian Orogeny, a major period of mountain building that affected the Appalachian chain from present-day Virginia to Newfoundland and lasted for 150 million years. This happened as the microcontinent Avalonia collided with North America at the leisurely rate of 5 kilometers per million years.

Over time, Katahdin has been shaped by weathering and erosion, especially during glacial periods. Alpine glaciers carved deep bowl-shaped depressions, or cirques, into its flanks. Other glacial features such as kettle ponds, moraines and eskers are scattered throughout Baxter State Park.

Katahdin has five peaks: Howe, Hamlin, Pamola, South and Baxter, the summit. Between Baxter and Pamola peaks is a narrow 1.7-kilometer-long boulder-scramble along a glacial arête called the Knife Edge, which, at points, is only a meter wide. This adventurous traverse was the primary reason I wanted to hike Katahdin.

Mount Katahdin in Baxter State Park is about 120 kilometers from Bangor, Maine. Credit: both: K. Canter, AGI.

On a trip to Baxter State Park last summer, we explored some of the other 320-plus kilometers of maintained trails in the park, which has no running water, electricity or paved roads.

The rugged nature of the park is maintained “for those who love nature and are willing to walk and make an effort to get close to nature,” as park donor and former Maine Governor Percival P. Baxter put it. He purchased the land in 1931 to protect it from logging and deeded it to the state with instructions that it “shall forever be retained and used for state forest, public park, and recreational purposes … shall forever be kept and remain in a natural wild state … [and] shall forever be kept and remain as a sanctuary for beasts and birds.”

Being one end of the Appalachian Trail, the state park is known for its hiking, but it also offers plenty of other options. Visitors can whitewater raft, or canoe, if a more leisurely pace is desired, down the Penobscot River. Berry-picking is a very popular activity in the summer, as is moose-viewing at Sandy Stream Pond and other wildlife watching. Additionally, a short drive away is one of America’s newest national park sites — Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument — designated by President Obama on Aug. 23, 2016.

But we were there to hike, so we found a couple of trails we could follow for a day to take in some great views and potentially spot some moose.

For our first stop, we decided to explore Blueberry Ledges, a 6.75-kilometer round-trip hike. To get there, we turned off the main road into the park for the Golden Road, a logging road that is marked by a giant painted rock. We followed this dirt road for 16 kilometers, scanning the ponds for moose along the way (alas, we didn’t see any).

The hike began on the Appalachian Trail. We crossed a small bridge over a section of Abol Stream, with a view of Katahdin towering over the valley.

The beginning of Blueberry Ledges was a narrow path through stands of aspen and birch trees. At the end, the trees opened up to flat slabs of granite, forming rock highways flanked by blueberry bushes. We lay in the water to cool off, ate blueberries, and walked around the cascading stream. We had this spot to ourselves — a degree of solitude can be a hard thing to find at other parks, like nearby Acadia National Park.

An easy trek along the Ice Cave Trail ends at a pile of boulders where hikers can climb down into a cool cave with patches of snow and ice left over from the previous winter. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

After drying off in the sun, we packed up to visit our next stop: ice caves. This was a quick and flat 4.8-kilometer round-trip hike in the Debsconeag Lakes Wilderness Area, owned by the Nature Conservancy and adjacent to the state park. This area contains the highest concentration of pristine ponds in New England, and thousands of hectares of mature forest.

The trail to the ice caves meandered through tall pines and moss-coated boulders, with a mild elevation gain.

Eventually we reached the caves’ entrance tucked away among a giant boulder garden. The ice caves are actually just open spaces amid the boulders of a talus slope — rocks cleaved off nearby cliffs during the last glaciation — piled together such that they create cave-like features.

A view of Katahdin and whitewater rafters on the Penobscot River from the Abol Bridge. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

We approached the “cave” opening and climbed down steel rungs into the chilly room, quickly realizing how the cave gets its name: It stays so cool that ice and snow from the winter months do not melt. The main room is large enough to stand in, but a recent collapse now prevents even experienced cavers from penetrating farther.

After two hikes, we were done for the day. Happy with our initial exploration of the park, we decided to return again to summit Katahdin.

A black bear just below the Knife Edge. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

After that first visit to Baxter State Park, I spent a month poring over maps and trail guides to determine our route up Katahdin and watching the weather forecast for a clear weekend. There are many paths up the mountain, some easier than others. It’s not a technical climb, requiring expertise, but it does require endurance and a fair bit of scrambling over rocks. And because we wanted to traverse the Knife Edge, we had to go on a day when the weather was cooperating with relatively low winds.

We finally found the right weekend in early October — before the park closed to climbing for the winter — and headed out.

Nico and I camped in the park so we could get an early start and planned a loop trail. We began on the Chimney Pond Trail, a moderate 5.3-kilometer rocky path with a gradual incline through a fir-dominated forest. In the dark of the early morning, the rushing sound of the river to our right was amplified. The sunrise behind us slowly peeked through the clouds and lit up the sky. The rocky terrain required constant attention to maintain our footing. After about two hours, we arrived at Chimney Pond, a small circular lake in the basin of a cirque called a tarn.

Scrambling over rocks on the Cathedral Trail, a 2.8-kilometer journey to reach the summit at Baxter Peak. Credit: Nico Ientile.

Maple trees with yellow leaves mixed among evergreens encircled the clear, glassy water — it was still prime leaf-peeping season in the Maine woods — while Katahdin dominated the background. The gorgeous scene notwithstanding, and with the path ahead in mind, I was anxious to keep going.

fter a short amble through the woods, we reached an opening and saw the Cathedral Trail: a steep climb directly up the side of the mountain, which would quickly bring us above treeline. There are less direct and easier routes to the peak, but this one sounded like the most exciting and challenging to us. The trail wastes no time becoming difficult: The first move over a giant boulder required me to stretch and twist my body to clamber over the rock, and it was more of the same for the next three hours — be forewarned, this isn’t a trail for the faint of heart. I occasionally stopped to glimpse the view behind me, which included a steady stream of hikers making their way up the trail. Chimney Pond grew smaller and farther away, additional peaks emerged in the distance, and I saw more lakes and ponds dotting the fiery red, orange and yellow landscape. My legs, meanwhile, grew heavier and heavier.

Baxter State Park as seen from the summit of Katahdin. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

hree hours from the start of the Cathedral Trail, we reached the summit of Katahdin and arrived at what felt like a party. Large groups of people were standing by the sign — some even climbing it — that marks the summit to take photos, having arrived by one of six other paths up the mountain. Thru-hikers were celebrating the end of their four- to five-month walk in the woods with beer (which technically isn’t allowed in the park), and many people, including us, had stopped to eat lunch and drink in the views. In every direction I saw lakes scattered across the landscape and dozens of surrounding peaks. The red and yellow fall foliage broke up the expansive unchanged deep green of the evergreen forest.

The Knife Edge Trail traverses between Baxter and Pamola peaks along the apex of a sharp-crested ridge, or arête. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

fter a respite at Baxter Peak, we packed up for the next leg across the Knife Edge ridge. I was worried that we might not be able to hike the ridge because it’s so exposed. This is not a hike you attempt in rain, high wind, fog, or if bad weather of any sort is looming on the horizon. We were told by rangers to make our decision once we reached the top. If you get to the top and cannot attempt the Knife Edge to complete your loop, you just take one of several trail options back down.

Hikers descend "The Chimney," a 24-meter scramble down a rock wall crevice, and the most challenging part of the Knife Edge Trail. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

ost of the Knife Edge involves hiking over crusty, lichen-covered boulders and fins — rangers and signs remind hikers to stay on the marked path to help preserve the fragile alpine environment. It’s not a particularly daunting physical challenge for someone in reasonably good shape and wearing good shoes, though it can be mentally taxing — and perhaps even frightening for hikers with little experience to such exposure. The hardest part for me was staying focused and constantly watching my footing — I could hardly even look up to enjoy the stunning views. A few sections require scrambling over narrow ledges just a few meters wide with steep cliffs that plummet down hundreds of meters on either side of the trail. At one particularly stomach-churning spot, the trail winds around the side of a granite slab rather than over it.

A panoramic view at the summit of Mount Katahdin. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

hysically, the hardest part of the Knife Edge came during a section of the trail known as “The Chimney” toward the end of the ridge (or the beginning for those hikers making the traverse in the opposite direction). One woman coming the other direction stopped to tell us that she’d cried while crossing it. The Chimney is a notch in the ridge, the traverse of which involves a tricky 24-meter climb straight down over boulders without climbing aids, followed by an equally long, though less challenging, climb back up the other side.

The 5-kilometer Helon Taylor Trail slowly descends below the treeline and brings hikers back to the Roaring Brook Campground. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

Traversing the Knife Edge was exhausting, but the views along the way were spectacular — I was able to steal a few glances along the way — and I felt a huge sense of accomplishment. We even stopped briefly to watch a black bear forage below us on the side of a ledge.

The Knife Edge brought us to Pamola Peak, standing 1,494 meters above sea level and named for the legendary bird spirit in Penobscot mythology. Pamola, the god of thunder, lived on, and protected, Katahdin. He’s described as having the head of a moose, body of a man, and wings and feet of an eagle. The Penobscot people feared and respected Pamola, so hiking the mountain was taboo.

For the next 5.2 kilometers along the Helon Taylor Trail, we descended from above treeline back into the forest. For this portion of the hike, I wished I had brought trekking poles, as repeatedly stepping down over boulders was a bit hard on the knees. Our path down was long and uneventful, but it was our only option to make the trek a loop after traversing the Knife Edge. With so many trails to explore Katahdin, I think next time we’ll pick a different route. Other paths, for instance, offer glimpses of waterfalls and walks along an alpine tableland. Ten hours after we had started that morning, we arrived at the campground, exhausted but exhilarated and ready to relax.

Hiking around Katahdin is quite varied: it can be a peaceful walk in the woods or a scary traverse across a rocky ledge — sometimes both in the same day. Credit: both: Bethany Augliere.

A view of the Knife Edge Trail from Pamola Peak at 1,499 meters. Credit: Bethany Augliere.

For anyone with hiking experience who enjoys adventure in remote locations, I highly recommend Katahdin. There are multiple paths of varying degrees of difficulty, but whichever path you choose, be prepared for a long, challenging day. The payoff, however, includes incredible views of the Maine woods; the chance to see bears, moose and other wildlife; and ample opportunity to stretch your legs in a wild and rocky landscape. It was even named one of the world’s 10 best summit hikes by National Geographic.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.