by Mary Caperton Morton Tuesday, July 1, 2014

Sunset on the Giant's Causeway. The Causeway Coast Way runs along the cliffs above. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

Like its neighbor to the south, Northern Ireland is renowned for its green vegetation, but the rocks that underlie this part of the Emerald Isle are also legendary. The Antrim Coast famously hosts one of the most striking examples of columnar basalt in the world, the Giant’s Causeway, which, according to legend, was built by a brawling giant. Other local lore tells of island cave hideouts, shipwreck massacres and Viking sieges.

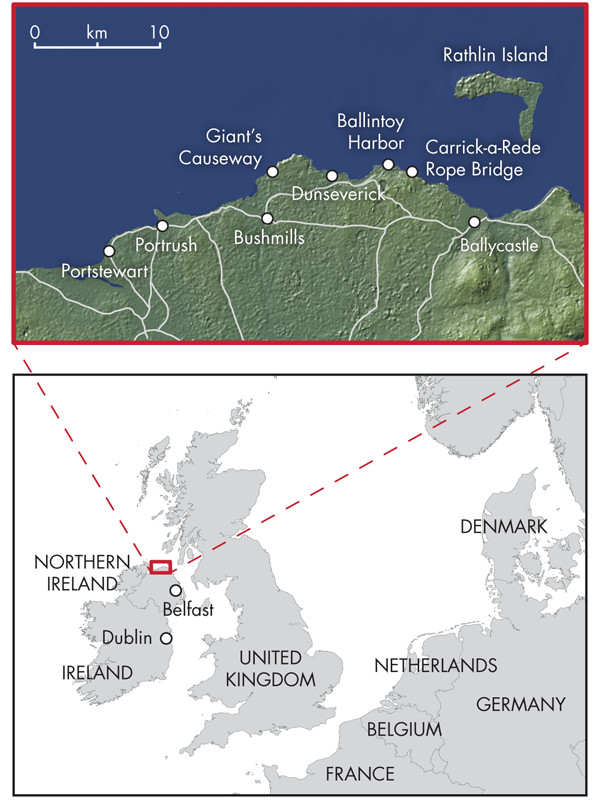

One of the best ways to experience some of the country’s mythic geology is to take a hike along all or part of the spectacular 53-kilometer Causeway Coast Way, which runs along the precipitous edge of Northern Ireland between Ballycastle and Portstewart. The hike can be completed in its entirety in two to three days in either direction or done in shorter sections. Hiking the whole trail is made easier by convenient public transportation and ample overnight accommodations along the way.

Credit: maps: Kathleen Cantner.

Before setting off from Ballycastle, you might first want to take a ferry detour out to Rathlin Island, the only inhabited island off Northern Ireland’s coast. This tiny, L-shaped chunk of rock, only 6 kilometers long and 4 kilometers wide, is home to about 100 people and tens of thousands of seabirds, including common guillemots, puffins and kittiwakes that flock to the island’s 70-meter-tall basalt cliffs.

In 1306, the future King of Scots, Robert the Bruce, hid out from the English on Rathlin Island in a sea cave below what is now the East Lighthouse. The cave proved a good hideout then and it still is today; to visit, you’ll need a sturdy boat and some serious navigational skills to avoid the same fate that befell dozens of shipwrecks littering Rathlin’s rocky shores.

West of Ballycastle swings the Causeway Coast’s most adventurous attraction: the Carrick-a-Rede rope bridge. Each spring, for more than 250 years, fishermen have erected a 20-meter-long woven bridge to connect the mainland to this small island off the coast. The name Carrick-a-Rede means “rock in the road,” a fitting moniker for this rocky obstacle that sits directly in the path of migrating salmon. The island is an eroded volcanic plug that remains from multiple violent eruptions 60 million years ago. Whereas much of the Causeway Coast is basalt, Carrick-a-Rede is made of harder dolerite, which contains evidence of explosive breccias and volcanic bombs.

These days, the migrating salmon are few, but the rope bridge remains up year round to net thousands of tourists willing to pay about $8 to cross the swinging expanse over the bright blue waters of the North Atlantic. Carrick-a-Rede overlooks Rathlin Island and on clear days, you can see all the way to the Mull of Kintyre, the southernmost tip of southwest Scotland. During the last glacial maximum, when sea levels were lower, the Mull of Kintyre is thought to have created a land bridge between Scotland and Ireland, facilitating early human migration between the islands.

Clockwise from top: One of many creeks running through layers of black basalt on its way to the sea; a unique polygonal tide pool at the Giant's Causeway; wave action has carved arches and sea stacks out of the limestone around White Park Bay. Credit: all: Mary Caperton Morton.

If you’re looking to hike a one- to two-day section of the Coast Trail, you can leave a car at Carrick-a-Rede and start hiking west to the Giant’s Causeway, a 20-kilometer trek. The beginning of this section passes between farms before winding down to picturesque Ballintoy Harbor and then across a 2-kilometer-long crescent of golden sand known as White Park Bay. Before setting out, check tide charts, as this section is only accessible at low tide. If the tide is high, you’ll have to follow the A2 road inland from Ballintoy to Dunseverick village.

White Park Bay is enclosed by high chalk cliffs reminiscent of the famed White Cliffs of Dover in southern England. The bay is littered with seaweed-covered boulders, and sea arches and stacks made of Cretaceous limestone. People have occupied White Park Bay for millennia: A prehistoric burial mound, several passage tombs and a number of neolithic stone and bone tools have been recovered from the beach and surrounding dunes. The White Park Bay Youth Hostel, overlooking the beach, is an inexpensive, idyllic place for an overnight stay.

Clockwise from top left: The remains of Dunseverick Castle, one of several fortresses along the Antrim Coast; the tiny hamlet of Portbradden; geologically themed signage ("Road liable to subsidence") on a dirt road out to Fair Head, one of the best rock climbing locales in the United Kingdom. Credit: all: Mary Caperton Morton.

Past White Park Bay, the Causeway Coast Way runs through the tiny hamlet of Portbradden, through green pastures grazed by cows and sheep, and crosses a bridge over a creek that cuts down through dark basalt rocks and spills over a waterfall into the sea. Soon you’ll come to a sharp peninsula of grass-topped basalt graced by the picturesque limestone-block ruins of Dunseverick Castle. This fortress dates back to at least the fifth century A.D., when Saint Patrick himself visited the site and blessed the castle’s well. In 870, Vikings ransacked the fort, which was rebuilt in about 1000 only to be soundly destroyed again by Oliver Cromwell’s army in 1641.

From here, the route climbs over 100-meter-high cliffs overlooking the North Atlantic. Below the cliffs, you might spot some kayakers heading to the Port Moon Bothy, an off-grid hut accessible only by water. The path climbs gradually to the highest point of the trail at Hamilton’s Seat on the tip of Benbane Head headland, where you can see White Park Bay to the east and the Giant’s Causeway to the west.

The cliffs along this section of coast are made mostly of columnar basalt pocketed by a series of steep-sided coves, one of which hides the wreck of the Girona, a ship of the Spanish Armada that sank in a storm in October 1588, drowning all but nine of the 1,300 people on board. In the 1960s, a dive team investigated the wreck and recovered a massive haul of Armada treasure, including copious gold coins and dozens of brass cannons, now on display in the Ulster Museum in Belfast.

Clockwise from top left: Looking down on the Giant's Causeway from the cliff-top Causeway Coast Way. The Little, Middle and Grand Causeways run left to right; the Causeway's stones are stable, but can be slippery when wet; early mornings are often the best time to visit the Causeway, which can get very crowded once the shuttle buses start running from the visitor center. Credit: all: Mary Caperton Morton.

Descending from Benbane Head, you’ll soon spot the towering basalt columns known as the Giant’s Chimney, the gateway to the Giant’s Causeway, Northern Ireland’s only natural site on the UNESCO World Heritage List. The view from the cliff-top trail overlooking the Causeway reveals the site’s surprisingly diminutive size: Three narrow promontories run down into the sea along a small section of coast. To better appreciate the Causeway’s unique rocks, descend the Shepherd’s Steps — 162 steep, narrow stone steps carved into the cliff centuries ago — and walk out onto the Causeway’s hexagonal stones.

About 60 million years ago, during the Paleogene, when the Atlantic Ocean was opening between North America and Europe, a spate of violent volcanism pushed molten basalt up through the soft chalk beds of Northern Ireland, erupting a massive lava field called the Thulean Plateau along what is now Northern Ireland’s Antrim Coast. As it cooled, this large mass of homogeneous basalt contracted along natural joints, creating regular vertical columns that were originally 100 meters tall. Over time, wave erosion shortened many of the columns and sculpted out three promontories, made up of more than 40,000 hexagonal basalt columns known as the Little, Middle and Grand Causeways. Much taller columns can still be seen lining the cliffs above the Causeway.

Erosion has closed part of this trail out to the Giant's Chimneys. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

Most of the Causeway’s columns are hexagonal, although there are also numerous five- and seven-sided stones and a few four- and eight-sided stones. The pillars are actually stacked segments fractured horizontally into “biscuits” that are convex on the bottom and concave on the top, producing the well-fitted ball-and-socket joints that make for the Causeway’s stable, but sometimes slippery, stepping-stones.

The Giant’s Causeway has been a tourist attraction since at least the 19th century, when a narrow gauge electric tramway ran from Portrush to the site. Today, a state-of-the-art visitor center is built right into the landscape — a section of the Causeway Coast Way actually runs over the building’s grassy roof. Visitors can elect to bypass the building and walk the 1-kilometer-long paved path to the Causeway for free or pay about US $15 per adult or $7.50 per child to browse through the center’s museum and gift shop and catch a ride on a shuttle bus down to the Causeway itself.

Limestone rocks are scattered around White Park Bay. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

The Giant’s Causeway is the highlight of the Causeway Coast, but the trail keeps running west for another 25 kilometers to the posh seaside resort of Portstewart. Thirsty hikers might want to detour inland to sip some whiskey in Bushmills, home of the world’s oldest distillery, in operation since 1608.

Or, if your legs are still working and your geo-curiosity is still buzzing, head to Whiterocks Beach in Portrush to see limestone cliffs riddled with caves and arches. Laid down during the Cretaceous, when this part of the world was under a warm, shallow sea, Northern Ireland’s white cliffs are rich in fossils such as echinoids and belemnites. Considered one of the finest beaches in the United Kingdom, Whiterocks is a fine place to rest trail-weary legs and watch the sun set over the North Atlantic.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.