by Mary Caperton Morton Thursday, January 29, 2015

“Where warm waters halt… where warm waters halt… where warm waters halt.” For two summers, I’ve been exploring the Rocky Mountains with those words on my mind. Why those four words in particular? Because I believe they lead to a modern-day treasure chest.

In 2010, Forrest Fenn, a retired antiquities dealer based in Santa Fe, N.M., set about creating his own legend: He bought an antique bronze chest and filled it with valuables and artifacts including gold dust, coins and nuggets, Chinese jade carvings, a 17th-century gold-and-emerald ring, an ancient turquoise bracelet — together worth between $1 million and $2 million — and then lugged all 19 kilograms of it to a mysterious hiding place somewhere “in the Rocky Mountains north of Santa Fe.” He then released a poem containing nine clues as to the treasure’s whereabouts. More than four years later, nobody has yet found Fenn’s treasure, and he maintains that if it goes undiscovered, the chest will stay safely in place for hundreds of years.

The Fenn treasure has been valued between million and $2 million and the chest itself — a 12th-century Roman lockbox made of sculpted bronze — has been said to be worth about $35,000. Credit: Forrest Fenn.

Thousands of people from all walks of life have gone searching for Fenn’s treasure in New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming and Montana (Fenn has eliminated Utah and Idaho). When I heard about the treasure, I couldn’t help thinking about it from a geologist’s point of view: The poem implies that the treasure is hidden near water, but the courses of waterways can change drastically over time, even from season to season, let alone over centuries. And as someone interested in archaeology and paleontology, I’m well aware that if you find something interesting on public land, it’s not always “finders, keepers.” I was intrigued. Could I put my background in geology and my hiker’s knowledge of landscapes to work searching for a treasure chest?

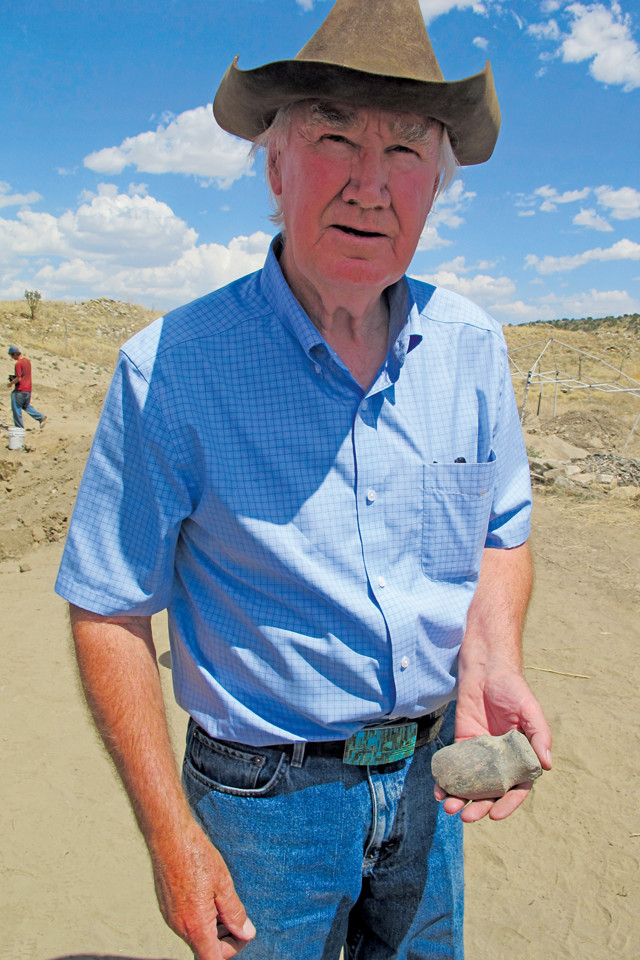

In the 1980s, Fenn, an amateur archaeologist, purchased the San Lazaro Pueblo, a prehistoric pueblo site settled about 700 years ago by the Tano tribe. Fenn has spent the last several decades excavating the pueblo, which grew to more than 2,000 rooms before being abandoned roughly 300 years ago. Credit: Forrest Fenn.

In some circles, Fenn cuts a notorious figure. As a private collector of Native American artifacts and a highly successful art and antiquities dealer, he has raised the ire of some scholars, curators and archaeologists over the years. But he’s also a local legend in Santa Fe’s art world, a self-proclaimed maverick, whose memoirs detail a lifetime of adventures, from lassoing a wild bison to flying fighter jets in Vietnam and traveling all over the world — Indiana Jones-style — in search of interesting artifacts.

Fenn began collecting at age 9, when he found his first arrowhead in a farmer’s field in Texas. Seven decades later, he still has that arrowhead and calls it his most treasured object in his vast, diverse collection of Native American artifacts, which includes dolls, ceremonial shields and pottery, among other items.

After that inspirational arrowhead, Fenn’s next-most-prized possessions may be Sitting Bull’s peace pipe or, on a larger scale, the San Lazaro Pueblo: In the mid-1980s, Fenn bought 65 hectares in the Galisteo Basin south of Santa Fe that included a prehistoric pueblo site known as San Lazaro. Settled about 700 years ago by the Tano tribe, the pueblo grew to more than 2,000 rooms before being abandoned roughly 300 years ago. Fenn has personally been excavating the site for more than two decades, turning up relics such as ancient gaming pieces, beaded jewelry and human effigies, including a rare plaster mask.

“Fenn has a wonderful collection of Plains and Southwestern material that he has acquired over the last 40 years,” says Clinton Nagy, curator of the Splendid Heritage website, which catalogs private collections such as Fenn’s for educational purposes. “In my opinion, he has done a lot of good in preserving native culture.”

Fenn’s impressive resume and reputation seem to assure seekers that his treasure is no hoax. “I met Forrest many years ago when I lived in Santa Fe and worked in an Indian artifact gallery. He has an impeccable reputation in that world,” says Katya Luce, an avid treasure seeker who moved from Maui back to New Mexico to look for Fenn’s treasure. “Knowing Forrest, I never doubted for a moment whether the treasure was real.”

Fenn estimates that at least 30,000 people have sought his treasure. Chief among them is Dal Neitzel, seen below searching a stream, who runs one of the most active Forrest Fenn treasure blogs. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

Fenn hid the treasure in 2010 after a cancer scare. “I became sick and thought I was on my way out and I wanted to inspire others to join in the thrill of the chase,” he says. The decision was not spur of the moment, however. His hiding location was a place he’d been visiting for many years. “I knew exactly where to hide the chest so it would be difficult to find but not impossible,” Fenn wrote in his 2011 memoir, “The Thrill of the Chase.” Fenn says he worked on the poem for a long time too, “changing and rearranging. Each word is crafted in its place. No part of it was not looked at from every angle.”

Fenn’s poem contains nine clues that, he says, if followed correctly, will lead to his treasure chest. The poem is short and fairly simple, but contains enough fodder to hide a few potential red herrings. “Forrest is an exceedingly clever fellow. If anybody does ever solve his poem, I’m sure it’ll be full of twists and turns and double meanings,” says Dal Neitzel, who runs one of the most active Forrest Fenn treasure blogs. Fenn suggests that searchers start at the beginning of the poem and follow it linearly. After a few introductory lines, the poem reads: “Begin it where warm waters halt.” In my own experience, flowing water is rarely warm in the mountains, and it never halts. The most obvious interpretations of this clue suggest that it refers to a hot spring, or a dam with a relatively warm lake, although Fenn has said the “treasure is not associated with any manmade structure.”

Fenn is known to enjoy clever wordplay and double meanings. The "blaze" mentioned in the poem may or may not be a trail marker, like this rock etching found along the Rio Grande. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

Another very popular interpretation is that his use of “warm waters” is a nod to the New Mexico State Game and Fish Department’s classification of all streams, lakes and ponds – except those designated as trout waters – as “warm waters.” Fenn is an avid fly fisherman, so the phrase “where warm waters halt” could point to a boundary between warmer gamefish waters and colder trout waters.

“Forrest has said that people are thinking about the warm waters clue too hard,” Luce says. “But it’s a tricky one. What defines warm water? And what does it mean to say waters halt? That’s not really the nature of water.”

After the cryptic initial hint, the clues get a little more straightforward: “take it in the canyon down, not far but too far to walk,” which seems to imply a direction and that there is some distance to travel. But the next reference is a head-scratcher: “put in below the home of Brown.” “Put in” is a boating term so “brown” could reference a fishing hole for brown trout. Some people think it references the brown grizzly bears of Yellowstone. Still others scour maps and historical records for any place or person named Brown.

The next lines seem to hint at a difficult journey: “from there it’s no place for the meek, the end is ever drawing nigh; there’ll be no paddle up your creek, just heavy loads and water high.” This again seems to refer to a waterway, perhaps one that requires a boat and a portage. But it might be misleading to think of Fenn’s treasure as necessarily being hidden in some remote, difficult to reach place. After all, an ailing 80-year-old man carried it to the location by himself. He did it in two trips in one afternoon, he has said, carrying the chest in first and then the contents.

“The chest is not in a dangerous place,” he has said. “It’s somewhere you could take your kids.” But he has also said it’s not somewhere that anybody is likely to stumble upon it accidentally. “The person who finds the treasure will have studied the poem over and over, and thought and analyzed and moved with confidence. Nothing about it will be accidental,” Fenn says.

Phillip Mason (left) moved to Taos from northern Nevada two years ago to look for Fenn's treasure. Some treasure seekers have interpreted "home of Brown" in the poem to refer to trout waters, as Fenn is an avid fisherman. Credit: both: Mary Caperton Morton.

“The Rocky Mountains north of Santa Fe” is a lot of ground to cover. So, I, like many searchers, chose to start in Fenn’s backyard in New Mexico. For my first expedition, in May 2013, a friend and I headed to Questa, about 30 kilometers north of Taos. Armed with topographic maps and old Bureau of Land Management (BLM) mining charts, we searched all around the Red River fish hatchery (a potential “home of Brown,” we thought), convinced we’d find it tucked inside the entrance of one of the many old mines in the area. But the only treasure we found was an intact coyote skull.

Then we moved south to the John Dunn Bridge, which spans the Rio Grande near Arroyo Hondo. The well-known, oft-frequented Manby Hot Springs bubbles just downstream from the bridge. We weren’t the only people on the hunt there; across the river we spotted three hikers using a metal detector to scan the basalt rubble that lines the Rio Grande Gorge.

We went home empty-handed and a little overwhelmed by the potential search area. Even if we were in the right place, the Rio Grande Gorge is immense, with countless pockets in the basalt walls for stashing a small bronze box. Even if we were in the right place, the chest could be anywhere in that landscape. “When I first started searching, I thought I knew for sure where it was, but the more I look, the further it seems I am from it,” Luce says.

The author and a friend searched near Manby Hot Springs in the Rio Grande Gorge near Taos, N.M. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

It was time to consult a professional: Phillip Mason moved to Taos from northern Nevada two years ago to look for Fenn’s treasure. Mason’s no amateur treasure seeker: He made a living mining gold in Nevada, and he has been systematically canvassing northern New Mexico for Fenn’s chest.

I told Mason I was working on a story about the Fenn treasure and he agreed to take me along on an expedition. When we met in downtown Taos, he asked, quite seriously: “If we find that chest today, how are we going to split it?” I told him he could have everything, but I wanted the turquoise bracelet, for which Fenn has offered a bounty (see sidebar). “You’ve done your homework,” Mason said approvingly.

Mason believes the quest begins at Wheeler Peak, the highest mountain in New Mexico. “Forrest mentions a Taos Mountain in his book several times,” Mason says. “There’s no Taos Mountain on the map, but that’s one of the nicknames for Wheeler.” So we headed up the road to the Taos ski resort and parked at a few pullouts along the road to bushwhack upslope to some interesting landmarks that Mason thinks might line up with some of the clues.

Some treasure hunters believe the quest begins at Wheeler Peak, the highest mountain in New Mexico. Taos Ski Valley is in the distance. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

After two seasons of searching with no luck, Mason has turned to a new source for inspiration: kids. “Forrest has a very creative, childlike mind, and I mean that in the best way,” he says. “I’ve been asking kids for their interpretation of the clues and I’ve been getting some very interesting answers. I don’t know if I’m any closer, but it sure is keeping the search fresh in my mind.”

According to Fenn, the treasure could be hidden in one of three places: “public land, tribal land or private property. It is not my intention to make a statement that will narrow the search area.” Most tribal lands are off-limits to outsiders, making places such as the backcountry wilderness around Blue Lake, held sacred by the Taos Pueblo in northern New Mexico, an unlikely place for a treasure hunt.

Private land is a possibility, if it were unposted and accessed through public land. But Fenn is not known to own land other than San Lazaro, and he maintains that he hasn’t shared the location of the chest with anybody else, making it unlikely that he got permission from a private landowner to stash his treasure on their property. So that leaves public land as the most likely category.

The United States has more than 2 million square kilometers of public land managed by BLM, the National Park Service and the Forest Service. Most public land is open for recreational use, but the types of recreation permitted vary widely. In some places, like the BLM’s Wild Rivers Recreation Area in northern New Mexico, collecting rocks on the surface is permitted, while in national parks, toting off a piece of obsidian can result in a hefty fine.

One of the main legal distinctions hinges on whether the chest is buried; Fenn has hinted that it’s not. “On BLM land in New Mexico, as long as it’s not buried, if somebody found the chest, they would be permitted to take it,” says Allison Sandoval, a BLM representative in Santa Fe. Sandoval is quick to point out that artifacts such as arrowheads and pottery found on BLM land are not “finders, keepers,” however. “Fenn’s treasure isn’t an artifact. It’s kind of a unique situation, but as long as there’s no degradation of the land involved in collecting it, it’s fair game.”

Yellowstone National Park is a hot bed for searchers due to Fenn’s boyhood adventures in the park and around Hebgen Lake and West Yellowstone, but the National Park Service has an entirely different stance on collecting.

“Treasure hunting is not illegal in Yellowstone, but there’s a whole host of regulations that govern the preservation and use of national parks,” says Tim Reid, chief ranger at Yellowstone. “Metal detectors are illegal, digging is illegal, and you can’t remove any natural or cultural feature from the park.” If somebody were to find the Fenn treasure within the boundaries of Yellowstone, or any national park, it would be considered abandoned property, Reid says. “It’s not ‘finders, keepers.’ You would have to turn it in and go through a governmental procedure to lay claim to it.”

The treasure could be on public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management, the National Park Service or the Forest Service, which raises questions about its ownership if found. Credit: Mary Caperton Morton.

Some of the Fenn treasure hunters have run afoul of the rules in Yellowstone, and a handful have even gotten themselves banned from the park, Reid says. “People who choose to believe the treasure exists typically seem to be unprepared for wilderness conditions. We’ve had several search and rescues, and a host of violations; people have been cited and some have been arrested,” Reid says. “Some are lucky not to have been seriously injured or killed.”

Land-use regulations may seem to narrow the search field, but as Neitzel points out, Fenn hid the treasure without anybody seeing him do it, so somebody should be able to get the chest without getting caught by authorities. “The poem says ‘take the chest and go in peace,’ which may imply that a searcher shouldn’t make a fuss about where it was found,” Mason says.

“Forrest has said that there was nowhere he could have hid the treasure that would not involve some potential complications,” Mason says. “Maybe the answer is to take it clear of its hiding place and keep quiet about it.”

The Forest Service does not agree with that strategy, however. “If somebody were to find the chest and not report it, that’s theft of government property,” says Mike Bremer, a forest service archaeologist with the Santa Fe National Forest. “Frankly, I think this whole treasure hunt is a nuisance and a potential danger to the vast reserves of cultural artifacts and archaeology in Santa Fe National Forest.”

In the past four years, Fenn has issued a few additional hints about the location of his treasure, but he’s not giving it away: The chest is above 1,500 meters of elevation; it’s not associated with any manmade structure; and it’s not buried in a graveyard.

Curious about the long-term fate of both the chest and the quest, I asked Fenn whether the clues in the poem will also withstand the test of time. “I am guessing the clues will stand for centuries. That was one of my basic premises, but the treasure chest will fall victim to geological phenomena just like everything else. Who can predict earthquakes, floods, mudslides, fires, tornadoes and other factors?” Fenn says.

Based on the number of emails he’s received, Fenn estimates about 30,000 people are looking for the chest, but, as far as he knows, nobody has found it yet. Asked whether he hopes the chest is found within his lifetime, Fenn says, “I am ambivalent. When I hid the treasure, its fate left my hands. Now it is for the ages.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.