by Callan Bentley Thursday, October 26, 2017

Goatfell is the highest point on the Isle of Arran. The granitic mountain is also a showpiece of alpine glaciation. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/mille19.

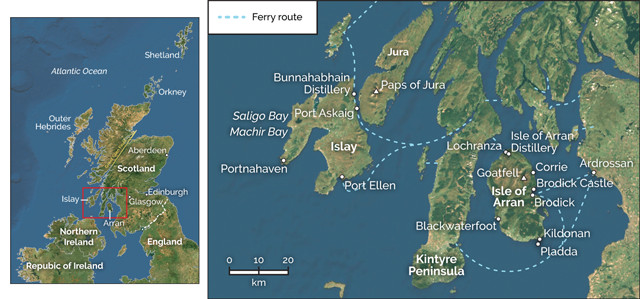

Arran and Islay are two large islands of southwestern Scotland that showcase a suite of interesting rocks and landscapes, and Scotland’s second-finest product (after the geology): single malt whisky. Visiting Arran and Islay together is an enjoyable experience in contrasts. Both islands are sparsely populated, with a few thousand permanent residents each, but amenable to tourists, boasting well-developed infrastructure, including regular ferry service from the mainland. Arran is mountainous, while Islay has relatively subdued topography. Both get a lot of visitors in the summer and feature a wealth of cultural and recreational opportunities, in addition to outcrops that will prove insightful to the geologically minded traveler.

Arran has a breadth of geology that closely mimics that of the Scottish mainland. For this reason it’s been a mainstay field trip destination for Scottish geologists since James Hutton first developed the science here in the late 1700s. Touring Arran, you can really get a sense of the overall geology of the country — and with much less driving.

The first spot that James Hutton contemplated an angular unconformity wasn't at Siccar Point, generally considered the most famous example: It was this small outcrop on the northern shore of Arran. Here, Dalradian metasediments dip steeply off to the left, while younger sedimentary layers dip at a gentle angle off to the right. Credit: Callan Bentley.

“For example, a short distance north of Newton Point in the northern part of Arran, just a pleasant stroll east from the town of Lochranza, there’s an angular unconformity. It was first spotted by Hutton in 1787, prior to the more famous examples at Jedburgh or at Siccar Point (both of which he first visited in 1788). At Lochranza, the unconformity juxtaposes metasedimentary rocks of the Dalradian Supergroup — ancient, slightly cooked, deep-ocean avalanche deposits — against Carboniferous sandstones, maybe 400 million years younger. It’s not especially obvious as a landscape feature, just a little nubbin rising up next to a creek bed, but the different rock units have distinctly different colors and textures. It’s easy to see the thin-layered, landward-dipping foliation in the older metamorphic rocks, and then the contrasting thick blanket of coarse sandstone lying atop them, gently dipping seaward. Between the two units is an ancient erosional surface, along which is missing hundreds of millions of years of geologic time. The subtlety of the outcrop in contrast with the significance of the site from the perspective of historical geology is a delight to contemplate. Surrounded by tufts of soggy grass, you might be tempted to think that Hutton surely sat on this same boulder to ponder the tidy scene, a portal into deep time.

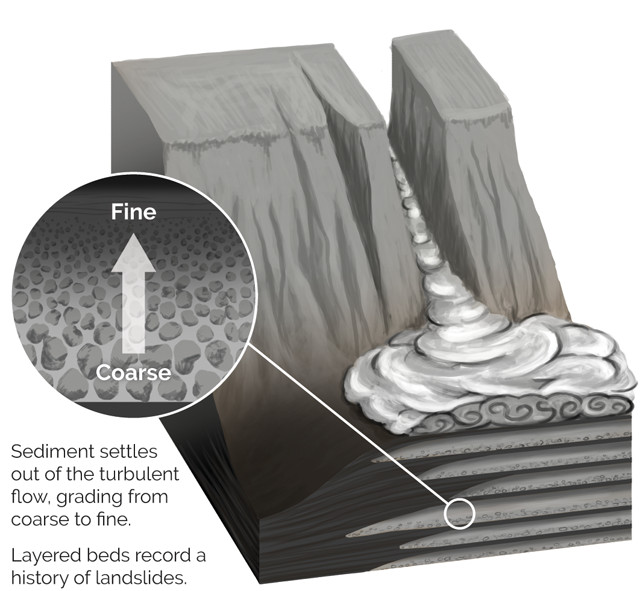

The Dalradian rocks are interesting in their own right, regardless of whether they have anything lying on top of them. They originally formed as deep-sea sedimentary rocks: layers of mud punctuated by gray sand dumped by submarine avalanches called turbidity currents. These violent events are recorded with layers of sand and silt that start off coarse-grained at the bottom and gradually become finer toward the top, a pattern formed by progressively smaller grains slowly settling out of turbid water. Though these layers were later subjected to metamorphism and shearing, the original graded bedding survives in many places — allowing the geological tourist to figure out “which way was up” when the layers were originally laid down.

The geologic map of northern Arran is a concentric set of circles, cored by a big mass of granite. This granite is particularly plain to see in Arran’s highest peaks, including the tallest, Goatfell, which rises to 874 meters. Many visitors to Goatfell enjoy the scramble up the mountain, a hearty 11 kilometers from the trailhead at Brodick Castle on the coast. As you hike, you rise above the treeline into a subalpine ecosystem where the views are spectacular on a clear day, a rarity in Scotland. Regardless of the weather, geo-tourists will enjoy contemplating the granite as you cross its contact with the host rocks and march toward its interior. The granite poked up as a big blob of magma through both the Dalradian metamorphic rocks and their sedimentary blanket, suggesting it’s younger than both of them. Indeed, isotopic dating suggests Goatfell’s granite is only about 58 million years old.

The islands of Arran and Islay can be reached via ferry from mainland Scotland. Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI.

Goatfell is also a showpiece of alpine glaciation. Hikers will gaze with wonder upon arêtes, cirques, horns, moraines and gorgeous U-shaped valleys, all unsullied by trees or forest. It’s a textbook sort of place for contemplating the gouging action of flowing ice, present a mere 18,000 years ago.

Before you leave the area, be sure to check out Brodick Castle (owned by the National Trust for Scotland) at the Goatfell trailhead.

From Goatfell, head back to the coast, to find a suite of wonders near the town of Corrie. A short hike up the hill through midge-infested forest brings you to a set of caves. These caves are cut into Carboniferous-aged limestone, but we’re not here for the speleology. Glance at the cave ceilings and you’ll see knobs and bumps poking out. These are giant brachiopod fossils — each measuring 9 to 12 centimeters across — from the aptly named Gigantoproductus giganteus. The cave walls further reveal them in cross section. Brachiopods are filter-feeders with two shells, superficially resembling big round clams. They were much more common in the Paleozoic than they are today.

Brodick Castle is both the site of the main trailhead to Goatfell, as well as an exquisitely preserved castle in its own right, with many fascinating exhibits inside, and a lovely formal garden outside. Credit: Callan Bentley.

At the Corrie shore, at low tide, one can stroll the rocky coast exploring the local outcrops. There’s much to be seen in this orange sandstone, including the most obvious feature: a bathtub-shaped cavity the size of a car carved into the rock with a recessed stairway leading into it. This was cut two centuries ago by a local doctor named McCredy who used it as a seawater spa for his patients. The declivity fills during each high tide and is then warmed by the sun at low tide. A salty soak here before you continue on your way might refresh you for the rest of your explorations.

Next, embark on a quest to find the contact between the different bodies of sandstone. As you walk the Corrie coast from north to south, you’ll depart fluvial sandstones of Devonian age and cross into windblown Permian sandstones. Can you tell the two apart? Though the color is similar, the two are distinguishable by structures like crossbeds; and a close examination (bring your hand lens) will show clear differences in rounding and sorting. This is another unconformity, though less glaring than the one near Lochranza. If you find it, you can rest assured that your geological chops are strong.

Loch Ranza is an inlet on the northern side of Arran, and home to the community of Lochranza. It features a small herd of deer, an excellent outdoor education center, a distillery and an ancient castle. Credit: Callan Bentley.

As a digestif for your Corrie explorations, search the younger (windblown) sandstone outcrops for a little raised dimple, a few centimeters across. Only accessible at low tide, this unassuming little donut-shaped bump is interpreted as a fulgurite — the fossilized remnant of a lightning strike. It’s the top of a tube of fused sand grains, annealed in an instant during the Permian when lightning struck the sand dunes. The sintered rock weathers more slowly than the surrounding sandstone.

Further ambling along the Corrie coast will reveal Paleogene-aged basalt dikes that have intruded into the sedimentary rock. A better place to view these features, however, is at Blackwaterfoot Beach, so load your gear back into your car (or onto your bicycle) and cross the island to the southwest coast. From the beach parking area, walk north along the beach. The sandstone at Blackwaterfoot has been almost completely etched away by erosion. It is covered in most places by sand, and only the dikes poke out above the beach. So, dodge the sunbathers (if there are any; this is Scotland after all!) and walk toward the distant rocky lines that project into the sea.

A fulgurite is a "fossilized lightning bolt." When this sandstone was still windblown sand piled up in dunes, lightning struck it and fused the grains together in a tubular structure, the top of which crops out here on the coast of Arran, at Corrie. Credit: Callan Bentley.

Each dike represents an injection of magma into a crack in the Triassic sandstones and shales, and as they are all of about the same age, the dikes are collectively dubbed a swarm. When the basalt was injected, the molten rock heated the surrounding sedimentary bedrock, baking it and creating a zone of contact metamorphism — an effect that fades with increasing distance away from the margin of the dike. The edge of the dike itself also records this loss of heat, with distinctly smaller grain sizes forming the so-called chilled margin. By contrast, the center of the dike stayed hot and gooey for longer, and hosts bigger, better-formed crystals as a result of its more prolonged cooling.

Gigantoproductus giganteus — up to 12-centimeter-long brachiopods — can be seen in the caves above Corrie. Credit: Callan Bentley.

At Blackwaterfoot, the dike swarm shows a mix of gray and white crystals, some large and some too small to be seen, a texture that geologists call porphyritic. This texture reveals that the Blackwaterfoot magma actually began slowly cooling farther underground before it was injected into the cracked sandstones. During this slow cooling, the big crystals began forming, and then when the magma intruded into the cracks, it cooled further at a faster rate, producing the smaller matrix crystals.

At the end of the beach, a dramatic cliff looms. This is the Drumadoon Intrusion. It’s the same sort of rock that makes up the dikes along the beach, but rather than basalt cutting vertically across the sedimentary layering of the New Red Sandstone, the Drumadoon formed when magma squeezed between sedimentary layers. This popped a roof of sedimentary strata above it, like a cat shimmying under the sheet of a freshly made bed. This sill of magma cooled and solidified, forming vertical columns that lend an imposing, imperial feel to the massive cliff. Seabirds roost atop them: a nest with a view.

A basaltic dike intrudes the New Red Sandstone at Kildonan, on the south of Arran. Note how the sedimentary rock immediately adjacent to the dike has been both bleached and "baked" and stands up to weathering better as metamorphic hornfels. Credit: both: Callan Bentley.

A short hike beyond Drumadoon grants the opportunity to explore the vegetation-covered cliffs. We’re beyond the intrusion here, and back into Mesozoic mudrocks. If you’re lucky, you might spot the large fossil reptile tracks that are visible in some places. Once your search concludes, retrace your steps across Blackwaterfoot Beach to your car and head south toward Kildonan.

The coastal exposures at Kildonan, on Arran’s south coast, show more of the dikes, with exquisitely preserved haloes of contact metamorphism surrounding the intrusions. The dikes crop out there as wall-like features because the basalt weathers more slowly than the relatively soft sandstone and shale that it cuts through. The dikes here trend north-south, consistent with the radial pattern that characterizes much of Arran. They seem to point offshore at the small island called Pladda, which itself is capped by a sill of the same igneous rock, like a small offshore Drumadoon.

There’s less beach sand at Kildonan compared to Blackwaterfoot, offering a better opportunity to examine the host rocks, which are also of Triassic age. The New Red Sandstone here shows beautiful sedimentary structures, including some excellent dessication cracks in muddy layers. When a deposit of mud dries out, it shrinks a bit. The shrinkage is greater than the cohesive strength of the mud, so it cracks. These cracks link up to make beautiful patterns and polygons that speak to arid conditions of the geological past. The cracks are widest at the top, and narrow as they penetrate downward into the still-moist mud. Later deposits of white sand filled these cracks in places, resulting in a sand layer with numerous dagger-like projections poking down into the red mudrock below. According to my 4-year-old, it looks like a toothy monster’s mouth.

Columnar jointing is an obvious feature of the Drumadoon Sill, near Blackwaterfoot. Nearby beaches show dikes that shot off from the main intrusion. The local host rocks feature large reptile footprints, and the cracks between the columns host nesting seabirds. Credit: Callan Bentley.

Four-year-olds also like castles, and Arran has a few to offer. Brodick Castle, on the east coast of Arran, and Lochranza Castle, which sits on a wedge of land poking into Loch Ranza in the north of the island, offer an interesting comparison. Constructed in the early 1500s, Brodick Castle is quite fancy, full of art and historic furniture, and surrounded by formal gardens. Entry will cost you £13 per person. In contrast, Lochranza Castle dates to the 1200s and is a ruin. It is open and free to the public, however, and makes for a good game of hide-and-seek.

So now you’ve got a full sense of the geology of this special isle, and a sense of its historical offerings. Are you hungry? Thirsty? Hooked and Cooked is a fish and chips joint in Brodick with terrific, inexpensive food that’s piping hot and hearty enough to drive away the Scottish rain. Speaking of things that warm you up from the inside, I also recommend the Isle of Arran Distillery in Lochranza. It’s the sole whisky distillery on Arran, and offers a unique datum to compare with offerings from Islay.

An outcrop of contact-metamorphosed New Red Sandstone at Kildonan shows cross sections of white sand-filled dessication cracks in red mudstone. The mud cracks project into the mud, narrowing from the surface downward. This outcrop is adjacent to a prominent wall-like dike intruded into the sedimentary rocks. Credit: Callan Bentley.

Islay lies west of Arran, on the other side of the Kintyre Peninsula. As such, it’s officially part of the Inner Hebrides, and it has been historically dubbed “Queen” of the island group. Why crown this island a monarch? Many would suspect it’s the whisky, as Islay draws tourists from across the planet to sample products from its eight active distilleries. But I would argue that Islay has just as strong a claim to royalty on the basis of its rocks.

Islay’s rocks haver, just like the island’s intensely peaty malt whiskys. If we turn to the Dalradian metamorphics, we don’t find anything that looks quite like the metamorphosed turbidites on Arran. Instead, there are gleaming white quartzites, a signature of nearshore or beach sand from the Neoproterozoic Era that has been slightly metamorphosed. Their finest expression is across the Sound of Islay on the neighboring island of Jura. There, the quartzite crops out as a trio of impressive peaks, the Paps of Jura, each about 750 meters tall. They are the tallest mountains around, and have a habit of lifting the passing atmosphere up over their bulk, triggering the formation of hat-like clouds over them. This orographic effect requires perspective to appreciate: You could try from Barnhill, on Jura’s northern tip, which is what George Orwell did when he was writing “1984,” but you’d do just as well to stay on Islay and gaze eastward in the late afternoon.

Lochranza Castle is open to visitors; the author's family enjoyed playing hide-and-seek inside. Credit: both: Callan Bentley.

While Islay might ng mountains like Jura does, it does have a rock that can’t be found anywhere else: the Port Askaig Tillite. This extraordinary rock is petrified glacial debris (till) from the Snowball Earth glaciations, specifically the Sturtian Ice Age, which happened about 650 million years ago. It is a very poorly sorted sedimentary deposit with great big cobbles and boulders of exotic clasts (pink granite is the most photogenic) surrounded by gray grit, sand and mud. Ice sheets during these Snowball Earth glaciations are thought to have reached all the way to the equator, indicating a radically different climate on our planet during the Neoproterozoic. Around the world, glacial deposits from the Snowball Earth episodes are typically overlain by cap carbonate deposits (limestones and dolostones), and that’s true in Islay as well.

The Paps of Jura are prominent mountains of Proterozoic quartzite that are visible from eastern Islay. Credit: Callan Bentley.

Near the Bunnahabhain Distillery are beautiful outcrops of the Bonahaven Dolomite. Prowling the shore here, visitors are rewarded with stromatolites, mudcracks and plenty of other sedimentary structures preserved in these ancient dolostones. The Bonahaven doesn’t look like a typical Snowball Earth cap carbonate on this count — they don’t usually preserve such structures — but the differences are part of the appeal of getting to know it. As at Arran, there are dikes of igneous rock cutting across the coastal exposures. And access is via the Bunnahabhain Distillery, making for an enjoyable post-excursion tipple.

The Port Askaig Tillite hosts a profusion of dropstones from the Snowball Earth episode of glaciation during the Neoproterozoic. Credit: Callan Bentley.

During Snowball Earth, glaciers scraped the land surface, picking up big chunks of rock that were deposited at sea along with a surrounding matrix of much finer material. Credit: Callan Bentley.

Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

In the aftermath of the Snowball Earth glaciations, tremendous quantities of carbonate were deposited. At Bonahaven ("Bunnahabhain"), stromatolites like these grace the carbonate succession. Credit: Callan Bentley.

On the west coast of the island, you’ll find more turbidites. In this case, the ancient submarine landslides belong to the Colonsay Group, named for the island just north of Islay (the site of John McPhee’s 1970 book “The Crofter and the Laird”). These strata have been correlated with the oldest of the Dalradian groups of metasedimentary rock, in contrast to the turbidites we observed in northern Arran, which are relatively young but also relatively altered by mountain building. Those in western Islay show very little evidence of metamorphism, but do show well-developed cleavage and oodles of gorgeous folds. One fine place to examine these rocks is at Machir Bay, where the Kilchoman Phyllite crops out, replete with many, many folds and crosscut by a swarm of dikes. A word of caution: Exploring these rugged coastal outcrops leads you past tidepools full of rotting seaweed. The noxious fumes coming out of these pools could strip paint, so once you start getting whiffs of the rot, choose a new route.

A more salubrious location is found at Saligo Bay, where the Smaull Graywacke crops out. I’m a bit of a connoisseur of turbidites, and I must say that the examples on display at Saligo Bay are among the finest I’ve seen anywhere. The grading is exquisite and unambiguous, starting off with coarse dirty sandstone then fining and fining and fining upward until there is only black shale. Then the whole thing repeats. As with the neighboring phyllite, these turbidites are much improved by having accrued a little deformation. Their folding and cleavage is explicit, and variably developed across the different strata — the graywacke resists squeezing more, while the former shale has been transformed to a slate. A big diabase dike slams through all those, rising like the Great Wall of China above the more easily eroded outcrops. I love outcrops like this, where there are multiple chapters of the local story on display, and where each overprints those before it in a rocky palimpsest. Meanwhile, the fog drifts in and the waves crash, making this a place of terrific beauty.

Crashing waves are also a theme at Portnahaven, in southwestern Islay, where a wave-powered generator facility lies abandoned and rusting, the surging waters still slapping it with terrific force. If you visit this site, be very careful: Rogue waves have claimed more than one life here, rising up unexpectedly and focused to powerful dimensions by the shape of the rocky coast. I’d argue, however, that it’s still worth a bit of risk to check out the site, as it hosts wave-scoured outcrops of mylonite, the name given to smeared-out rocks found along hot, deep faults. The rocks smeared out here were a complicated lot of igneous origin: the Rhinns Complex. These are the oldest rocks in either Islay or Arran, and are thought to have intruded as magma 1.78 billion years ago, with metamorphism and deformation occurring shortly thereafter.

Great examples of graded bedding may be observed on the beach at Saligo Bay, including this stellar outcrop showing three graded beds. Turbidites like these piled up in abyssal fans at the foot of submarine canyons, one submarine landslide at a time. Each is sandy (light-colored) at the base and grades upward into black shale. Credit: Callan Bentley.

Hedgehogs are among the local wildlife on Arran and Islay. Credit: Callan Bentley.

If you’re lucky enough to visit Islay for its geology, I recommend the book “A Walking Guide to the Geology of Islay,” by David Webster, Roger Anderton and Alasdair Skelton. While I was there, I happened to meet David Webster, and (over whisky) he gave great advice for accessing the most interesting rocks. The book is structured around walks you can take, complete with detailed maps that are perfect for a geological traveler. Furthermore, the book is unique among geology guides by offering suggested whisky pairings for each field trip in the book (all from Islay, naturally).

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.