by Mary Caperton Morton Tuesday, June 12, 2018

Today, Crater Lake in southwestern Oregon is known for being one of the deepest, clearest lakes in the world. In 5,700 B.C., however, the scenery stunned witnesses for a very different reason: The eruption and collapse of Mount Mazama that created Crater Lake is thought to be one of the greatest geologic catastrophes ever witnessed by humans. A trip to Crater Lake National Park will not only redefine your concept of nature’s bluest blue, but it’s also an opportunity to bear witness to the peaceful aftermath of one of Earth’s great cataclysms.

After a 400,000-year history of continuous but small eruptions that created a layered shield volcano, Mount Mazama reached a height of 3,700 meters about 8,000 years ago, but the apogee was not to last. About 7,700 years ago, the volcano literally blew its top. In a matter of days, Mount Mazama ejected some 50 cubic kilometers of pyroclastic ash and pumice, more than 50 times the amount spewed by the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens. Pyroclastic flows devastated the surrounding area, smothering the rivers that drained Mount Mazama and blanketing the land to the northeast with a layer of pumice and ash that extended as far as central Canada.

The huge volume of magma removed during the eruption left a massive void in the magma chamber beneath the mountain. Soon after the initial blast, Mount Mazama collapsed, leaving an enormous crater more than 1,200 meters deep and measuring 8 kilometers north to south and 10 kilometers east to west. Over the next 250 years, this crater filled with rain and snowmelt to create Crater Lake.

An artist's depiction of the eruption of Mount Mazama 7,700 years ago. The eruption left behind an enormous crater that filled with rain and snowmelt to create Crater Lake. Credit: Paul Rockwood Painting, courtesy of National Park Service, original in Crater Lake National Park Museum and Archives Collections

Credit: AGI/NASA

Crater Lake was preserved as a national park in 1902, but the clear blue waters have long been revered by the Klamath Native American tribe, whose Makalak ancestors lived near Mount Mazama and are thought to have witnessed the lake’s creation. Artifacts such as obsidian points and moccasins found beneath the ash layers from Mount Mazama’s eruption corroborate Klamath claims that their ancestors lived in the region at the time and likely witnessed the eruption firsthand.

Klamath legends passed down through generations in the native Modoc language neatly parallel what is known of the geologic history of Crater Lake. According to these legends, the entrance to the underworld was through a hole in the top of Mount Mazama, whose Klamath name translates as “the high mountain that used to be.” Disagreements between two gods — Llao of the Underworld and Skell of the World Above — led to an epic battle that culminated in the destruction of Llao’s underworld home and the creation of a peaceful lake in its place.

Any time of year is a great time to visit the remains of this epic battle, but recreational opportunities at Crater Lake vary widely with the seasons. For much of the year, snow rules Crater Lake. With an average snowfall of more than 13 meters a season, many park roads, including the stunning Rim Drive, are closed to cars from November until mid-June. The main entrance from the west, however, is kept open all year. If you do visit in winter, beware that snow chains or snow tires are recommended and in some places required. And bring your cross-country skis or snowshoes or rent a snowmobile — you’ll be treated to some of the most spectacular winter scenery in the Cascades. New to winter recreation? Don’t worry: The park service provides snowshoes for ranger-led hikes.

For many months out of the year, Crater Lake is home to a snowy landscape. Credit: courtesy of the National Park Service

Summer visitors should start by circumnavigating Crater Lake on Rim Drive by car or bike or on foot. The 53-kilometer-long loop skirts the edge of the crater, providing nonstop views of the blue waters below and the Cascade peaks beyond. Two visitor centers are staffed with knowledgeable rangers and feature displays on the geology, history and ecology of Crater Lake. Several shorter hikes along Rim Drive explore the crater rim, or if you’re looking for a longer hike, get a backcountry permit and hike the park’s 53-kilometer-long section of the Pacific Crest Trail, a 4,260-kilometer-long trail that runs from Mexico to Canada.

Once you’ve fully explored your options on the caldera rim, it’s time to touch the blue water below. Klamath men used to test their physical mettle by sprinting down the precipitous crater walls, but today the only access to the lakeshore is down the Cleetwood Cove Trail. The 3.5-kilometer-long round trip is a perilous 700-meter-loss-in-elevation slide down and a quad-busting haul back up, but seeing that blue water up close is worth the exertion. Remember to plan ahead and make reservations for a boat tour of the lake. Tours leave from Cleetwood Cove (you must be able to hike in and out of the crater to go) and are only available on clear days from mid-July through September.

A boat tour is the only way to get out on the water and see how clear it really is. With a maximum water depth of 594 meters — making Crater Lake the deepest lake in the U.S. and the ninth deepest in the world — you won’t be able to see the bottom; however, the water is so clear that you can see down as deep as 43 meters below the lake’s surface. This level of visibility places the lake among the clearest bodies of water in the world.

Crater Lake is currently home to two species of fish: kokanee salmon and rainbow trout (pictured here). Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Christian Nafzger

To this day, no streams flow in or out of Crater Lake, and the lack of organic materials, sediments and chemical pollutants flowing into the lake explains the lake’s exceptional clarity. The absence of streams also explains why, in more than 100 years of monitoring, the lake has only varied by five meters from its 1,883-meter elevation above sea level, with any change due solely to rain or snow, evaporation and seepage.

Because no streams flow in or out of the lake, no fish lived within the crater until 1888, when six species of trout and salmon were first introduced. The last fish stocking occurred in 1941, and since then, naturally reproducing populations of two species — kokanee salmon and rainbow trout — have thrived. Fishing is permitted at Crater Lake, though the sheer walls of the crater limit access to the lake water.

The best fishing opportunities are on Wizard Island, a volcanic cinder cone emerging from the west end of the lake. Wizard Island is one of several cinder cones that erupted from the caldera floor several hundred years after the destruction of Mount Mazama. Rising 2,113 meters above sea level, and 230 meters above the surface of the lake, Wizard Island is the only Crater Lake cinder cone that breaks the surface of the deep water.

An aerial view of Crater Lake. Credit: U.S. Geological Survey/Mike Doukas

The only access to Wizard Island is by boat, and visitors should be prepared to stay most of the day on the 128-hectare island because park service boats are often full to capacity. To pass the time, hike to the Witches Cauldron, a caldera at the summit of Wizard Island, or circumnavigate the base of the island on a flatter trail. Fishing, swimming and scuba diving are also permitted here, but be warned the water is frigidly cold.

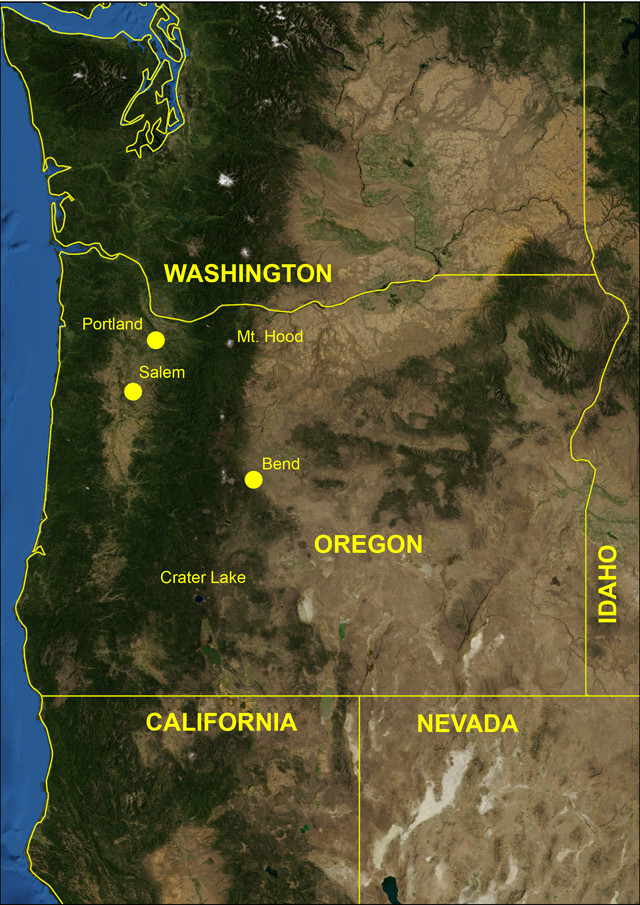

Many trips to Crater Lake National Park begin with a trip to Portland, with Mount Hood in the distance.Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/David Birkbeck

If you do take a dip, keep in mind that Crater Lake’s blue waters are held sacred by the Klamath tribe, who believe that the underworld spirits still lurk in the depths. Once again, the Klamath legends may come close to the geologic truth: The lake will not be a peaceful place forever. Hydrothermal activity still roils in the depths of Crater Lake, hinting at ongoing volcanism below. Someday, the Klamath’s god of the underworld may rise again.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.