by Terri Cook and Lon Abbott Thursday, January 26, 2017

The Roman ruins of Masada offer a panoramic sunrise view over the Dead Sea Rift. Credit: Lon Abbott & Terri Cook.

We were raised in a culture strongly influenced by biblical stories. Tales like Saul’s pursuit of David through the Judean wilderness, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, and the fate of Lot’s wife are touchstones that have shaped our society’s moral and ethical norms and echo through Western literature. The geology of the Dead Sea Rift, where those tales unfolded, is integral to their content.

Being both geologists and history buffs, we were eager to immerse ourselves in the region’s impressive geology and witness its role in those civilization-shaping stories, not to mention visit the world’s lowest point on dry land and soak in the Dead Sea’s famously therapeutic waters.

At 429 meters below sea level, the shore of the Dead Sea is the planet’s lowest point on land. Despite its name, the Dead Sea is actually a lake, and because there is no natural outlet for its waters, it is hypersaline, with dissolved mineral concentrations nine times greater than the ocean. Although it is too salty for life to survive in it, the Dead Sea has become a popular tourist retreat thanks to the therapeutic value of its water and mud and its proximity to several additional attractions.

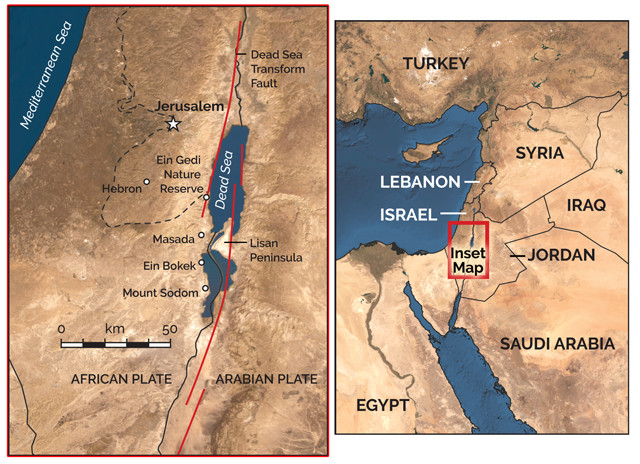

The Dead Sea Transform Fault separates the African Plate from the Arabian Plate and runs through the center of the Dead Sea. Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI.

The Dead Sea Transform Fault, a strike-slip fault that separates the African Plate from the Arabian Plate, runs right through the middle of the Dead Sea. This transform is a continuation of the same plate boundary that forms both the Red Sea and East African rifts, but the plate dynamics change substantially from south to north, with the amount of strike-slip motion along the boundary increasing to the north. In East Africa, the plates separate without significant horizontal sliding, while in the Red Sea Rift, there is significant strike-slip motion, though plate separation still dominates, resulting in the formation of new oceanic crust. North of the Red Sea, the dominant motion becomes strike-slip along the Dead Sea Transform, but enough stretching also occurs here to thin the continental crust. This stretching has produced a classic rift landscape in which the Dead Sea Rift (which is called a graben) has been dropped down along normal faults while the blocks to both the east and west have been flexed upward to form flanking plateaus (called horsts).

Immediately west of the Dead Sea, another must-see attraction is the ancient fortress of Masada, a UNESCO World Heritage site built by Herod the Great from 37 to 31 B.C. atop a 150,000-square-meter, diamond-shaped mesa that crowns an especially dramatic horst. Although the horst rises a mere 58 meters above sea level, due to the rift valley’s low elevation, it soars nearly 500 meters above the Dead Sea. The mesa top bristles with 100-meter-high cliffs breached by only two hiking trails, the Roman Ramp and the switchbacking Snake Path.

Herod's palace at Masada was adorned with intricate mosaics. Credit: Lon Abbott & Terri Cook.

“The climb up the Roman Ramp is a moderately steep but short 15-minute hike that utilizes a siege ramp built by the Romans in A.D. 73. The more challenging Snake Path ascends the mesa from the Dead Sea Basin to the east, climbing 270 meters and weaving back and forth between the tall cliffs that guard the summit. To beat the heat and enjoy the commanding view of the sea at sunrise, we embraced the tradition of a pre-dawn ascent. Non-hikers can reach the summit via cable car, which begins operating at 8 a.m.”

“Once on top, visitors can explore Roman ruins in a most unusual setting. According to the Roman historian Josephus, Herod, the Roman king of Judea, constructed the fortress and its two palaces as a refuge in case of revolt. During the first Jewish-Roman war in A.D. 66 to 73, a group of Jewish zealots overran the complex and held it for seven years. In response, the Romans patiently constructed their siege ramp atop a small bedrock spur that links Masada to the Judean Plateau. Once completed, they rolled a battering ram up it to breach the fortress walls. According to Josephus, the zealots all committed suicide to avoid capture. Although archaeological evidence doesn’t support this account, the zealots’ defiance became a symbol of Jewish resistance. Some modern Israeli soldiers are sworn in at Masada, where they traditionally chant that “Masada will never fall again.”

We were impressed by Masada’s dramatic setting and historic ruins, but we were equally excited to see the sedimentary evidence for ancient earthquakes recorded in a network of steep ephemeral gullies, called arroyos, at its base — an aspect of Masada most tourists miss. These “seismites” consist of disturbed layers within the otherwise rhythmically laminated Lisan Formation.

This formation was deposited between 70,000 and 12,000 years ago in Lake Lisan, a larger version of the Dead Sea whose maximum surface elevation was 160 meters below sea level during the last ice age. The formation consists of a thick series of varves: pairs of millimeter-thick layers, one consisting of aragonite and the other of sedimentary detritus, which form each year. Similar varves accumulate on the floor of the Dead Sea today. During winter storms, the Jordan River delivers detritus to the sea through normally dry arroyos, which is then overlain by aragonite crystallized from the hypersaline water during intense summertime evaporation.

The region dried out as global glaciers retreated, causing the Dead Sea’s surface elevation to drop 240 meters and reach a stable Holocene elevation of about 400 meters below sea level. That stability has recently been disturbed by water diversion projects; since 1930, the Dead Sea’s surface height has dropped 39 meters, reducing its area by 30 percent and contributing to the formation of 5,500 sinkholes. Despite the sea being, at 304 meters, the deepest salt lake on Earth, scientists calculate that at the present rate of decline it will disappear by 2050.

“The area’s drainage network has responded to the post-glacial drop in the lake level by cutting the 50- to 150-meter-wide and 40-meter-deep arroyos that expose the Lisan Formation’s internal structure. While wandering through the arroyos, we marveled at the numerous horizons containing fractured and folded beds that break up the monotony of the flat varves. Each such horizon records sediment liquefaction during an ancient earthquake. Scientists have used these disturbed beds to construct a 50,000-year earthquake record for the region, the longest continuous earthquake record anywhere on Earth.

David Falls is named for the biblical King of Israel. Credit: Lon Abbott & Terri Cook.

Although the Old Testament makes no mention of Masada, many biblical scholars suspect that a pre-Herodian, mesa-top fortress was one of the places where David hid from Saul, Israel’s first king. According to the Bible, Saul grew suspicious that David, whose popularity soared after he slew Goliath, would usurp the kingdom. David fled to the Judean wilderness west of the Dead Sea, where Saul pursued him for years. The lush oasis of Ein Gedi, just 21 kilometers north of Masada, figures prominently in this biblical tale because it was there that David cut a piece of Saul’s robe instead of killing him. This act led to reconciliation between the two, with David retiring to a nearby mountain fortress (possibly Masada) shortly before becoming the second king of Israel.

Today, the Ein Gedi Nature Reserve protects two narrow canyons that slice through the Judean Plateau en route to the Dead Sea Graben. These canyons were carved by spring-fed streams flowing along a fault that runs almost perpendicular to the main, graben-forming faults. Amid a rugged and desolate landscape pockmarked with caves, these streams tumble down beautiful waterfalls and create a verdant oasis. In addition to sheltering David, this oasis features in a love poem from the Old Testament’s Song of Songs that celebrates Ein Gedi vineyards. During the easy, one-hour stroll to David Falls, our family enjoyed splashing in the many swimming holes, admiring the lush vegetation, and searching for the wildlife, including the hyrax and the majestic Nubian ibex, that depend upon these life-giving waters.

About 30 kilometers south of Masada, Mount Sodom, an 11-kilometer-long salt dome that shares its name with the biblical city of Sodom, rises 220 meters above the Dead Sea. One of the five “Cities of the Plain,” the city of Sodom was the scene of one of the Bible’s most indelible stories of morality: Displeased by the wicked ways of the city’s inhabitants, God destroyed Sodom and the nearby town of Gomorrah using fire and brimstone.

Salt layers were contorted as they rose 4 kilometers to Earth's surface in the Mount Sodom salt dome. Credit: Lon Abbott & Terri Cook.

No one knows for sure if these cities actually existed, but many biblical scholars argue that they were located east of Mount Sodom and were destroyed by an earthquake and an ensuing fire. Additional evidence of their existence has come from Jordan’s Lisan Peninsula on the opposite side of the Dead Sea, where archaeologists have discovered the remains of two Bronze Age cities, built on a major fault, that appear to have been destroyed by fire.

These cities likely thrived on the salt and asphalt trade discussed by historians such as Strabo and Pliny. During antiquity, the southern Dead Sea was famous for its sulfur-rich asphalt, which was highly prized for its use in mummification. Scientists who have chemically analyzed the asphalt have concluded that it is brought up from depth during earthquakes, most likely accompanied by highly flammable hydrogen sulfide gas. Brimstone is another name for sulfur, and scholars speculate that earthquake-released hydrogen sulfide caught fire, engulfing the cities in flames. According to the Bible, Abraham, watching from the city of Hebron, observed acrid smoke rising above the plain — the kind of smoke that would be produced by burning asphalt. The Dead Sea paleoseismic record identifies a candidate earthquake that occurred about 2100 B.C.

A detached spire on Mount Sodom is named for Lot's Wife, who in the biblical tale was turned into a pillar of salt. Credit: Lon Abbott & Terri Cook.

The Bible further describes how townspeople fleeing the destruction died after falling into deep pits. The 68-cubic-kilometer Sodom salt dome and its much larger (780-cubic-kilometer) neighbor on the Lisan Peninsula are riddled with dissolution caves that could be those biblical pits. Both balloon-shaped domes consist of salt deposited during evaporation of an arm of the Mediterranean Sea that flooded the rift valley 2 million to 5 million years ago. After several kilometers of younger sediment accumulated atop this salt, its low density made it unstable and caused the salt to flow upward along the graben faults, forming the two domes, which continue to rise as fast as 7 millimeters per year.

Angels, according to the Bible, warned Lot and his family to escape the city before Sodom’s destruction, instructing them not to look back at the burning town. When Lot’s wife flouted God’s command, though, she immediately turned to salt. Today, where the main road skirts Mount Sodom, there are good views of the freestanding salt pillar known as Lot’s Wife.

The summit of Mount Sodom offers a panoramic view of the southern Dead Sea. One of the two hiking routes along the mount is called the Fishes Trail, a reference to the many fossilized fish entombed in the salt. Because the many salt caves make off-trail hiking hazardous, it’s important to stick to the main trail.

We wrapped up our Dead Sea travels with a relaxing, therapeutic soak in its briny waters. Due to the sea’s steadily dropping water level, all the beaches on the main shores have been closed. But the Dead Sea Works, one of the world’s largest producers of evaporite minerals, pumps water from the sea to its evaporation pans at Ein Bokek, where the shoreline is crowded with two public beaches and numerous private facilities.

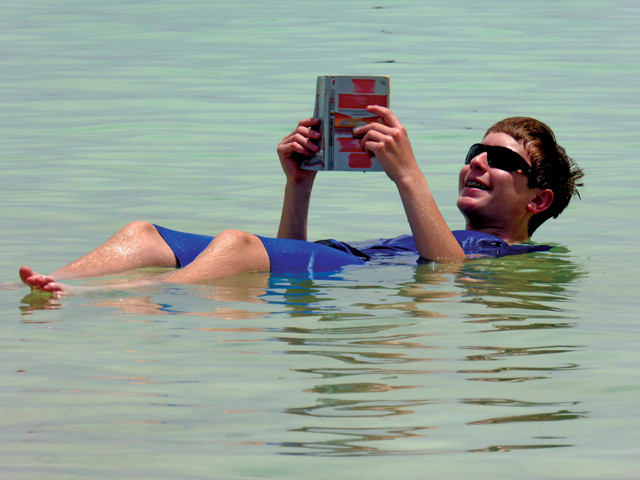

High salinity makes for easy floating in the Dead Sea at Ein Bokek. Credit: Lon Abbott & Terri Cook.

As we waded into the sea, we marveled at how every pebble was coated in salt precipitated from the saturated water. The high density of the seawater, a product of the 34 percent salinity, imparts incredible buoyancy that provides a strange experience for bathers: Our bodies hovered at the surface as if we were lying on inflatable floats, and repeatedly bounced back up if we tried to dunk below the waves. We reveled in the novelty of spending a relaxing afternoon catching up on reading while bobbing in the Dead Sea’s soothing waters.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.