by Terri Cook and Lon Abbott Thursday, October 22, 2015

The soul of Cyprus lies in the Troödos Mountains — a rare, intact sliver of ancient oceanic crust — and in the beautiful mountain villages dotting their slopes. Credit: ©Shutterstock.com/Konstantin Kopachinsky.

The eastern Mediterranean island of Cyprus played a pivotal role in the development of plate tectonic theory. Thus, when planning a recent eastern Mediterranean trip, we, as geologists, deemed it almost blasphemous not to include a visit to Cyprus on our itinerary. We had to see for ourselves the rocks that were so instrumental to the development of this geological paradigm. When our research revealed that Cyprus also hosts famous archaeological sites dating from Neolithic to Roman times, Byzantine churches listed as a World Heritage site, classic Mediterranean cuisine and wine, and gorgeous beaches, the decision to visit Cyprus was an easy one.

Cyprus, the third-largest island in the Mediterranean, has been a battleground between Turkey and Greece for centuries. The isle is currently divided into the southern Republic of Cyprus, which is more closely linked with Greece, and the Turkish-controlled territory called the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. The United Nations patrols a buffer zone between them. Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI.

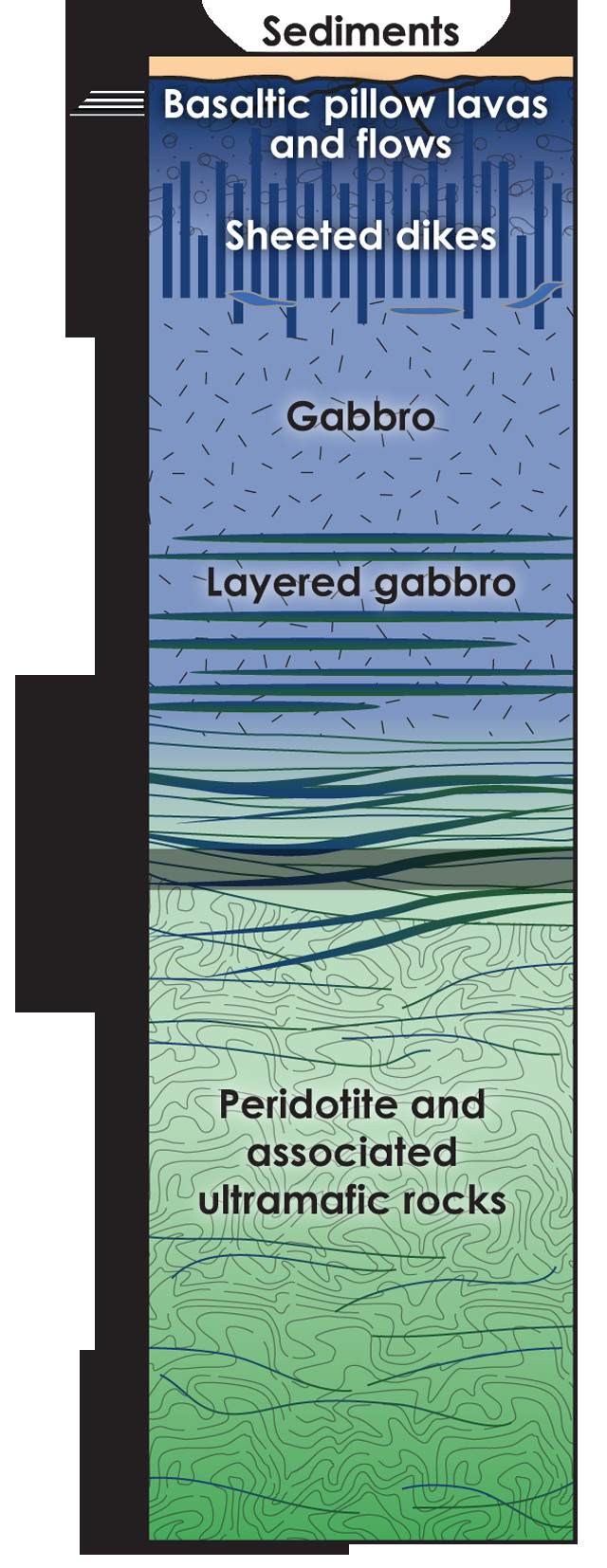

Simplified Ophiolite Sequence: Troödos ophiolite sequence consists of peridotite and associated ultramafic rocks, which are dense, coarse-grained igneous rocks predominantly composed of the greenish mineral olivine. These rocks comprise Earth's mantle. Above lies a section of layered gabbro (the intrusive equivalent to basalt). This is overlain by unlayered gabbro. Both types form from the underground injection and slow cooling of iron- and magnesium-rich magma into surrounding rocks. Above the gabbro lies a complex of sheeted dikes, which is particularly well exposed on Cyprus. These parallel, vertical dikes transported basaltic lavas from the magma chambers beneath the mid-ocean ridges to the ocean floor, where their eruption into seawater formed bulbous pillow lavas and other submarine volcanics, which are also on graphic display in the Troödos. This sequence of oceanic crust is overlain by marine sediments. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

In 1927, geologist Gustav Steinmann used the term “ophiolite” to describe a rock association he saw in the Austrian Alps that consisted of dense, dark-green rocks (called serpentinite due to their snakeskin-like resemblance), volcanic pillow basalts and deep-sea chert — an association that became known as Steinmann’s Trinity. Nobody thought much more about ophiolites until 1963, when Fred Vine and Drummond Matthews published their landmark paper positing that oceanic crust is formed at mid-ocean ridges via the process of seafloor spreading.

At about the same time, Ian Gass discovered, during his mapping of an ophiolite in Cyprus’ Troödos Mountains, a “sheeted dike” complex — a series of countless igneous intrusions, injected one inside another. Eldridge Moores and Vine soon realized that seafloor spreading was the only plausible mechanism by which to form the sheeted dike complex Gass had described. An ophiolite is thus a geologic rarity: a sliver of oceanic crust and underlying mantle that has been uplifted and emplaced on land. When this insight was combined with evidence for the destruction of oceanic crust in deep-sea trenches, scientists at last had the framework necessary to piece together the theory of plate tectonics.

Ophiolites are important tools for reconstructing ancient plate motion because they typically lie along the sutures that mark the locations of past plate collisions. Because ophiolites are associated with collision zones, they are typically sliced and diced by faults. Dismembered ophiolites occur all over the world but are rarely found intact. The Troödos ophiolite is one of the best, and careful mapping has allowed geologists to compare its rocks with the sequence that exists in modern oceanic crust, as revealed by ocean drilling. The results show that the Troödos ophiolite possesses the same succession of mafic and ultramafic (dark, iron- and magnesium-rich) igneous rocks that characterize modern oceanic crust, giving geologists confidence that ophiolites do indeed constitute pieces of ancient oceanic crust that somehow managed to end up on dry land.

Rocks of the Troödos ophiolite have been gently folded into a broad dome, the highest portion of which is 1,952-meter-high Mount Olympus, Cyprus’ highest peak. The deepest portion of the ophiolite sequence, a fragment of the mantle that underlies the oceanic crust, is exposed near the summit of Mount Olympus, in the center of the dome. The shallower, crustal portions of the sequence form concentric rings surrounding the Mount Olympus bull’s-eye.

Adjacent to the ophiolite lie a series of sedimentary rocks that accumulated on top of the newly minted oceanic crust. Among them are metal-rich sediments that spewed long ago from “black smokers,” geyser-like thermal hot springs that populate mid-ocean ridges, and were first discovered in 1977. Modern smokers host exotic, chemosynthetic animal communities that often include tubeworms, extremophilic archaea and other rare life-forms.

In the Akaki River Gorge, spectacular exposures of submarine pillow lavas (inset) are intruded by sheeted dikes. Credit: both: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Hikers can see the island's famous sheeted dikes along the 3.5-kilometer- long Teichia Tis Madaris Geo-Trail. Credit: both: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

The vast Troödos Geopark was recently established to promote public understanding of the Troödos ophiolite, and to protect it. The geopark covers nearly 137,000 hectares, or 15 percent of the island. Quite by accident, we were the very first visitors to the geopark’s brand-new visitor center, which is located in a restored elementary school near an old asbestos mine by Mount Olympus.

The Artemis Geo-Trail is an easy, 7-kilometer-long path that circumnavigates the summit of Mount Olympus, passing juniper and ancient black pine trees en route. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Exposures of different ultramafic mantle rocks, including peridotite, harzburgite, pyroxenite, serpentinite (seen here) and dunite, are labeled along the trail. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

The Paphos Archaeological Park hosts impressive Roman mosaics, such as a scene from the House of Aion (left) and a depiction of Theseus fighting the Minotaur in the House of Theseus (below). Credit: both: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

The visitor center displays detail the origin and uplift of the ophiolite. The story begins about 92 million years ago during the breakup of the supercontinent Pangea. The Tethys Sea had formed when two large landmasses, Laurasia to the north and Gondwana to the south, rifted apart. Gondwana further fragmented into several pieces, including modern Africa. As Africa moved northward, a subduction zone formed just north of the continent, within the oceanic crust of the Tethys Sea. The dense, old oceanic lithosphere that was attached to Africa sank rapidly into the mantle, creating a small oceanic spreading center located just above the subduction zone. The new oceanic crust of the Troödos ophiolite formed in that spreading center, making it what geologists call a supra-subduction zone ophiolite. Soon thereafter, African continental crust attached to the downgoing oceanic plate was shoved down into the trench. The buoyancy of the continental crust, however, blocked up the subduction zone and caused the doming of the ophiolite.

Following these tectonic fireworks, a period of relative calm prevailed in the area for tens of millions of years. Then, about 10 million years ago, another collision with a small, isolated piece of continental crust to the north of the island lifted the Cypriot rocks above the waves, raising the ophiolite dome as today’s Troödos Mountains.

The visitor center also features museum exhibits on the area’s mining history, including its famous copper deposits. These formed on the seafloor as a result of black smoker hydrothermal processes. Cyprus was an important center of Bronze Age copper production, beginning at least 5,000 years ago. The museum houses a collection of artifacts that illustrates that history, including a model of an ancient furnace used for copper production and Minoan copper ingots.

A roadside chapel along Cyprus' stunning south coast. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

While at the geopark visitor center, be sure to pick up a brochure to guide you along the Artemis Geo-Trail, the best place on Cyprus to walk through rocks that were once buried in the mantle. This easy, 7-kilometer-long trail circumnavigates the summit of Mount Olympus. Along the route you’ll see labeled exposures of different ultramafic mantle rocks, including peridotite, harzburgite, pyroxenite and dunite. The latter contains chromite, another important ore mineral. The geology unfolds as you hike through a beautiful forest consisting of giant black pine trees, gnarled with age, and foetid junipers. Interspersed with this forest are grasslands populated by a host of endemic grassland plants that grow exclusively on serpentine rocks.

Another excellent hiking choice is the Teichia Tis Madaris Geo-Trail. This undulating, 3.5-kilometer-long loop weaves through the island’s famous sheeted dike complex, which forms spectacular fins of black rock. These are just a few of the tens of thousands of dikes — ranging from centimeters to more than 10 meters in width — that comprise the complex. Each dike represents a conduit through which basaltic magma was injected onto the ocean floor at the mid-ocean ridge 92 million years ago. Because molten magma is hotter than the rock into which it’s injected, the edge of each dike cooled more quickly than the interior, creating a zone of finer-grained crystals along the dike’s perimeter. It was by the careful mapping of these “chilled margins” that geologists assembled overwhelming field evidence that the dikes formed during crustal extension at seafloor spreading centers.

A trip to the Troödos ophiolite would not be complete without a look at the spectacular exposure of submarine pillow lavas intruded by sheeted dikes along the banks of the Akaki River. The exposure lies just a few tens of kilometers south of the capital, Nicosia, and is newly marked with interpretive signs, courtesy of the geopark. Here, just a few steps from the road, is an amazing outcrop consisting of black hyaloclastites — rocks rich in basaltic glass formed by the immediate quenching of lava when it hit cold seawater — overlain by pillow lavas, whose bulbous shape forms from the extrusion of lava under water. Both are sliced by more dramatic vertical dikes.

Aphrodite's Beach is one of the most famous in Cyprus. The goddess is said to have been born as sea foam rising at Aphrodite's Rock, a towering chunk of fault-scored limestone rising dramatically from the sea. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

The Neolithic hillside village of Choirokoitia was built in about 6800 B.C. and is a World Heritage site. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

ne of the Tombs of the Kings, a series of underground tombs and rockhewn cavities where wealthy residents (not royalty) of ancient Paphos were buried during the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

In addition to its spectacular geoheritage, the Troödos Mountains are also world-famous for their Byzantine cultural heritage. Scattered across the range, quaint cobblestoned villages host a series of tiny Byzantine churches and monasteries, 10 of which comprise a UNESCO World Heritage site. Adorned with colorful frescoes painted as early as the 11th century, the Troödos painted churches were built by Orthodox Greeks who retreated to the mountainous slopes to escape religious persecution by the Lusignans. Especially stunning are the vivid 12th- through 17th-century frescoes in the Panayia Phorviotissa church, located in the village of Asinou, and the Panayia tou Arakou, in the village of Lagoudera, which hosts some of the best-known examples of the late-12th-century Comnenian artistic style.

Because the Troödos comprise a relatively compact area, it’s easy to combine a visit to several of the Byzantine churches with stops at local wineries. Archaeological excavations have revealed that Cyprus has been a hub of winemaking for more than 6,000 years. Today the industry is centered on the pretty village of Omodos, located on the Troödos Mountains’ fertile southwestern slopes. In this region, indigenous grapes, including the white xynisteri and the red maratheftiko varietals, are cultivated, crushed and fermented to create some delicious and relatively inexpensive wines. These wines pair perfectly with the wide assortment of mezes — small plates ranging from olives and tahini to sheftalia (spicy sausage) and calamari — often served for dinner, along with traditional, herb-infused Cypriot chocolates.

Beyond the mountains are many additional sites worth visiting, including the Paphos Archaeological Park. The site features a series of stunning mosaics that decorated the floors of wealthy Roman homes in the ancient city of Paphos, which was founded in the 4th century B.C. and ceded to the Romans in the middle of the 1st century B.C. Also of note are the nearby Tombs of the Kings, a series of underground tombs and rock-hewn cavities where wealthy residents (not royalty, mind you, despite the name) of ancient Paphos were buried during the Hellenistic and Roman periods. The island’s earliest permanent settlement, the Neolithic hillside village of Choirokoitia, was built in about 6800 B.C. and is another UNESCO World Heritage site.

As marvelous as Cyprus’ renowned historic sites and geology are, most visitors come here for its beautiful beaches. A particularly good choice for any geo-traveler is Aphrodite’s Beach. The goddess Aphrodite is said to have been born as sea foam rising at Aphrodite’s Rock, a towering chunk of fault-scored limestone rising dramatically from the sea. The goddess’ rock is part of a hodgepodge of different rock types belonging to the Mamonia Complex mélange. The mélange was emplaced on the opposite side of an ancient transform fault from the intact seafloor of the Troödos ophiolite.

In just a few days, we were captivated by Cyprus’ beauty, geology, historic relics and delicious food. Where else can you see stunning Roman mosaics in the morning and study intact oceanic crust in the afternoon? For these geo-travelers, that is a combination that is hard to beat, especially considering the compact island’s varied attractions can be easily visited as a brief part of a longer Mediterranean vacation.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.