by Terri Cook Thursday, May 24, 2018

The Bay of Kotor formed when rising sea levels drowned an ancient river valley — a geographic feature called a ria. Credit: Background: ©Shutterstock.com/Gerardo Borbolla; left: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott

With its stunning backdrop of steep, imposing cliffs that plummet to a narrow inlet of the sparkling Adriatic Sea, Montenegro’s Bay of Kotor is often called Europe’s southernmost fjord. But this is a mistake. Unlike the finger-like inlets adorning the coasts of more famous European destinations like Norway and Iceland, the Bay of Kotor was not carved by glaciers. This impressive bay was instead created when rising sea levels drowned an ancient river valley — a feature geomorphologists call a ria.

A ria typically has a branching outline inherited from the former river valley’s dendritic drainage pattern and is characterized by a large estuary at the mouth of a disproportionately small river. Because rias remain open to the sea, they usually form excellent natural harbors. San Francisco Bay, Chesapeake Bay and Australia’s Sydney Harbor are all familiar examples.

Most visitors to the Bay of Kotor arrive via cruise ship or an all-day excursion from Dubrovnik, Croatia, and only spend a few hours here. But the walled old town of Kotor and the bay's many other attractions merit a longer stay. Visitors who want to linger can fly into Tivat airport, located 8 kilometers from Kotor, or Dubrovnik (about a two-hour drive), or can take a ferry from Ancona or Bari, Italy, to Montenegro's Port of Bar, situated 60 kilometers southeast of Kotor. Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI

The Bay of Kotor ria has an unusual bay-within-a-bay configuration: a coastal inlet that opens up into an outer bay, which then narrows to the 300-meter-wide Verige Strait before opening again into a 7-kilometer-wide inner bay. Thanks to this strategic and sheltered location, the Bay of Kotor has been the setting for a long and fascinating human history.

Viewing ancient Roman mosaics in Risan, sipping local wine amid Perast’s maze of cobblestone lanes, and hiking the medieval fortifications around the walled old town of Kotor are just a few of the highlights of exploring the World Heritage Site that is Europe’s southernmost “fjord.”

The Dinarides

Montenegro is a mountainous and sparsely populated country (about the size of Connecticut but hosting a population of just 632,000, almost six times smaller than Connecticut’s) in the Dinarides, a rugged chain of mountains that stretches along the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea. The story of the mountains’ formation begins during the breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea about 200 million years ago, when a rift formed between the ancient landmasses of Laurasia to the north and Gondwana to the south. This rift gradually grew into the Tethys Sea, the floor of which was covered with thick piles of shallow marine carbonates during the Mesozoic era.

As Pangaea continued to split apart at the seams, Earth’s plates slowly reorganized themselves. Northward movement of Africa created a series of subduction zones along the Tethys Sea’s northern edge that culminated during the Cenozoic in a series of continental collisions that raised mountain ranges, including the Alps, the Pyrenees, the Carpathians and the Dinarides.

The Dinarides are a series of roughly parallel ranges that run southeast from Slovenia’s Julian Alps to Albania. The thick sequence of Tethyan carbonates were thrust around an old, rigid block of crust, bending the ranges into the large arc we see today. Much more recently, during the Pleistocene, the highest Dinarides were modestly glaciated, putting the finishing touches on the Bay of Kotor’s spectacular backdrop.

A Dynamic History

In recognition of the region’s cultural and historical significance as well as its stunning natural beauty, the United Nations inscribed the bay and the old town of Kotor, one of the Adriatic’s best-preserved medieval towns, on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1979. The area’s long and fascinating history is best explored by driving along the bay’s twisting shoreline, drinking in the stunning views and stopping at the many attractions en route.

Neolithic ceramics found in Vela Spila Cave, located near Risan on the inner bay’s northwestern corner, indicate the area was inhabited by roughly 5000 B.C. Nearby cave paintings at Lipci Rock, which depict a group of deer running in front of mounted hunters, as well as a boat, date to at least the Bronze Age. Other archaeological evidence, such as burial mounds, indicates that by 1000 B.C. Illyrian tribes inhabited the area. By 400 B.C., the Greeks had established several colonies around the bay, and when the Illyrian queen Teuta attacked them in 229 B.C., the Greeks asked the Romans for protection.

The floors of a third-century Roman villa in Risan are still decorated with vibrant, geometrically patterned mosaics, such as this one depicting Hypnos, the Greco-Roman god of sleep, reclining in a chair. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Vladimir Popovic

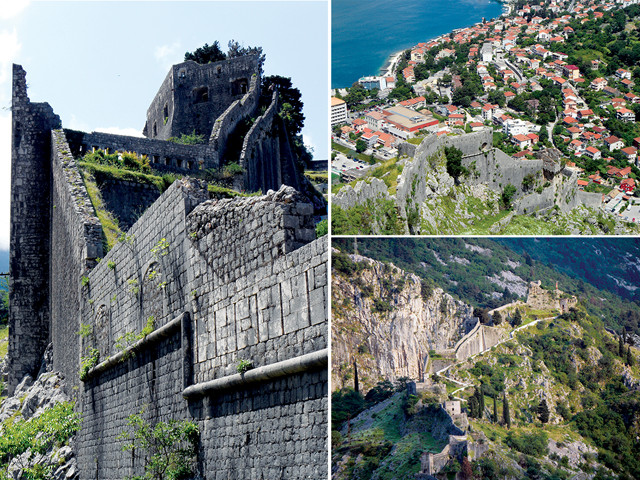

Exploring Kotor's thick fortifications, originally built in the ninth century, is one of the bay's highlights. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott

"Old Town" Kotor is reminiscent of old Italian towns — for good reason. Kotor's present appearance is primarily the result of four centuries of Venetian rule. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott

After defeating the Illyrians, the Romans ruled the bay for the next 500 years, until the fall of their Western Empire in the late fifth century. Both Risan and Kotor were Roman colonies, and a highlight of any modern trip to the bay is visiting the remains of Risan’s third-century Roman villa, whose floors are still decorated with vibrant, geometrically patterned mosaics. The most famous mosaic, located in the master bedroom, depicts Hypnos, the Greco-Roman god of sleep, leisurely reclining in a lounge chair.

The winged lion (above right), the symbol of Venice, appears near the western Sea Gate (above) upon entry to the old town of Kotor. A separate entrance, the Gurdić, or South Gate (right), adjoins a drawbridge over a spring that once served as an important source of water for Kotor. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott

During the Middle Ages, the bay remained an important harbor and trading hub, and the town of Kotor developed into a significant commercial and artistic center. Through the centuries, various entities — including Serbian emperors, the Venetians and the Ottomans — fought for control of the town. The French occupied Kotor for most of the 19th century, followed briefly by the Austrians until 1918, when Kotor became part of Yugoslavia. Most recently, in 2006, the Montenegrins voted for independence from Serbia, thus establishing one of Europe’s youngest nations.

The region’s complex history is reflected in its architecture. Perched across from the bay’s narrow straits, the town of Perast has an interesting museum emphasizing its seafaring history plus several dozen monuments, including palaces, churches, and defensive towers, which showcase its heady days as a prominent Venetian outpost. At the outer bay’s southwestern corner, hilly Herceg Novi hosts an eclectic mix of monuments — from the Bloody Tower, a large fort that served as a notorious Turkish prison, to an impressive Austrian clock tower — reflecting its succession of rulers.

Just offshore of Perast are two picturesque islands that you can easily visit: St. George, a natural isle that hosts a Benedictine monastery sheltered by tall cypress trees, and the larger, man-made Lady of the Rock Island. According to legend, in the 15th century two sailors found a picture of the Virgin Mary on a rock jutting out of the bay here. People from Perast began sinking rocks and old ships at the site to create this island, a tradition they continue each year on July 22. In 1630, a beautiful chapel was built on the artificial island. Still standing today, the chapel hosts paintings and other precious gifts donated to Our Lady.

The jewel of the bay is the wonderful old town of Kotor, whose impressive 4.5 kilometers of encircling fortifications are visible from across the bay. Kotor’s sturdy walls, which reach up to 20 meters high and range from 2 to 16 meters thick, were started in the ninth century and modified up until the 18th. For visitors who like to hike, the spectacular view after ascending the 1,200 meters to Castel St. John, built on the site of an old Illyrian fort at the top of the ramparts, is a rich reward. At night the walls are lit up, welcoming visitors to the old town’s labyrinth of cobblestone streets lined with fashionable shops, historic churches, shady cafes, and tempting gelato stands.

Kotor’s present appearance is primarily the result of four centuries of Venetian rule. This is evident when you enter the old town through the western Sea Gate, above which the winged lion — the symbol of Venice — is proudly displayed. Upon entering, your first glimpse is of the beautiful town clock tower, built in 1602, that dominates the imposing Square of Arms.

Classic Karst

While the succession of cultures that have inhabited the area may be challenging to remember, the rock identification is unusually easy: Virtually all the rock you see is carbonate — grayish-white limestone (composed of calcium carbonate) and dolomite, its more magnesium-rich cousin.

An interesting characteristic of limestone and dolomite is that they are very resistant in arid environments, but in wetter conditions, they dissolve easily from the slight natural acidity of rain and groundwater. In areas like the mountains above the Bay of Kotor, where carbonates are the dominant rocks and wetter conditions prevail, a type of dissolution topography, known as karst, has formed.

Karst topography forms when slightly acidic water begins to dissolve fractures or bedding planes in the carbonates. Continued dissolution gradually enlarges the fractures, allowing more water to pass through and accelerating the development of an underground drainage system that can include caves, sinkholes, disappearing streams, and springs that seem to appear out of nowhere. The former Yugoslavia is where karst topography was first described, and the word “karst” is thought to derive from an Illyrian root.

Classic karst topography includes caves, sinkholes, disappearing streams, and springs that seem to appear out of nowhere. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott

For stunning bird’s-eye views of the karst, Kotor’s fortifications and the bay, drive up the “ladder of Kotor,” a steep, paved road that zigzags through 25 hairpin bends up the mountain front from Kotor to Lovćen National Park. As you drive around, you’ll notice the relative lack of surface water, one of the most distinctive features of karst topography because any moisture that falls on the ground quickly enters the underground plumbing. One such drainage system reaches the surface at a cave just before Lovćen Pass. A spring surfaces inside the cave, causing water to pool up on its floor.

The development of extensive underground drainage networks in karst often poses unusual environmental challenges, including to water supplies and sewage and wastewater disposal. Securing enough freshwater in the region is an ongoing challenge; from 1915 to the late 1970s, all the sources of water in the Kotor region were developed, but there is still not enough to meet the needs of the town. The situation is exacerbated during the dry summer season, when local springs become brackish due to saltwater intrusion. Due to the area’s abundance of limestone, there are similar water supply problems all along the Montenegrin coast, and much of this young nation’s recent geological research has focused on improving the population’s tenuous water supply.

Left: St. Tryphon Cathedral, originally constructed in the 12th century and damaged by earthquakes, had to be rebuilt after its frontage was destroyed in an earthquake in 1667. Its northern bell tower was never finished. Right: The clock tower in Kotor was tilted during the same earthquake in 1667. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott

An Evolving Landscape

Another challenge is the geologic hazard posed by the earthquakes that continue to threaten the region. A series of large tremors in the 16th and 17th centuries damaged many of Kotor’s buildings, leaving a lasting impact on its architectural treasures. The town clock tower was tilted during an earthquake in 1667, and St. Tryphon Cathedral, originally constructed in the 12th century and already damaged by earlier earthquakes, had to be rebuilt after its frontage was destroyed in the same temblor. It was at this time that the cathedral’s distinctive baroque bell towers were added, although the northern one was never finished.

More recently, on April 15, 1979, a shallow, magnitude-7 earthquake devastated the region, killing about 150 people, injuring more than a thousand, and creating extensive damage along what was then the southwestern Yugoslavian coast. An estimated 600 of the bay’s historical monuments were seriously damaged, including Kotor’s walls, which have since been restored.

Just as the histories of the people living along the bay continue to unfold, the geologic processes that uplifted the mountains that comprise the bay’s spectacular backdrop continue to shape the area today. Whether you call the Bay of Kotor a “fjord” or a “ria,” its amazing views, dynamic geology and rich history are well worth the detour to see.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.