by Kathrina Szymborski Wednesday, June 6, 2018

Any minute now a giant sandworm will burst out of the ground and devour me, I thought as I collapsed on the sand. Just like in Frank Herbert’s book, “Dune,” about an alien desert planet.

I had just climbed Dune 45, the world’s most photographed dune, in Namib-Naukluft National Park, Namibia. The sand slipped out from under my feet with each step I took up the 170-meter-high dune. The wind, tame in the valley below, hurled sharp grains of sand against my face. The sun seared my skin. I suddenly understood why the desert Fremen people in “Dune” only moved at night.

Below me in the Tsauchab River Valley, my father waved enthusiastically. This trip to Namibia was his 70th birthday present. He was content to watch me climb from below, keeping an eye out for springbok gazelles grazing on the grasses at the dune’s base. He hadn’t made it healthily to age 70, he told me, by wasting his energy scrambling up mounds of burning sand.

The dunes near Sossusvlei were but one of the spectacular geological sites we would explore on our journey through Namibia.

Namibia’s Many Meteorites

Our survey of Namibia’s geological treasures started as soon as we deplaned in Windhoek, Namibia’s capital. Windhoek is a quiet, quaint and clean city in the center of the country. Its center square harbors something exceptional: 33 meteorites, ranging in weight from 195 to 555 kilograms, perched artfully atop display stands of varying heights. These are the Gibeon Meteorites, which, according to radiometric dating estimates, are about 4 billion years old. They are thought to have collided with Earth between 220 million and 200 million years ago, as part of the largest known shower of extraterrestrial bodies ever to do so. They are positively otherworldly.

The mostly iron meteorites exhibit finely interleaved bands of kamacite and taenite, following the Widmanstätten pattern unique to metal bodies formed in space. The meteorites also contain nickel, cobalt, phosphorus, carbon, sulfur, chromium, zinc, gallium, germanium and iridium. A total of 120 pieces have been found with almost identical composition. They are thought to have initially been part of the same 14-metric-ton body. But the Gibeon Meteorites are not the most remarkable extraterrestrial attraction in Namibia. On an old farm near Grootfontein, in northeastern Namibia, lies the Hoba Meteorite. The Hoba is the largest-known metal meteorite and heaviest naturally occurring piece of iron in the world (mixed with nickel and traces of cobalt). Because of its mass — almost 55 metric tons — the Hoba has never been moved from the place where it landed about 80,000 years ago. Unlike most meteorites, it is flat on both major surfaces. Some scientists suggest that this unusual shape caused it to skip across the top of the atmosphere like a flat stone skipping on water.

The Hoba is a member of a very rare class of iron meteorites called Ataxites. Iron meteorite falls are rare compared to stony meteorites; they comprise less than 6 percent of witnessed falls. Ataxites, a subset of iron meteorites, are even rarer. No observed meteorite falls have been Ataxite. Although Ataxites seem to have no discernible internal structure, under a microscope, they reveal extremely fine Widmanstätten patterning.

Visiting the Hoba also gave us the opportunity to explore the nearby Kavango region. The Kavango people are known for their exquisite woodworking. We weren’t disappointed. An hour outside Grootfontein, we met a woman selling beautiful hand-carved elephants by the side of the road. She studied me as I studied her artwork. Finally, determining that she and I were roughly the same size, she proposed that I give her the dress I was wearing in exchange for one of her carvings. It seemed like a good deal. The elephant is now the centerpiece of my tiny apartment in New York City.

Etosha National Park

After admiring the woodcarvings in the Kavango region, we headed to the nearby Etosha National Park to see the creatures that had inspired the carvings.

Etosha boasts as its centerpiece a vast salt pan — the remnant of an ancient lake — spanning almost 4,600 square kilometers, or 21 percent of the park. It is part of the Kalahari Basin, the floor of which was formed about a billion years ago. The Kunene River once flowed from the Angolan highlands into the lake before tectonic plate movements shifted the Kunene’s course, causing the river to bypass the lake and allowing it to dry up.

During the dry season, the pan’s minerals enrich the downwind soil. During the wet season, the pan floods, and the resulting growth of blue-green algae attracts thousands of flamingos. Year-round, the surrounding vegetation and perennial springs sustain almost 340 bird species and 150 mammal and reptile species, including rare animals like the black rhinoceros and the black-faced impala.

The morning of our arrival at Etosha, we set up camp in the Okaukuejo Rest Camp. After a week of sleeping in the truck bed on the side of the road — the vast distances between landmarks in Namibia made it hard to plan lodging in advance — I was looking forward to spending a night in a tent.

Before I had secured the first stake in the soil, I saw something moving out of the corner of my eye. Only 20 meters away, two elephants lumbered steadily past our camp, toward the nearby waterhole.

“Elephants!” I yelled. “Dad! Come on!” I took off running down the path toward the waterhole viewing area. Etosha’s three public campgrounds each have flood-lit waterholes where visitors can sit quietly and watch animals drink throughout the day and night. There are dozens more waterholes scattered throughout the park, drawing the animals out of the bush during the dry season.

After the elephants had quenched their thirst and disappeared into the surrounding mopane woodland, we made our way toward the salt pan. It was shimmering in the late morning sun, a hazy kaleidoscope of green, silver and pink stretching as far as we could see. Giraffes, springbok, zebra, ostrich, gemsbok antelope, and other animals sauntered over the flat, cracked surface, paying each other no mind.

We returned to our campsite as the sun was setting, tired and with a gritty layer of salt coating our skin. I was just beginning to prepare a meal of bread, apples and peanut butter when a Namibian couple staying in the neighboring campsite approached me. They had a couple extra steaks, they explained, and they hoped my father and I would join them for dinner. That night, under a waxing crescent moon, we toasted to my father’s 70 years with our new friends. We chased away jackals that tried to steal our food, watched two lionesses make a failed attempt to take down a giraffe at the waterhole, and then slept soundly until dawn.

Namib-Naukluft National Park and Sossusvlei Pan

Although we didn’t want to leave Etosha, there was much left to see in Namibia. From Etosha we made our way about 700 kilometers south to Namib-Naukluft National Park, where I climbed Dune 45.

Dune 45 sits at the 45-kilometer mark along the Namib-Naukluft National Park’s main road, jutting out of a valley of pale yellow grass. The massive mound hints at what’s to come: A sand sea of red, orange and pink 300-meter-tall dunes stretching past the horizon — among the tallest in the world. The brilliant hues are a result of oxidation of the sand’s high iron concentrations. The older the dune, the more intense its color. Ninety to 95 percent of the sand in the area is silica. In some places, feldspar, magnetite and ilmenite create black stripes against the orange. In others, garnet splashes maroon into the glowing dune slopes. Some dunes are tinged light gray along their bases, the result of limestone silt carried in by the Tsauchab River.

Namib-Naukluft National Park is the focal point of the Namib Desert for tourists. The 55-million-year-old Namib stretches for more than 2,000 kilometers up the South African and Namibian coasts into Angola, and 200 kilometers eastward from the Atlantic Ocean. It’s the only true desert in southern Africa; annual precipitation ranges from 2 millimeters in the most arid regions to 200 millimeters at the desert’s easternmost edge.

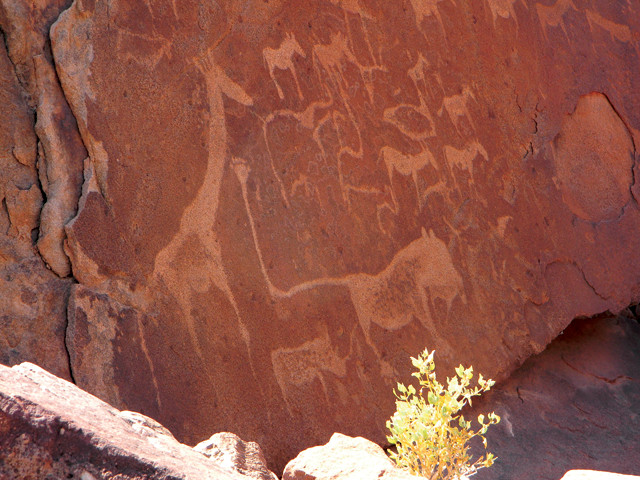

Some of the 5,000-year-old petroglyphs near Twyfelfontein; the site was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2007. Credit: Kathrina Szymborski

After my brief respite at the summit of Dune 45 contemplating sandworms and the Fremen, I ran back down the side so we could resume our journey. We had only 20 kilometers to go to Sossusvlei, a salt and clay pan around which the park’s tallest dunes tower. For as long as I could remember, my father had talked about visiting Sossusvlei.

The Sossusvlei pan, an endorheic drainage basin for the Tsauchab River, is situated about 65 kilometers down the main park road. Water rarely reaches Sossusvlei; the Tsauchab riverbed is normally dry. In years of exceptional rainfall in the catchment area of the Naukluft Mountains, however, the 100-kilometer-long Tsauchab can become a furious waterway in a matter of hours. The risk of flash floods is particularly high in the narrow, kilometer-long, 30-meter-deep Sesriem Canyon — a gorge cut out of sandstone and limestone over the last 30 million years. In wet years, most recently 2008, the usually barren pan becomes an oasis.

Other ancient pans lie to the south and west of Sossusvlei. These haven’t seen water for hundreds of years. Most eerie is Deadvlei, a clay pan formed more than 900 years ago when flooding of the Tsauchab River created temporary pools around Sossusvlei. Camel thorn trees took root in the sudden abundance of water. Then the pools dried and drought set in. Sand dunes crept toward the pan, blocking the Tsauchab’s access to the area and killing the trees. Today, the desiccated black husks of the 900-year-old trees dot Deadvlei, preserved by the extreme lack of moisture. Their twisted shadows provide welcome shade in the pale, cracked clay of the old pan, and slight protection from the desert winds.

Multidirectional winds constantly re-contour the Namib-Naukluft dunes’ crests, slopes and slip faces. Most of the dunes accessible to visitors in the park are star dunes, or multiridged, radially symmetrical dunes with arms radiating from a high central mound. Sand is deposited on the windward slope of each arm; when the slope reaches 32 degrees, grains of sand slide down the slip face. The constant movement of sand from the windward sides to the slip faces maintains each dune’s equilibrium, allowing it to move and shift as a whole instead of dispersing.

Star dunes are the most stable of all dunes. This stability is reinforced by a small amount of moisture retention on the windward side of the dune. The combination of stability and moisture allows grasses to flourish on the windward slopes of the Namib-Naukluft dunes. Meanwhile, the soft, dry sand on the slip face is better aerated than the sand of the dune slope. As a result, many reptiles, small mammals and insects make their homes on the slip face.

Otherworldly Landscapes and Other Geologic Wonders

Credit: AGI/NASA

From Sossusvlei, it was less than 300 kilometers back to Windhoek. As my father slept on our last night in Namibia, I started to chronicle all the things we’d seen. Not a day passed during our three-week trip that we didn’t stumble upon an unexpected geological curiosity.

I thought about the Moon Landscape, an undulating panorama near Swakopmund that was once a high mountain range, formed about 500 million to 460 million years ago by a granite intrusion. It lived up to its name.

I pictured the 280-million-year-old petrified forest we passed on our way to the town of Khorixas and the 5,000-year-old petroglyphs we saw close to Twyfelfontein that featured animals and maps of water sources. In the margins of my notebook, I sketched the tracks left near the town of Omaruru by Ceratosaurus and Syntarsus, dinosaurs that lived about 200 million to 190 million years ago.

Namibia’s natural wonders are too vast to take in fully in only three weeks. There were caves; flat-topped mountains; and diamond, uranium, gold, zinc and other mines that we hadn’t had time to visit. There was Fish River Canyon, one of the largest in the world. The Ai-Ais hot springs flow from beneath the peaks at the southern end, its 60-degree Celsius waters rich in chloride, fluoride and sulfur — a relaxing and naturally therapeutic dip.

I closed my journal and gazed up at the Southern Cross, drawing an arc with my finger to connect the dots. The stars reminded me of the salt crystals we’d passed on our drive from Walvis Bay to Swakopmund. Unmanned wooden planks displaying baseball-sized salt crystals lined the road. These crystals were for sale, and payment was on the honor system. Between 180,000 and 400,000 tons of salt are harvested there each year.

Soon I would be back in New York, looking at the Big Dipper instead of the Southern Cross. The only salt I’d see lining the roads would be there to melt the ice in the winter. I suddenly wished I’d bought a bunch of those salt crystals.

Next time.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.