by Anthony King Thursday, June 7, 2018

The Burren in western Ireland is one of the largest karst landscapes in Europe. Credit: ©Shutterstock.com/Pyma

The Burren — one of the largest karst landscapes in Europe — is a land of contradictions. In 1651, an English army officer noted that this region on Ireland’s west coast “is a country where there is not water enough to drown a man, wood enough to hang one, nor earth enough to bury him. This last is so scarce that the inhabitants steal it from one another and yet their cattle are very fat. The grass grows in tufts of earth of two or three foot square, which lies between the limestone rocks and is very sweet and nourishing.”

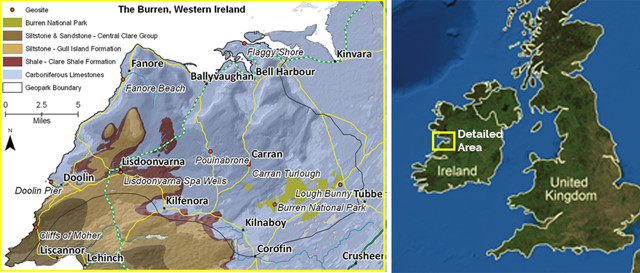

A geologic map of the Burren. Credit: AGI/NASA; data from the Geological Survey of Ireland/map by Ronan Hennessy

The Burren’s seemingly barren yet lush landscape arises from a karst terrain, filled with terraces of exposed limestone and rock that have been transformed over time by weathering and periods of glaciation. The area covers 360 square kilometers of Ireland, and is famed for its geology, botany and archaeology.

The Cliffs of Moher formed from delta sediments about 318 million years ago. Credit: ©Shutterstock.com/Patryk Kosmider

With few trees to offer shelter, a walk through the Burren can leave you chafed by rain driven onshore by Atlantic winds. You might glimpse an Irish hare, fox, stoat or an elusive pine martin across the landscape, or stumble across the rare and spectacular plants that sprout up between fissures in the limestone — nowhere else on the British Isles will you find such an odd mix of rare Mediterranean, Arctic and Alpine flowers.

These botanical species survive in a climate that is moist and mild. But the limestone originated in an even balmier world, more akin to the Bahamas of today. It formed in a warm, shallow Carboniferous sea about 330 million years ago when Ireland was 10 degrees south of the equator and largely covered by a sea that once extended across most of the British Isles and parts of northeast Europe. Fossils of corals, gastropods and crinoids (sea lilies) entombed in the limestone record the area’s marine origins.

About 326 million years ago, the basin of the tropical sea deepened rapidly and environmental conditions for limestone deposition ceased. For several million years, the only sediments that were deposited on the limestone in this deep sea were fine clay particles and the teeth and bones of fish that settled out of the water. This gave rise to a rich phosphate layer up to 2 meters thick that was mined to make fertilizer in the coastal village of Doolin, on the Burren’s southern end, during World War II.

The quiet depths of the sea were disturbed about 318 million years ago, when an influx of silt and fine sand built a slope at the mouth of a massive, complex delta system comparable to today’s Mississippi Delta. The sediments came from a landmass to the west and accumulated so quickly that they slumped down the slope before they lithified. Spectacular slump folds in the rocks can be seen at Fisherstreet Bay near Doolin, along with superb sand volcanoes, which formed from dewatering of the slump beds.

The rate of deposition from the delta was so fast that hundreds of meters of sediment accrued in less than 2 million years. You can see these deltaic sediments at the Cliffs of Moher, south of Doolin, with repeating cycles of sandstone, siltstone and mudstone. In places, you can see 30 meters of contorted sandstone and shale, which represent the collapse of the Upper Carboniferous basin sediment on the unstable delta slope.

The Burren is home to numerous karst limestone blocks (clints) that are dissected by fissures (grikes). Credit: ©Shutterstock.com/Javier Soto Vazquez

The limestone beds dip 2 to 4 degrees south in the north and west, the ripple effects of a mountain-building episode in southern Europe about 300 million years ago; this limited deformation probably reflects the stabilizing effect of the Galway granite; the granite pluton, which had formed 100 million years earlier and underlies the area, may have acted like a crustal root that withstood the stresses of the mountain building. Subsequent uplift of the Burren in the Mesozoic era opened cracks in the limestone, which were later exploited by hot mineral-rich fluids that left behind veins of calcite, fluorite, galena and pyrite. Many of these were mined on a small scale in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Geologists think the entire Burren rock sequence was uplifted in several phases over a period of about 250 million years, and the region has probably been above sea level for the last 50 million to 60 million years. The sandstone and shale that formed over the limestone blanketed the Burren until the start of the most recent Pleistocene glaciation; glaciers then removed much of the heavily weathered shale.

Patches of shale remain, however, forming uplands such as Slieve Elva, where rain runs off the shale and then disappears into the limestone through a series of sinkholes. Hiking over the shale, you may find spiral-shaped ammonoid fossils, extinct relatives of the squid.

Many people are drawn to the Burren for what’s beneath the ground: Rainwater has cut through the limestone to create a labyrinth of caves. The most extensive system is the Pollnagollum-Pollelva complex, which has been mapped for 13 kilometers, with more waiting to be discovered. The caves meander in dark twisting passages and canyons, with streams exploiting joints in the limestone and producing sharp bends and vertical drops. The two main entrance points are the gaping potholes of Pollelva, which drops 30 meters straight down, and Pollnagollum, 40 meters across and 25 meters deep. The water from this system follows dry valleys and eventually rises at the shale-limestone boundary at St. Brendan’s Well, a karst spring near the town of Lisdoonvarna.

There are nine major underground drainage systems in the Burren, and the Clare Caving Club often organizes trips to some of them on the first Sunday of each month. But if you want to explore these areas, expect to get wet. Visitors must swim to experience the marvels of the Doolin and Coolagh river cave systems, where temperatures are a cool 9 degrees Celsius (roughly 50 degrees Fahrenheit). Some of the most famous caves are south of Ballyvaughan on the north coast of the Burren, where the Cave of the Wild Horses discharges, flooding the surrounding countryside during winter. The cave’s name comes from a local legend that a herd of wild horses would spring from the cave annually to ravage the countryside.

In addition to the subterranean rivers, there are a few rivers aboveground, but they too eventually go underground, disappearing into sinkholes only to re-emerge as springs, both on and offshore.

If you’d rather stay on the surface, consider walking the 123-kilometer Burren Way trail. The trail begins at Lehinch on the western side of the Burren. The trail’s mix of green roads, pathways, old roadways and minor roads will take you past the Carran Depression in the heart of the Burren — Ireland’s best example of a doline, or a closed depression. In winter, the turlough here is the largest in the Burren and supports a few hundred ducks. Turloughs are seasonal lakes that disappear and reappear depending on the water table and are often connected to the sea by underground passages and therefore are affected by the tide. When a turlough vanishes, a lush, verdant lawn often takes its place.

If you travel through the Burren in winter, you may be surprised to see cattle grazing the uplands.

Livestock in Ireland are usually brought down from the hills during winter, but in the Burren, the limestone soaks up heat in summer and releases it during winter, keeping the ground warmer year-round. Drinking water for the cattle is also still available in the depressions in the rocks during this time of year. This millennia-old practice also explains why the Burren is home to a beautiful carpet of flowers in spring: The cattle wander through rock-strewn pastures and graze down the coarse grass during winter, allowing for a spring bloom of wildflowers such as the blue spring gentians and cream mountain avens. Orchids are also everywhere; the Burren hosts 23 of Ireland’s 25 species of the flower. Visitors can learn more about the area’s cattle and farming practices through Clare Farm Heritage Tours, which offers daily farm heritage tours during summer.

The more discriminating geo-tourist may notice the Burren is not just a karst terrain, but actually a glaciokarst area, having been modified and influenced by glaciation. Fields of bare karst limestone blocks, called clints, are dissected by fissures, or grikes. There is clear evidence for two episodes of glaciation moving through the Burren. An earlier glaciation about 250,000 years ago moved ice across Galway Bay from Connemara and covered the entire area, leaving erratic boulders of Galway granite behind when it retreated. The final advance 60,000 years ago was less extensive, only covering the eastern Burren, where it replaced the granite boulders with its own limestone erratics. Today, remaining granite erratics, found mostly on the hill summits of the northern Burren, demonstrate that the ice sheet was at least a couple of hundred meters thick.

The Pleistocene Ice Age ended in Ireland about 13,000 years ago, at which time the Burren may have had a thin covering of soil. Today, the rich glacial soil remains in the valleys, but it mysteriously disappeared from the bare limestone terraces that comprise one-fifth of the Burren. The debate about what happened to the soil is somewhat contentious. Some ecologists say prehistoric farmers chopped down native hazel woods and denuded the landscape of soil, leaving the rock bare. Other ecologists suggest our ancestors are not to blame; they say the soil was so thin that it was inevitable that it would weather away in a karst landscape like the Burren.

If you need a break from the rocks and caves, the Burren offers a range of relaxing and entertaining activities. Doolin is famous for its traditional Irish music, and it’s an excellent place to take in the “craic” — as they say in Ireland, or “good cheer” — or to listen to local banter in a selection of lively pubs. Pints of dark beer may line up in front of the musicians for refreshment, as stout is a favored brew in this part of the world.

The town of Lisdoonvarna — in the southern Burren, which hosts a singles matchmaking festival each September reputed to be one of Europe’s largest — is a good place to visit after a day of trekking: It’s the site of luxurious spas. The spas’ waters pick up leached sulfur and iron from the region’s shale — another example of how just about everything in the Burren is rooted in the region’s rich geology.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.