by Kathrina Szymborski Wednesday, May 30, 2018

Of the roughly 900 waterfalls in central New York and the Finger Lakes region, one of the most impressive is 65-meter-high Taughannock Falls in Taughannock Falls State Park. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Michael Shake

Adam and I splashed through the water to avoid the pricker bushes along the banks of the East Branch Mohawk River. The water was frigid — it was late in the fall. We were hiking about a kilometer from Adam’s family’s cabin in New York’s Finger Lakes region, in search of a cascade spilling from the surrounding hills. Adam promised that the waterfall was just around the next bend, as he’d done already five times that morning. “Wait up!” I yelled as I bent over to pick a rock out of the water. “I found another fossil!”

A Fossil-rich Area

Adam’s grandparents built the cabin in the 1950s as the anticipated scene of frequent family vacations. The family had stopped using it regularly in the 1990s, and now it felt like a museum. An icebox in the corner was plugged into an outlet that no longer drew electricity; a family of mice had built a comfortable nest inside. Light bulbs gathered dust in their sockets, darkened for decades. A faded Time Magazine from 1998 rested on a desk. It was the perfect setting for a rustic weekend.

These relics of human life sit atop stone teeming with relics of a past geologic era. Ocean levels rose during the Late Cambrian and Ordovician periods almost 500 million years ago, submerging upstate New York under a shallow sea. Over the course of the next 100 million years, through the Silurian period, invertebrates like trilobites, bryozoans, corals, crinoids, brachiopods and mollusks thrived. Today, their imprints remain in the shale, limestone, sandstone and dolomite common to the region. The roadsides along U.S. Route 20 and near Portland Point on Cayuga Lake are particularly popular among fossil hunters.

The cabin is within 30 kilometers of Beecher’s Trilobite Bed, where some of the best-preserved trilobites on Earth have been discovered. Hidden there, in layers of shale less than four centimeters thick, are specimens from the Late Ordovician, with intact exoskeletons and soft tissue preserved through pyrite replacement that reveals detailed antennae, legs, muscles and digestive tracts.

Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI

I examined the fossil I’d just discovered in the stream, fingering the shell-shaped impression in the stone before slipping it into the makeshift bag I’d fashioned out of my shirt.

“You’re not going to be able to go far with 50 pounds of rock on your shoulder,” Adam remarked.

Reluctantly, I set my bag of rocks under a bush. He was right; I wanted to explore the river and surrounding hills unencumbered. After another 10 minutes, we spotted the cascade spilling out of the forest, climbed out of the water and began scrambling through the trees, following the cascade’s path. Wild raspberries kept us sated throughout the hike.

The Finger Lakes Region

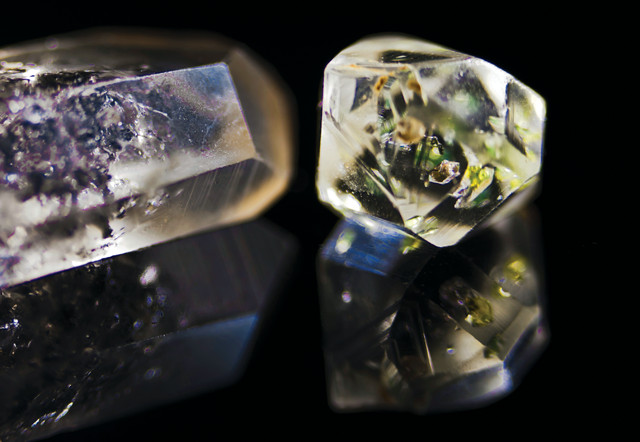

Herkimer diamonds, double-terminated quartz crystals, were first found in dolostone in and around Herkimer County, N.Y., in the late 18th century. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/TexasPete

There are about 900 waterfalls in central New York and the Finger Lakes region, plus countless tiny, unnamed cascades like the one Adam and I found. The most impressive of them tumble into gorges cut by ancient streams, like the 65-meter Taughannock Falls in Taughannock Falls State Park and the 35-meter Lucifer Falls in Robert H. Treman State Park.

The Finger Lakes — originally 11 shallow stream valleys first carved by northward flowing streams — were further gouged and widened over the last two million years by the advance and retreat of ice during the Pleistocene glaciations. Lake Cayuga is the longest of the Finger Lakes, spanning more than 60 kilometers. Just west of Lake Cayuga is the deepest of the lakes, the 188-meter-deep Seneca Lake, the bottom of which lies below sea level. Beneath the lakebeds, the ancient scoured stream valleys are filled with up to 300 meters of glacially scoured sediment. The massive outflow of glacial sediment deposited when the ice sheets retreated also formed more than 10,000 low, rounded hills, called drumlins, in the lakes region. The most famous drumlin is Hill Cumorah, on Route 21 in Manchester, N.Y., where Joseph Smith Jr. supposedly found gold plates bearing the message that became the Book of Mormon. In Chimney Bluffs State Park, wind, rain, snow, and waves have eroded drumlins into dramatic, sharpened crags. These cliffs are still eroding at a rate of up to 1.5 meters per year.

Anorthosite is an intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of plagioclase feldspar. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Arpad Benedek

Visitors to the region would be hard-pressed to run out of activities. In Mendon Ponds Park just outside Rochester, N.Y., which has been named a National Park Service National Natural Landmark for its geological uniqueness, visitors can see a kettle hole lake known as Devil’s Bathtub. The lake formed when a block of ice that calved from a retreating glacier was buried by glacial outwash debris and later melted — leaving behind a hollow pit. It is one of only 11 known meromictic, or unmixed, lakes in the country. At the Herkimer Diamond Mines, visitors take to the mines in search of the six-sided, doubly terminated quartz crystals known as Herkimer Diamonds. The area also offers spectacular bird watching and wine tasting at the many Finger Lakes vineyards and wineries.

The Adirondacks

Adam and I grew up in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., a quaint town in the foothills. He was my older brother’s best friend — an infuriating know-it-all, but quite an asset to your Capture the Flag team.

Our families took us hiking in the Adirondacks’ high peaks on the weekends. The Adirondacks aren’t particularly tall — Mount Marcy, the tallest of the 46 high peaks, reaches only 1,629 meters. Nor is the range very old. It is the result of an uplift that began 5 million to 10 million years ago and continues today, at a rate of 2 to 3 millimeters per year. But the rocks that make up the Adirondacks are about a billion years old, earning them the tag “new mountains from old rocks.”

The Adirondack Mountains lie within Adirondack Park, a 2.5-million-hectare protected area that contains thousands of streams, brooks and lakes, including Saranac Lake. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/James Lusk

The Adirondacks are the only mountains in the Eastern United States that are not geologically related to the Appalachians. Instead, they are part of the Canadian Shield. The rocks in the region are mostly metamorphic, formed under great heat and pressure at depths of up to 30 kilometers in Earth’s crust. Much of the rock is anorthosite; anorthosites are so prominent that State Route 3 through the northern Adirondacks is known to some geologists as the Anorthosite Highway.

Battlefields and Saratoga Springs Environs

Adam and I entered adulthood with a strong connection to the outdoors. On visits home to see our families, we continued the exploring we loved as kids. Saratoga Springs and its environs can keep any outdoors enthusiast busy — especially one with an interest in geology.

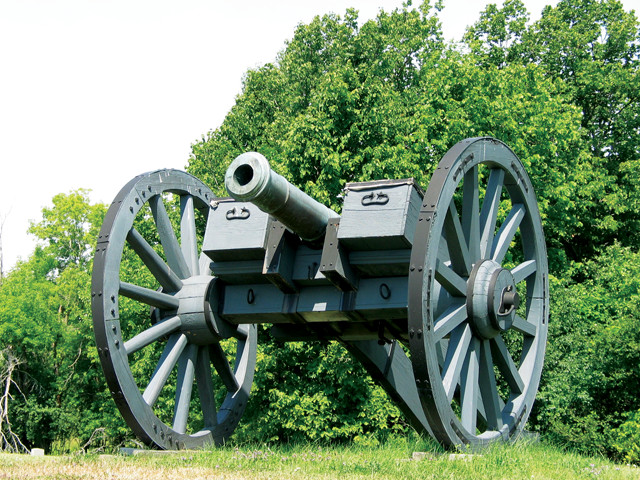

One of our favorite sites was Saratoga National Historical Park. The park is the scene of a crucial American victory over the British during the Revolutionary War. (It was the Americans’ success in the Battles of Saratoga, which took place on Sept. 19 and Oct. 7, 1777, that convinced King Louis XVI of France to join against the British.)

The Saratoga National Historical Park preserves the site of the Battles of Saratoga, the colonists' first significant military victory in the Revolutionary War. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Bradley Gallup

Near the battlefield, Stark’s Knob — the remnant of a pillow basalt — juts out from the grasses and low-lying bushes. The knob was extruded in a shallow back-arc sea about 450 million years ago when a volcanic island arc collided with ancient North America during the Taconic orogeny, the first of the three Appalachian mountain-building episodes. More recently, it was named for General John Stark, who blocked northern passage of British forces by stationing his troops between the knob and the nearby Hudson River. The knob’s summit affords sweeping views of Vermont’s Green Mountains and the Hudson River (as well as any approaching armies).

Sometimes we visited the Petrified Sea Gardens, an enchanting bed of 500-million-old stromatolites in a Cambrian rock layer. We hiked to an old graphite mine and factory near Lake Desolation that had been reclaimed by nature; its crumbling walls offered a climbing challenge to the brave (and probably stupid) among us. We walked the trails along the limestone cliffs in Thacher State Park, taking in views of Albany, the Hudson-Mohawk valleys, and the Adirondack and Green mountains. And, we organized games of Capture the Flag in my parents’ backyard amid old oak trees and glacial erratics, stalking each other’s flags along Putnam Brook until well past sundown.

Mineral Springs

Further downstream, Putnam Brook joins with Slade Creek, which feeds into Geyser Creek in Saratoga Spa State Park. The park is renowned for its mineral springs; there are four along the 1.5-kilometer-long Geyser Creek Trail alone. Dome-shaped mineral tufa deposits swell from the bases of several springs, including Island Spouter and Orenda Spring.

Saratoga Springs boasts 17 naturally carbonated mineral springs scattered throughout the city. The springs gush forth through fissures in the 105-kilometer Saratoga Fault, whose trace is visible in downtown Saratoga Springs. Some springs are housed in fancy pavilions; others are nothing more than a trickle in a rock face. Most are potable, and visitors are welcome to sample the waters or to take a dip at one of the city’s two bathhouses. Each spring has its own flavor, ranging from tasteless to tinged with sodium bicarbonate. Many smell strongly of sulfur. Throughout the 19th century, the springs’ rumored healing properties drew wealthy tourists in droves.

While Saratoga Springs vacationers often seek luxury, its natives prefer to relax by roughing it. That’s why Adam and I had chosen to spend a weekend at his family’s neglected cabin, mice and all, as part of a protracted celebration of my graduation from law school.

“It’s just going to be you and Adam?” asked my mother. “Is it … romantic?”

“No, Mom,” I assured her. “He’s like my brother.”

Our sibling dynamic bore out as usual that weekend in the Finger Lakes. We bickered over the best way to build a fire, my impractical rock collection, and international law and politics. I didn’t know that it was the last time I would see him alive.

Later that year, Adam graduated from business school and went to work for a helicopter tour company in Alaska while gearing up for a stint in the Peace Corps in Africa. On June 11, 2011, he went for a hike near Herbert Glacier and didn’t return. Rescuers found his body on a rock face near the trail the next day. He’d lost his footing and tumbled down an escarpment.

At the time of his death, we were gripped in a heated email exchange about recent elections in Uganda. I had an email draft saved that I was sure would gut his arguments. I just needed a little more time with it. When I miss him, I think of that evening bickering by the fire outside his family’s cabin after a day of collecting fossils. I allow myself to be pulled back into our arguments, and my heartbeat quickens as I recall the unfinished discussions. In those moments, he’s still here, waiting for my scathing email, already anticipating my points and planning his rejoinder. But then I remember: He’s just off adventuring.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.