by Terri Cook and Lon Abbott Monday, August 4, 2014

Australia, having experienced little recent tectonic activity, is the world’s lowest and flattest continent on average. But don’t take that to mean it’s geologically boring. It is this very quiescence that has ensured the preservation of a remarkable record of early-Earth events on the continent: from mineral grains only slightly younger than the planet itself, to a glacial event so severe that geologists call it “Snowball Earth,” to an unparalleled record of life’s early evolution. To see the ancient rocks that hold this record, you must leave the comparatively lush coastal strip — home to 90 percent of Australia’s population — and venture into the vast, arid interior wilderness known as the Outback.

Credit: both: Kathleen Cantner, AGI.

We first experienced the Outback in 1995 on a typical graduate student’s shoestring budget, touring the country in a car we rented from an outfit named “Rent a Bomb.” It lived up to its name, breaking down outside Coober Pedy, a lonely town famous for searing heat, underground homes called dugouts and the planet’s largest opal mining area. Perhaps inspired by the surroundings — or maybe by the knowledge that opals are cheaper than diamonds — Lon proposed there, and we shopped together for Terri’s opal engagement ring.

Our second Outback excursion in 2010 was through the state of Western Australia, which is larger than Texas, Japan and the British Isles combined. Western Australia is formed from three chunks of Archean lithosphere (older than 2.5 billion years) that amalgamated during a series of collisions ending about 1.6 billion years ago. We made a pilgrimage to Marble Bar, an old mining town that in the 1920s set the world record for consecutive days (160) exceeding 37.8 degrees Celsius (100 degrees Fahrenheit). Marble Bar is home to 3.5-billion-year-old cherts — a type of microcrystalline quartz — that contain stromatolites (layered sedimentary rocks or columns produced by the ancient activity of cyanobacteria) interpreted as the earliest evidence of life on Earth.

This past spring, we found ourselves in Australia again, living Down Under while Lon was on sabbatical. Our two children — evidently inspired by our earlier tales of adventure — wanted to journey to the “Red Center,” an expanse of red rocks and sand dunes that make up the very heart of the Outback. Not wanting to limit ourselves to paved roads (or to experience another “Rent a Bomb”-breakdown with the kids), we rented a four-wheel-drive vehicle, complete with rooftop tents — to keep us away from various slithering and hopping creatures — and hit the road for an unforgettable Aussie Outback Adventure.

The story of the Red Center begins in the middle of the Proterozoic, when massive collisions welded proto-Australia’s Archean craton to youthful incarnations of Antarctica, India and North America. By about 1.1 billion years ago, all of the planet’s landmasses were united in a vast supercontinent known as Rodinia. Then, some 850 million years ago, Rodinia began splitting apart. As the continental fragments went their separate ways, extension within central Australia created a deep trough called the Amadeus Basin, where thick sedimentary layers, including some of the world’s earliest-known major salt deposits, were laid down.

One of the Amadeus’ oldest layers is the Heavitree Quartzite, a sandstone later metamorphosed into the hard quartzite that today forms many of the Red Center’s spectacular cliffs. Red Center rocks also contain records of Earth’s first multicellular life, its first vertebrates, and several of its most severe glacial events.

After Earth emerged from this deep freeze, a big mountain-building episode known as the Petermann Orogeny took place in central Australia near the end of the Proterozoic about 600 million years ago. This episode was associated with the assembly of Gondwanaland, one of the major pieces of Earth’s next supercontinent, Pangaea.

Central Australia’s most recent mountain-building episode — the Alice Springs Orogeny — occurred between 400 million and 350 million years ago and also reshaped the continental interior. This event was the last tectonic episode needed to create today’s Outback scenery.

Our Outback adventure began north of Adelaide in Flinders Ranges National Park, widely considered to possess the world’s best record of Earth events during the Neoproterozoic, between 1 billion and 542 million years ago. The portion of this record spanning 650 million to 500 million years ago — a critical period in Earth’s climatic history and the evolution of life — is beautifully dis"layed along a rough, dirt road that requires a four-wheel-drive vehicle and winds through the park’s scenic Brachina Gorge.

Of special interest at Brachina is the 620-million-year-old Elatina Formation, which contains tillite, poorly sorted sediment dumped by a glacier. According to paleomagnetic studies, when the Flinders Ranges sediments were deposited, they lay just 8 degrees south of the equator (today it’s at 31.4 degrees south). For the massi"e glaciers necessary to produce such tillites to have existed in tropical latitudes, virtually the entire Earth must have been frozen, leading geologists to label this and other similar Late Proterozoic episodes as “Snowball Earth” events.

The Elatina rocks are overlain by the 610-million-year-old Nuccaleena dolomite, which indicates the presence of a warm ocean and records a rapid climatic shift from intense cold to sweltering heat. Only the heartiest of bacteria could have survived these shifting climatic extremes. In the world’s earliest example of the adage “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” strains of surviving bacteria eventually evolved to become Earth’s first multicellular organisms, the Ediacaran fauna.

These animals were soft-bodied, and many boasted tentacles and/or multichambered bodies somewhat similar to modern jellyfish, sea pens or segmented worms. In the absence of predators, many of them grew large, up to a meter across. In 1946, the first Ediacaran fauna were discovered in (and named for) the nearby Ediacara Hills, and Brachina Gorge contains the type section for the Ediacaran Period in which they flourished. The fossils are found in the 550-million-year-old Rawnsley Quartzite, which is so resistant to erosion that it forms the park’s most spectacular topography. To protect this invaluable resource, no fossils are displayed along the road, but there is an excellent Ediacaran exhibit at Adelaide’s South Australian Museum.

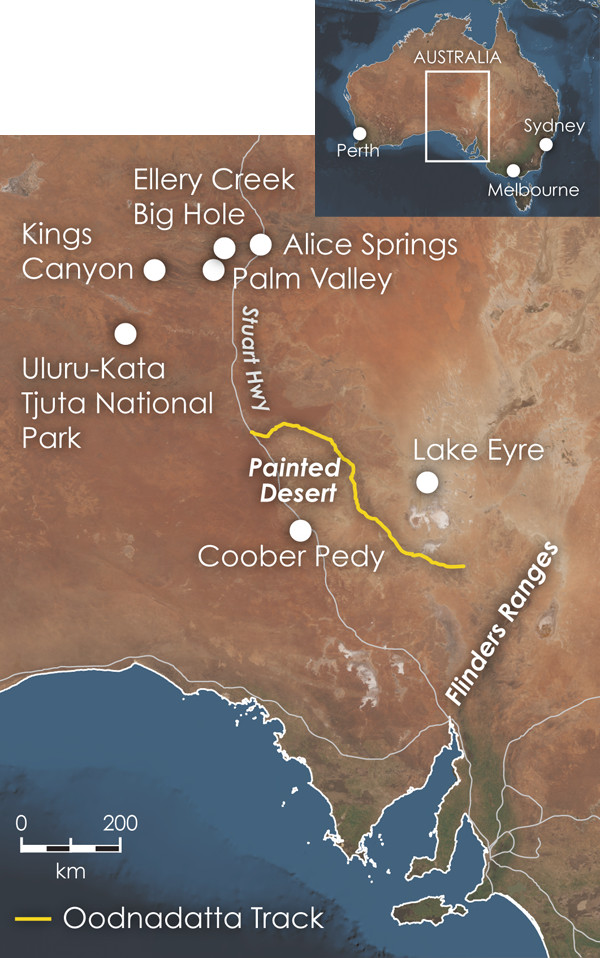

North of the Flinders Ranges, our beefy four-wheel-drive vehicle enabled us to tackle one of Australia’s most famous Outback adventures: driving the history-steeped, 620-kilometer-long Oodnadatta Track. It follows the trace of the Overland Telegraph Line and the subsequent Central Australian Railway (later called the Ghan). Construction of the telegraph line in the 1870s was a great engineering feat that finally linked Australia with the rest of the world.

Following a string of mostly cold springs that Aboriginal people have traveled among for millennia, the Overland route was initially mapped by the Scottish explorer John McDouall Stuart, the first documented European to visit the Red Center. The Ghan Railway was later laid in roughly the same location because its steam engines required a water refill every 30 kilometers. Much of the Oodnadatta Track’s charm emerges in exploring the springs and the ruins, while contemplating the lives of the people who eke out an existence in this harsh land.

Despite the flies and the heat, our kids enjoyed climbing Hamilton Hill, a mound of limestone rock precipitated from the water of an extinct spring, and strolling to the Bubbler, a gurgling spring that local Aborigines believe was a writhing snake killed by their ancestors and later cooked in the Blanche Cup, another nearby spring.

The springs are fed by water pushed upward through joints from the underlying Great Artesian Basin aquifer. The aquifer is reputed to be the world’s largest, underlying 20 percent of the continent. Because of the pressure within the aquifer, the water rises naturally toward the surface, although the continued pumping of groundwater is rapidly drawing down this precious resource.

The Oodnadatta Track also passes alongside the salty shores of Lake Eyre. At 12 meters below sea level, it is the sump for one of the largest interior-draining basins in the world. Most of its basin, which spans one-sixth of the continent, is desert, receiving just 125 to 250 millimeters of rainfall per year — on par with Phoenix, Ariz.

At the tiny town of Oodnadatta, once a major service center for the telegraph and the railway, the track branches. We chose the route through the Painted Desert, a colorful collection of rounded, easily eroded badlands reminiscent of Arizona’s identically named feature. One of our most memorable nights had us camping near these hills, listening to the plaintive wails of wild dingoes and gazing up into the night sky at the brilliant Southern Cross, the Southern Hemisphere’s trademark constellation.

Aboriginal people have inhabited the area near Uluru (bottom) for more than 40,000 years as revealed by the abundant rock art (top) on and near the monolith. Credit: top: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott; bottom: ©Shutterstock.com/Stanislav Fosenbauer.

Our kids were especially excited to see Uluru (also known as Ayers Rock), one of the world’s largest monoliths, whose iconic red, upended sandstone beds seem to rise out of nowhere from the surrounding parched, flat plains of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park (also a UNESCO World Heritage Site). The rock appears ablaze in the light of the setting sun, and watching Uluru’s changing colors as the sun slowly sank below the horizon was a highlight of the trip, as was hiking the 10.6-kilometer-long trail around the monolith’s base the next morning, just after sunrise.

In the same park, the series of elongated domes of Kata Tjuta, which are separated by deep gullies carved along joints, forms an equally spectacular landscape. Kata Tjuta’s walls consist of conglomerate, a rock with clasts ranging up to boulder-sized and embedded in a sandy matrix.

Despite their different compositions, Uluru and Kata Tjuta are closely related. Both are erosional remnants of the debris pile shed 600 million years ago from the Petermann Ranges, which were uplifted during the orogeny of the same name and were towering mountains of Himalayan-scale. Kata Tjuta consists of gravel deposited on alluvial fans near the toe of the mountains, whereas Uluru’s sand accumulated farther downstream.

Later, during the Cambrian Period, seas flooded this landscape and deposited more sediment, gradually burying and lithifying the gravels and sand into conglomerate and sandstone. The later Alice Springs Orogeny gently tilted Kata Tjuta and stood the sandstone layers of Uluru on end. Incessant erosion has since lowered the surrounding landscape, re-exposing the resistant rocks of Uluru and Kata-Tjuta, the undisputed icons of the Red Center.

A paved road leads from Uluru to Kings Canyon, a slickrock gorge cut through the 360-million-year-old dune deposits of the Mereenie Sandstone, which looks like it belongs in southern Utah. North of Kings Canyon lies Gosse Bluff, a 20-kilometer-wide ring of Mereenie Sandstone that was upended during a violent comet impact 130 million years ago. Along the kilometer-long path up to a crater vista, sandstone boulders sport numerous shatter cones, the horsetail-shaped fracture patterns that are a calling card of extraterrestrial impact.

The impressive MacDonnell Ranges west of Alice Springs owe their topography to the distinctive Heavitree Quartzite, deposited as sand about 850 million years ago in the Amadeus Basin. The quartzite was tilted and metamorphosed during both the Petermann and Alice Springs orogenies, turning it into an incredibly erosion-resistant rock that today protrudes above the softer layers to either side.

As our kids happily discovered, several cool, shady gorges with delightfully unexpected swimming holes exist where desert washes cross the Heavitree. All these gorges are worthwhile scenic stops, but the geologic highlight is driving to Ellery Creek Big Hole, where you can quickly peruse the entire 6-kilometer-thick Amadeus Basin sedimentary section thanks to faulting during the Alice Springs Orogeny that stood the layers on end.

Amid all this geologic largess, our favorite site was Palm Valley, which can only be accessed by high-clearance vehicles along a very rough road off the paved Larapinta Drive. Here, springs issuing from the porous, 350-million-year-old Hermannsburg Sandstone create a lush oasis populated by red-cabbage palm trees and cycads. The cycads first flourished 250 million years ago in cooler southern climes when Australia lay locked in the Gondwanan supercontinent. After Australia’s separation from Antarctica, these primitive plants survived by adapting and retreating to refuges like the gorgeous Palm Valley.

Whether you hit the road in a “Rent a Bomb” car or a four-wheel-drive vehicle, the vast expanses, unique rocks and unsurpassed adventure to be found in Australia’s Outback are sure to inspire legends in your own family.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.